HEADQUARTERS, CHARLESTON, S.C.,

February 13, 1861.

Hon. HOWELL COBB,

President of the Provisional Congress:

SIR: I had the honor last night to acknowledge the receipt of your telegram, in which you informed me that the Provisional Congress had taken charge of the “questions and difficulties” now existing between the several States of the Confederacy and the Government of the United States.In the reply made to you by telegraph I stated that I would communicate with you by letter, and added to it the expression of the urgent conviction of the authorities of the State as to the period in which the reduction of Fort Sumter should be complete. And, in the first place, let me offer you my warm congratulations upon the success which has attended you in the organization of the Provisional Government. May it be equal to the emergency of every occasion which can arise, and be to each State in this new confederation the efficient guardian of those rights, which, ignored or usurped under the former confederation, has united these States in the bonds of a new political compact.

In taking charge of the “questions and difficulties” which relate to Fort Sumter, it will be necessary for the Congress to apprehend rightly their present position. The force of circumstances devolved upon this State an obligation to provide the measures necessary for its defense. It has been obliged to act under the guidance of its own counsels, but has never forgotten the interest of its sister States in every measure which it was about to provide for its own safety. And I beg to assure you that, in all which it may at any time do, a regard for the welfare and wishes of its sister States in the new confederation will exercise a marked influence upon the conduct of this State.

The “questions and difficulties” of Fort Sumter can scarcely be fully appreciated, unless by those who have been familiar with its progress from the commencement of its history to the present moment. If it shall appear otherwise, it has, nevertheless, been the constant, anxious desire of this State to obtain the possession of a fort which, held by the United States, affected its dignity and safety without a collision, which would involve the loss of life. To secure this end every form of negotiation which could be adopted, in consistency with the dignity of the State, or had the promise or seeming of success, has been honestly attempted. To all of these attempts there has been but one result: A refusal in all cases, positive and unqualified, varied only as to the reasons which were set forth for its justification? has followed each demand. And now the conviction is presented to the State, derived from the most calm and deliberate consideration of the whole matter, that in this persistent refusal of the President of the United States is involved a denial of the rightful independence of the State of South Carolina.

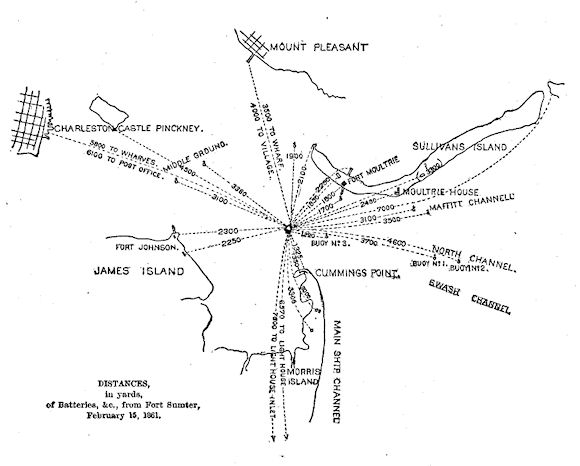

The questions and difficulties, therefore, of Fort Sumter, comprehend now, as you will perceive, considerations which are political as well as military; and it would scarcely be considered that an undue estimate was made of the former if they were said to be as important as the latter. The establishment of them, moreover, is of the utmost consequence to every State which has united with this State in the bonds of a new confederation. The State has held its right to the possession of Fort Sumter to be the direct and necessary consequence of its right, as a sovereign State, to have the control of a military post within its limits, which post, during the period of the political connection of the State with the other States, was held by the United States for the protection of South Carolina because South Carolina was a part of the United States, and being so, upon the United States was devolved the obligation to provide that defense for this State. With the termination of the political connection between South Carolina and the United States the obligation of the United States to defend that State ceased, unless that State itself was the property of the United States. If the State was an independent power the rightful control within its limits of a military post, which involved its dignity and affected its safety, was and is recognized by the plainest rules of public law. The denial, therefore, of the right of the State to have possession of the fort was, in fact, a denial of its independence. Nor has there been even a colorable pretext for a consistency of that possession by the United States with the independence of the State, since the President authorized the distinct avowal that it was held as a military post. The sole use of it as a military post is in the control (called by the President the protection) it gives to the United States of the harbor of Charleston. The assertion, then, as you will perceive, of the rightful independence of the State carries necessarily with it the right to reduce Fort Sumter into its own possession, which is held, as it is, by a hostile power, for an unfriendly purpose. It is a hostile power when it asserts a right to exercise a dominion over the State, which that State refuses to recognize as consistent with its own dignity and safety; and its purpose cannot be otherwise than unfriendly when it can only be to enable the United States to commit to its military subordinates a power to refuse “to permit any vessels to pass within range of the guns” which are within its walls. It has, therefore, been considered at once proper and necessary for this State to take possession of that fort as soon as the measures necessary for the accomplishment of that result can be completed, and it is now expected that within a short time all the arrangements will be perfected necessary for its certain and speedy reduction. With the completion of these preparations and the assurance they afford of success, it has ever been the purpose of the authorities of this State to take this fort into the possession of the State. The right to do so has been considered the right of the State, and the resources of the State have been considered equal to the exercise of that right.

