Chesapeake Hospital,

August 26, 1864.

Dear Father:—

This letter of yours has been to Hilton Head I suppose, and then to the Army of the Potomac, and next day, by the kindness of Captain Dickey, to me here. He is a captain, that same Dickey. His good qualities wear like steel.

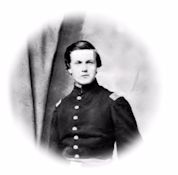

Twenty days old this letter is. In that time you must have received several from me, not all addressed to you, but to the family, some of them, papers for the boys, and one I sent to Mother with a little note about the picture. I don’t believe they can all have miscarried. Well, one thing is certain, it won’t take a month for letters to pass now, and I comfort myself by thinking that you will be reading this about Monday or Tuesday next, and by and by all this arriere will be straightened up.

After hearing what you have had to occupy you lately, I recall my impatient remarks about your want of interest, etc. Indeed, they were not leveled at you. Though you give every other reason I know that you do not like to write letters. You sit down to it as to a job that must be done and I do not expect you to write often.

I had an idea that I had a sister out there who (if she follows the track of young persons of her sex) must be quite a young lady by this time. Young ladies are supposed to wield a ready pen, to be familiar with the state of the family and to love to gossip about it. They generally have time enough, but despite all my ideas, hypotheses, etc., I find a married sister with a husband to take care of, a house to sweep, the stockings to darn, and the slight care of a dairy—I find her writing to me every week, while this young lady finds time about once in six months. E. is a “brick.” He writes as often as he can, and, though I haven’t received any from him of very late date, I lay it to the bags. I hope soon to hear from him that he is back in the hardware in Toledo. “What would you think,” he says in his last, “if I should get as large a salary as Father’s?” He got a stomach-full of the army in one hundred days. If he goes again, it will be with a strong impression that he can’t help it. I wrote to him, directing to Brooklyn, thinking of course he would be at home a few days, or at least you would know where he is. He said Mr. P. was very anxious he should come back to his store, but he himself did not seem very anxious to accept so advantageous a situation.

I am very sorry to hear of your trouble about the house; however I suppose it is all over now. I hope so at least. I should think with such a scarcity of dwellings some Yankee would be putting up houses to rent. I had very much such a time as yours approached, just before coming here. Getting sick in camp, I was left behind unable to march. “In camp” in the Army of the Potomac now is a pleasant fiction, meaning any place a regiment bivouacs on over night. So they moved away and left me, our efficient medical staff making no provision for sick. Two days I stayed there, living on the kindness of some sick men from Maine. Then our adjutant came and mounted me on his own horse, like a good Samaritan, and took me to the corps hospital. The medical director wanted to see my papers. I must be committed like a pauper to the poorhouse. I was “liable to be arrested” for absence from my regiment without authority. You may understand it was trying to my temper to be called a skulk the first time I came near a hospital in more than three years. I turned away from him in disgust and lay down under a tree on the bank of the river. The adjutant left me there and said he would not rest till he had got the order sending me to the hospital. So there I lay and my thoughts were not pleasant. By and by I heard a rattle of musketry and knew my regiment was “in.” Then it blew and began to rain. I curled myself up in my gum blanket and felt miserable enough, sick, weak, and no place to shelter my head.

The next afternoon a doctor came and asked me who I was and how I came there. I told him my story and he had the kindness to be shocked—”didn’t see into it—anyone could see I was sick—didn’t need any papers” and he immediately wrote the papers I enclose and sent me on the boat. I feel very weak, have only been out doors once. If it were any use I would apply for leave of absence as soon as I am able to travel, but it is not. I would be ordered to Annapolis and put on court-martial or some other light duty. It is next to impossible to get leave of absence.

The Eighth has redeemed any reputation it lost at Olustee. It was the Eighth before which “eighty-two dead rebels were counted after the battle,” according to Birney’s dispatch.