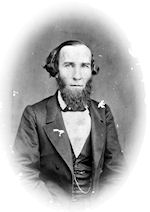

April 2d.—Governor Manning came to breakfast at our table. The others had breakfasted hours before. I looked at him in amazement, as he was in full dress, ready for a ball, swallow-tail and all, and at that hour. “What is the matter with you?” “Nothing, I am not mad, most noble madam. I am only going to the photographer. My wife wants me taken thus.” He insisted on my going, too, and we captured Mr. Chesnut and Governor Means.¹ The latter presented me with a book, a photo-book, in which I am to pillory all the celebrities.

Doctor Gibbes says the Convention is in a snarl. It was called as a Secession Convention. A secession of places seems to be what it calls for first of all. It has not stretched its eyes out to the Yankees yet; it has them turned inward; introspection is its occupation still.

Last night, as I turned down the gas, I said to myself: “Certainly this has been one of the pleasantest days of my life.” I can only give the skeleton of it, so many pleasant people, so much good talk, for, after all, it was talk, talk, talk à la Caroline du Sud. And yet the day began rather dismally. Mrs. Capers and Mrs. Tom Middleton came for me and we drove to Magnolia Cemetery. I saw William Taber’s broken column. It was hard to shake off the blues after this graveyard business.

The others were off at a dinner party. I dined tête-à-tête with Langdon Cheves, so quiet, so intelligent, so very sensible withal. There never was a pleasanter person, or a better man than he. While we were at table, Judge Whitner, Tom Frost, and Isaac Hayne came. They broke up our deeply interesting conversation, for I was hearing what an honest and brave man feared for his country, and then the Rutledges dislodged the newcomers and bore me off to drive on the Battery. On the staircase met Mrs. Izard, who came for the same purpose. On the Battery Governor Adams² stopped us. He had heard of my saying he looked like Marshal Pelissier, and he came to say that at last I had made a personal remark which pleased him, for once in my life. When we came home Mrs. Isaac Hayne and Chancellor Carroll called to ask us to join their excursion to the Island Forts to-morrow. With them was William Haskell. Last summer at the White Sulphur he was a pale, slim student from the university. To-day he is a soldier, stout and robust. A few months in camp, with soldiering in the open air, has worked this wonder. Camping out proves a wholesome life after all. Then came those nice, sweet, fresh, pure-looking Pringle girls. We had a charming topic in common—their clever brother Edward.

A letter from Eliza B., who is in Montgomery: “Mrs. Mallory got a letter from a lady in Washington a few days ago, who said that there had recently been several attempts to be gay in Washington, but they proved dismal failures. The Black Republicans were invited and came, and stared at their entertainers and their new Republican companions, looked unhappy while they said they were enchanted, showed no ill-temper at the hardly stifled grumbling and growling of our friends, who thus found themselves condemned to meet their despised enemy.”

I had a letter from the Gwinns to-day. They say Washington offers a perfect realization of Goldsmith’s Deserted Village.

Celebrated my 38th birthday, but I am too old now to dwell in public on that unimportant anniversary. A long, dusty day ahead on those windy islands; never for me, so I was up early to write a note of excuse to Chancellor Carroll. My husband went. I hope Anderson will not pay them the compliment of a salute with shotted guns, as they pass Fort Sumter, as pass they must.

Here I am interrupted by an exquisite bouquet from the Rutledges. Are there such roses anywhere else in the world? Now a loud banging at my door. I get up in a pet and throw it wide open. “Oh!” said John Manning, standing there, smiling radiantly; “pray excuse the noise I made. I mistook the number; I thought it was Rice’s room; that is my excuse. Now that I am here, come, go with us to Quinby’s. Everybody will be there who are not at the Island. To be photographed is the rage just now.”

We had a nice open carriage, and we made a number of calls, Mrs. Izard, the Pringles, and the Tradd Street Rutledges, the handsome ex-Governor doing the honors gallantly. He had ordered dinner at six, and we dined tête-à-tête. If he should prove as great a captain in ordering his line of battle as he is in ordering a dinner, it will be as well for the country as it was for me to-day.

Fortunately for the men, the beautiful Mrs. Joe Heyward sits at the next table, so they take her beauty as one of the goods the gods provide. And it helps to make life pleasant with English grouse and venison from the West. Not to speak of the salmon from the lakes which began the feast. They have me to listen, an appreciative audience, while they talk, and Mrs. Joe Heyward to look at.

Beauregard³ called. He is the hero of the hour. That is, he is believed to be capable of great things. A hero worshiper was struck dumb because I said: “So far, he has only been a captain of artillery, or engineers, or something.” I did not see him. Mrs. Wigfall did and reproached my laziness in not coming out.

Last Sunday at church beheld one of the peculiar local sights, old negro maumas going up to the communion, in their white turbans and kneeling devoutly around the chancel rail.

The morning papers say Mr. Chesnut made the best shot on the Island at target practice. No war yet, thank God. Likewise they tell me Mr. Chesnut has made a capital speech in the Convention.

Not one word of what is going on now. “Out of the fulness of the heart the mouth speaketh,” says the Psalmist. Not so here. Our hearts are in doleful dumps, but we are as gay, as madly jolly, as sailors who break into the strong-room when the ship is going down. At first in our great agony we were out alone. We longed for some of our big brothers to come out and help us. Well, they are out, too, and now it is Fort Sumter and that ill-advised Anderson. There stands Fort Sumter, en evidence, and thereby hangs peace or war.

Wigfall† says before he left Washington, Pickens, our Governor, and Trescott were openly against secession; Trescott does not pretend to like it now. He grumbles all the time, but Governor Pickens is fire-eater down to the ground. “At the White House Mrs. Davis wore a badge. Jeff Davis is no seceder,” says Mrs. Wigfall.

Captain Ingraham comments in his rapid way, words tumbling over each other out of his mouth: “Now, Charlotte Wigfall meant that as a fling at those people. I think better of men who stop to think; it is too rash to rush on as some do.” “And so,” adds Mrs. Wigfall, “the eleventh-hour men are rewarded; the half-hearted are traitors in this row.”

____

¹ John Hugh Means was elected Governor of South Carolina in 1850, and had long been an advocate of secession. He was a delegate to the Convention of 1860 and affixed his name to the Ordinance of Secession. He was killed at the second battle of Bull Run in August, 1862.

² James H. Adams was a graduate of Yale, who in 1832 strongly opposed Nullification, and in 1855 was elected Governor of South Carolina.

³ Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard was born in New Orleans in 1818, and graduated from West Point in the class of 1838. He served in the war with Mexico; had been superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point a few days only, when in February, 1861, he resigned his commission in the Army of the United States and offered his services to the Confederacy. (Actually, according to correspondence between Senator Slidell and President Buchanan, Beauregard was relieved of command.)

† Louis Trezevant Wigfall was a native of South Carolina, but removed to Texas after being admitted to the bar, and from that State was elected United States Senator, becoming an uncompromising defender of the South on the slave question. After the war he lived in England, but in 1873 settled in Baltimore. He had a wide Southern reputation as a forcible and impassioned speaker.