On the 1st of April, while at my dinner at Willard’s, where I then boarded, Mr. Nicolay, the private secretary of the President, brought to me and laid upon the table a large package from the President. It was between five and six o’clock in the afternoon when I received this package, which I immediately examined and found it contained several papers of a singular character, in the nature of instructions, or orders from the Executive in relation to naval matters, and one in reference to the government of the Navy Department more singular and remarkable than either of the others. This extraordinary document was as follows: —

(Confidential)

Executive Mansion, April 1, 1861.

To the Secretary of the Navy.

Dear Sir: You will issue instructions to Captain Pendergrast, commanding the home squadron, to remain in observation at Vera Cruz — important complications in our foreign relations rendering the presence of an officer of rank there of great importance.

Captain Stringham will be directed to proceed to Pensacola with all possible despatch, and assume command of that portion of the home squadron stationed off Pensacola. He will have confidential instructions to cooperate in every way with the commanders of the land forces of the United States in that neighborhood.

The instructions to the army officers, which are strictly confidential, will be communicated to Captain Stringham after he arrives at Pensacola.

Captain Samuel Barron will relieve Captain Stringham in charge of the Bureau of Detail.

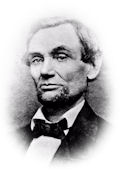

Abraham Lincoln.

P. S. As it is very necessary at this time to have a perfect knowledge of the personal of the navy, and to be able to detail such officers for special purposes as the exigencies of the service may require, I request that you will instruct Captain Barron to proceed and organize the Bureau of Detail in the manner best adapted to meet the wants of the navy, taking cognizance of the discipline of the navy generally, detailing all officers for duty, taking charge of the recruiting of seamen, supervising charges made against officers, and all matters relating to duties which must be best understood by a sea officer. You will please afford Captain Barron any facility for accomplishing this duty, transferring to his department the clerical force heretofore used for the purposes specified. It is to be understood that this officer will act by authority of the Secretary of the Navy, who will exercise such supervision as he may deem necessary.

Abraham Lincoln.

Without a moment’s delay I went to the President with the package in my hand. He was alone in his office and, raising his head from the table at which he was writing, inquired, “What have I done wrong?” I informed him I had received with surprise the package containing his instructions respecting the Navy and the Navy Department, and I desired some explanation. I then called his attention particularly to the foregoing document, which I read to him. This letter was in the handwriting of Captain Meigs of the army, then Quartermaster-General; the postscript in that of David D. Porter, since made Vice-Admiral. The President expressed as much surprise as I felt, that he had sent me such a document. He said Mr. Seward, with two or three young men, had been there through the day on a subject which he (Seward) had in hand, and which he had been some time maturing; that it was Seward’s specialty, to which he, the President, had yielded, but as it involved considerable details, he had left Mr. Seward to prepare the necessary papers. These papers he had signed, many of them without reading, — for he had not time, and if he could not trust the Secretary of State, he knew not whom he could trust. I asked who were associated with Mr. Seward. “No one,” said the President, “but these young men were here as clerks to write down his plans and orders.” Most of the work was done, he said, in the other room. I then asked if he knew the young men. He said one was Captain Meigs, another was a naval officer named Porter.

I informed the President that I was not prepared to trust Captain Barron, who was by this singular proceeding, issued in his name, to be forced into personal and official intimacy with me. He said he knew nothing of Barron except he had a general recollection that there was such an officer in the Navy. The detailing officer of the Department, I said to him, ought to have the implicit confidence of the Secretary, and should be selected by him. This the President assented to most fully. I then told him that Barron, though a pliant gentleman, had not my confidence, and I thought him not entitled to that of the President in these times; that his associations, feelings, and views, so far as I had ascertained them, were with the Secessionists; that he belonged to a clique of exclusives, most of whom were tainted with secession notions; that, though I was not prepared to say he would desert us when the crisis came on, I was apprehensive of it, and while I would treat him kindly, considerately, and hoped he would not prove false like most others of his set, I could not give him the trust which the instructions imposed.

The President reiterated they were not his instructions, though signed by him, that the paper was an improper one, that he wished me to give it no more consideration than I thought proper, to treat it as canceled, or as if it had never been written. He said he remembered that both Seward and Porter had something to say about Barron, as if he was a superior officer, and in some respects, perhaps, out any equal in the Navy, but he certainly never would have assigned him or any other man knowingly the position without consulting me.