Whatever may be the mode in which the Congress will take charge of these “questions and difficulties,” I trust that it is considered that in the solution of them you will regard the position which the State of South Carolina now occupies in relation to them. That position is marked by these propositions: That the right to have possession of the fort is a right incident to the independence (she) the State has asserted; that, to obtain possession of the fort, she has exhausted all modes which, consistently with her dignity, can be devised for a peaceful settlement; that the failure of such attempts has remitted her to the necessity of employing force to obtain that which should have been yielded from considerations of justice and right, and that as soon as her preparations are completed the reduction of that fort should be accomplished.

In the absence of any explanation or direction connected with the telegram received from you, I have assumed that the policy and measures which have been adopted by this State, and which are in prosecution, will be recognized as proper. In the consideration of the question of Fort Sumter, I have not been insensible of those matters which are in their nature consequential, and have, I trust, weighed, with all the care which befits the grave responsibilities of the case, the various circumstances which determine the time when this attack should be made. With the best lights which I could procure in guiding or assisting me, I am perfectly satisfied that the welfare of the new confederation and the necessities of the State require that Fort Sumter should be reduced before the close of the present administration at Washington. If an attack is delayed until after the inauguration of the incoming President of the United States, the troops now gathered in the capital may then be employed in attempting that which, previous to that time, they could not be spared to do. They dare not leave Washington now and do that which then will be a measure too inviting to be resisted.

Mr. Lincoln cannot do more for this State than Mr. Buchanan has done. Mr. Lincoln will not concede what Mr. Buchanan has refused. Mr. Buchanan has placed his refusal upon grounds which determine his reply to six States, as completely as to the same demand if made by a single State.

If peace can be secured, it will be by the prompt use of the occasion, when the forces of the United States are withheld from our harbor. If war can be averted, it will be by making the capture of Fort Sumter a fact accomplished during the continuance of the present administration, and leaving to the incoming administration the question of an open declaration of war. Such a declaration, separated, as it will be, from any present act of hostilities during Mr. Lincoln’s administration, may become to him a matter requiring consideration. That consideration will not be expected of him, if the attack on the fort is made during his administration, and becomes, therefore, as to him, an act of present hostility. Mr. Buchanan cannot resist, because he has not the power. Mr. Lincoln may not attack, because the cause of the quarrel will have been, or may be, considered by him as past.

Upon this line of policy I have acted, and upon the adherence to it may be found, I think, the most rational expectation of seeing that fort, which is even now a source of danger to the State, restored to the possession of the State without those consequences which I should most deeply deplore. Should such consequences, nevertheless, follow from an adherence to this policy, however much I would regret the occurrence, I should feel a perfect assurance that, in happening under such circumstances, they demonstrated conclusively that, under the evil passions which blind and mislead those who govern the United States, no human power could have averted the attempted overthrow of these States; and that, in the exhibition of an ability by the States of the new confederation to maintain their rights, there could be found satisfaction in the reflection that their sufferings at this time might purchase for them quiet and happiness in time to come.

I have the honor to be, with great respect, your obedient servant,

F. W. PICKENS,

Governor of South Carolina.

![]()