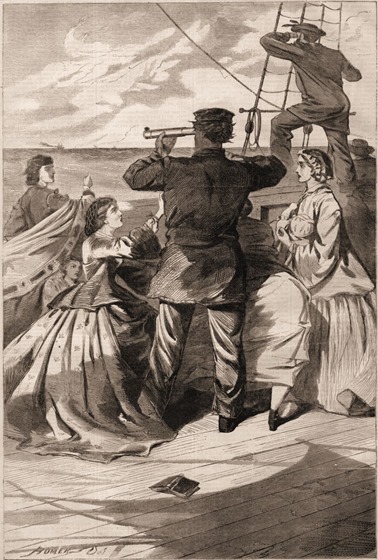

The Approach of the British Pirate “Alabama.”

______

IT is not to be disguised that our relations with Great Britain have reached a most critical pass. The speeches of the Solicitor-General of England and of Lord Palmerston, in Parliament, on 27th March, indicate a determined purpose on the part of the British Government to persevere in the work of fitting out piratical vessels in British ports to prey upon our merchant navy, It was well shown by Messrs. Forster, Baring, and others, that the equipment of the Florida and Alabama was in violation of the Foreign Enlistment Act; and that other similar vessels—some say eighteen, others fourteen—are being constructed for the rebels at Liverpool and other British ports, without let or hindrance by the Government, and will soon be at sea, manned by British sailors, armed with British guns, and as thoroughly British in every respect as the Warrior herself. The only answer to these cogent facts was some legal quips and quibbles in the Nisi Prius style by the Solicitor, and a sneer from Lord Palmerston about “the Americans always picking a quarrel with England whenever they got into trouble.”

Passing over the insolence of the latter speaker, who has been well said to represent the black-leg element in the British Cabinet, and the cheap erudition of the lawyer who was hired to defend the Government, the fact remains that we are practically at war with Great Britain without the power of reprisals. Every British dock-yard is now engaged in building steamers to capture and burn our merchantmen, to run our blockade, and to bombard our defenseless sea-board cities. The evidence points irresistibly to the conclusion that all the authorities and men in stations of influence in England are in the conspiracy against us. Lord Palmerston considers our complaints of the destruction of thirty odd American vessels by the British cruiser Alabama mere indications of our wish to pick a quarrel with England; Lord Russell sees no ground for arresting the Alabama until he has been assured she has got safely to sea, when he issues his tardy warrant; Member of Parliament Laird laughs—and the House of Commons re-echoes the laugh—at the objections which are made to his supplying the rebels with a navy; the Commissioners of Customs, with their ears stuffed with cotton and their pockets with the produce of Confederate bonds, are ready to swear off the most obvious Confederate steamer as a harmless craft intended for the Emperor of China; and the merchants, ship-builders, and newspapers of England all claim the right of furnishing the rebels with a navy, and denounce us furiously for objecting to their conduct.

These events have very naturally aroused a general and intense hostility to England among all classes in this country. There has never been a time when hatred of the English was so deep or so wide-spread as it is at present. There has never been a period at which war with England could have been more generally welcomed than at present—if we were free to engage in a foreign war.

Yet we do not believe that war is imminent. We can not afford the luxury. The struggle in which we are engaged taxes all our resources, and to carry it safely through to a successful issue will require our undivided energies. For this reason we do not anticipate that our Government will declare war against England— though it has ample ground for doing so; or will even declare an embargo, or seize British property to recompense our ship-owners for the losses they are suffering through the piratical acts of British vessels.

Our cue just now is to suffer every thing from foreigners for the sake of concentrating our whole strength on the suppression of the rebellion. When this is done, we shall have time to devote to our foreign enemies.

So soon as the restoration of the Union has been achieved, we look to see energetic measures adopted by our Government for the settlement of accounts with England. We expect to see every man who has lost a dollar by the depredations of the Alabama paid in full, with interest, by the British Government. The amount can always be collected in the port of New York. Half a dozen British steamers and a score of British ships seized and sold at auction by the United States Marshal would go far to make a balance. And when England next goes to war, let her look out for retaliation. Though her antagonist be only some Hottentot chief, the ocean shall bristle with American cruisers bearing his flag, and England may rely upon it, that for every peaceful American trader that has been burned during this war by British pirates, ten British vessels will then be destroyed. The next war in which England engages will be the end of her foreign commerce. We mistake our countrymen greatly, if, at the end of twelve months, they leave a ship bearing the British flag afloat in any sea from the German Ocean to Behring’s Straits.

But the watch-word now must be—Patience!

(Harper’s Weekly, April 25, 1863)