Barron was a courtier, of mild and affable manners, a prominent and influential officer, especially influential with the clique which recognized him as a leader. He and D. D. Porter were intimate friends, and both were favorites of Jefferson Davis, Slidell, and other Secessionists, who, I had learned, paid them assiduous attention.

When I took charge of the Navy Department, I found great demoralization and defection among the naval officers. It was difficult to ascertain who among those that lingered about Washington could and who were not to be trusted. Some belonging to the Barron clique had already sent in their resignations. Others, it was well understood, were prepared to do so as soon as a blow was struck. Some were hesitating, undecided what step to take. Barron, Buchanan, Maury, Porter, and Magruder were in Washington, and each and all were, during that unhappy winter, courted and caressed by the Secessionists, who desired to win them to their cause. I was by reliable friends put on my guard as respected each of them. Buchanan, Maury, and Magruder were each holding prominent place and on duty. Barron was familiar with civil and naval matters, was prepared for any service, ready to be called to discharge such duties as are constantly arising in the Department, requiring the talents of an intelligent officer.

Porter had some of the qualities of Barron, with more dash and energy, was less plausible, more audacious, and careless in his statements, but like him was given to intrigues. His associations, as well as Barron’s, during the winter of 1861, had been intimate with the Secessionists. He sought and obtained orders for Coast Survey service in the Pacific, which indicated an intention to avoid active participation in the approaching controversy. That class of officers who at such a time sought duties in the Pacific and on foreign stations were considered, prima facie, as in sympathy with the Secessionists, but yet not prepared to give up their commissions and abandon the Government. No men were more fully aware that a conflict was impending, and that, if hostilities commenced and they were within the call of the Department, they would be required to participate. Hence a disposition to evade an unpleasant dilemma by going away was not misunderstood.

Barron and Porter occupied in the month of March an equivocal position. They were intimate, they were popular, and the eye of the Department was necessarily upon them, as it was, indeed, upon all in the service. In two or three interviews with me, Barron deprecated the unfortunate condition of the country, expressed his hopes that extreme measures would not be resorted to, avowed his love for the profession with which from early childhood he had been identified and in which so many of his family had distinguished connection. There were suavity in his manner and kindly sentiments in his remarks, but not that earnest, devoted patriotism which the times demanded, and which broke forth from others of his profession, in denunciation of treason and infidelity to the flag. Porter had presented himself but once to the Department, and that was to make some inquiries in relation to his orders to the Pacific, but there was no allusion to the impending difficulties nor any proffer of service if difficulties ensued. As with many others, some of whom abandoned the Government, while some remained and rendered valuable service, the Department was in doubt what course these two officers would pursue.

This was the state of the case when the instructions of the 1st of April were sent me. On learning from the President who were Mr. Seward’s associates, I was satisfied that Porter had through him proposed and urged the substitution of Barron for Stringham as the detailing and confidential officer of the Secretary of the Navy. I was unwilling to believe that my colleague Mr. Seward could connive at, or be party to, so improper and gross an affair as to interfere with the organization of my Department, and jeopardize its operations at such a juncture. What, then, were the contrivances which he was maturing with two young officers, one of the army and the other of the Navy, without consulting the Secretary of War or the Secretary of the Navy? What had he, the Secretary of State, to do with these officers in any respect? I could get no satisfactory explanation from the President of the origin of this strange interference, which mystified him, and which he censured and condemned more severely than myself. He assured me it would never occur again. Although very much disturbed by the disclosure, he was anxious to avoid difficulty, and, to shield Mr. Seward, took to himself the whole blame and repeatedly said that I must pay no more attention to the papers sent me than I thought advisable. He gave me, however, at that time no information of the scheme which Mr. Seward had promoted, farther than that it was a specialty, which Mr. Seward wished should be kept secret. I therefore pressed for no further disclosures.

The instructions in relation to Barron I treated as nullities. My first conclusions were that Mr. Seward had been made a victim to an intrigue, artfully contrived by those who favored and were promoting the Rebellion, and that the paper had been in some way surreptitiously introduced with others in the hurry and confusion of that busy day without his knowledge. That he would commit the discourtesy of imposing on me such instructions I was unwilling to believe, and that he should be instrumental in placing, or attempting to place, a person more than suspected, and who was occupying so equivocal a position as Barron, in so responsible a position in the Navy Department, and commit to him all the information of that branch of the Government, seemed to me impossible.

![]()

![]()