MAY 23D.—Our regiment lay in the rifle pits to-day, watching the enemy. For hours we were unable to see the motion of a man or beast on their side, all was so exceedingly quiet throughout the day. After dark we were relieved, and as we returned to the camp the enemy got range of us, and for a few minutes their bullets flew about us quite freely. However, we bent our heads as low as we could and double-quicked to quarters. One shot flew very close to my head, and I could distinctly recognize the familiar zip and whiz of quite a number of others at a safer distance. The rebels seemed to fire without any definite direction. If our sharpshooters were not on the alert, the rebels could peep over their works and take good aim; but as they were so closely watched they had to be content with random shooting.

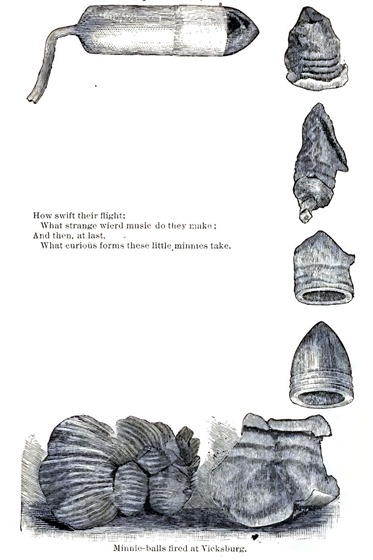

If this siege is to last a month there will be a whole army of trained sharpshooters, for the practice we are getting is making us skilled marksmen. I have gathered quite a collection of balls, which I mean to send home as relics of the siege. They are in a variety of shapes, and were a thousand brought together there could not be found two alike. I have picked up some that fell at my feet—others were taken from trees. I am the only known collector of such souvenirs, and have many odd and rare specimens. Rebel bullets are very common about here now—too much so to be valuable; and as a general thing the boys are quite willing to let them lie where they drop. I think, however, should I survive, I would like to look at them again in after years.

If this siege is to last a month there will be a whole army of trained sharpshooters, for the practice we are getting is making us skilled marksmen. I have gathered quite a collection of balls, which I mean to send home as relics of the siege. They are in a variety of shapes, and were a thousand brought together there could not be found two alike. I have picked up some that fell at my feet—others were taken from trees. I am the only known collector of such souvenirs, and have many odd and rare specimens. Rebel bullets are very common about here now—too much so to be valuable; and as a general thing the boys are quite willing to let them lie where they drop. I think, however, should I survive, I would like to look at them again in after years.

Shovel and pick are more in use to-day, which seems to be a sign that digging is to take the place of charging at the enemy. We think Grant’s head is level, anyhow. The weather is getting hotter, and I fear sickness; and water is growing scarce, which is very annoying. If we can but keep well, the future has no fears for us.