.

.

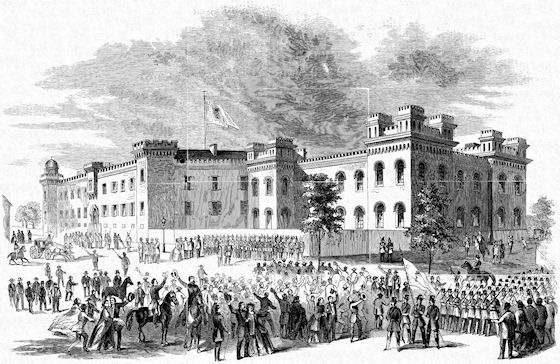

.FORT MOULTRIE, S. C., December 6, 1860.

(Received A. G. O., December 10.)

Col. S. COOPER,

Adjutant-General U. S. Army:

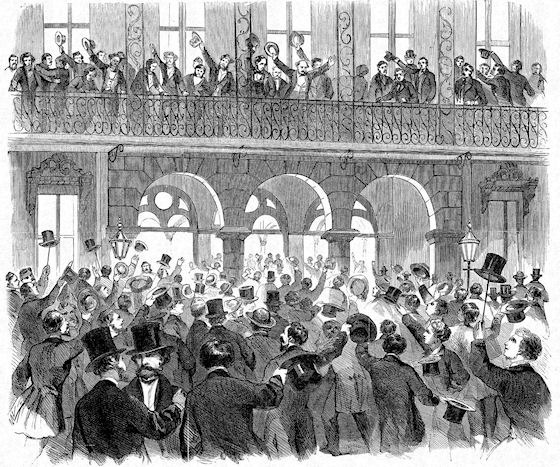

COLONEL: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt, on the 4th, of your communication of the 1st instant. In compliance therewith I went yesterday to the city of Charleston to confer with Colonel Huger, and I called with him upon the mayor of the city, and upon several other prominent citizens. All seemed determined, as far as their influence or power extends, to prevent an attack by a mob on our fort; but all are equally decided in the opinion that the forts must be theirs after secession. I shall nevertheless, knowing how excitable this community is, continue to keep on the qui vive, and, as far as in my power, steadily prepare my command to the uttermost to resist any attack that may be made. As the State will probably declare itself out of the Union in less than two weeks, it seems to me that it would be well to discontinue all engineering work on this fort except such as is necessary to increase its strength. I have not pretended to exercise any control over that department, and have found Captain Foster generally disposed to accede to the suggestions I have ventured to make; and the suggestions I now make are not made in any unkind spirit towards him, as he is compelled to carry out the instructions of his department, but such as I feel it my duty to make, as being held responsible for the defense of this work. One of the bastionettes is nearly completed, now awaiting the arrival of the pintle blocks, without which the embrasure cannot be made. The foundation has only been laid for the other. I certainly think that it is now too late to begin the construction of the second one, and that it would be better to substitute some other flanking arrangement, which can be finished in a few days.

Captain Foster is now sodding the exterior slope of the ditch, and putting muck on the glacis. It seems to me that that work had better be discontinued, and the planking, &c., removed, as it might be used by an investing or attacking force.

In other words, I would now apply our science to devising and placing in front of and on our walls every available means of embarrassing and preventing an enemy scaling our low walls. Anything that will obstruct his advance will be of great advantage to our weak garrison.

Our time is short enough for what we have to do. Should the ordnance stores I have called for or re-enforcements not arrive, in the event of our being attacked I fear that we shall not distinguish ourselves by holding out many days.

I have not yet commenced leveling off the sand hills which, within one hundred and sixty yards to the east, command this fort. Would my doing this be construed into initiating a collision? I would think you also to inform me under what circumstances I would be justified in setting fire to or destroying the houses which afford dangerous shelter to an enemy, and whether I would be justified in firing upon an armed body which may be seen approaching our works.

Captain Foster told me yesterday that he found that the men of his Fort Sumter force, who he thought were perfectly reliable, will not fight if an armed force approaches that work; and I fear that the same may be anticipated from the Castle Pinckney force.

I learn that in consequence of the decayed condition of the carriages at Fort Sumter, the guns have not been mounted there as I reported they were to have been. If that work is not to be garrisoned, the guns certainly ought not to be mounted, as they may be turned upon us.

The remark has, I hear, been repeatedly made in the city that if they need heavy guns, they call get them in forty-eight hours. This, I suppose, refers to their being able to bring them from Fort Pulaski, mouth of the Savannah River.

Colonel Huger designs, I think, leaving Charleston for Washington to-morrow night. He is more hopeful of a settlement of impending difficulties without bloodshed than I am. Hoping in God that he may be right in his opinion,

I am, colonel, respectfully, your obedient servant,

ROBERT ANDERSON,

Major, First Artillery, Commanding.