.

.FORT MOULTRIE, S.C., November 28, 1860.

Col. S. COOPER,

Adjutant-General U. S. A.:

“I am inclined to think that if I had been here before the commencement of expenditures on this work, and supposed that this garrison would not be increased, I should have advised its withdrawal, with the exception of a small guard, and its removal to Fort Sumter, which so perfectly commands the harbor and this fort.

COLONEL: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your communication of the 24th instant. I presume that my letter of the 23d has been received, and that the Department is now in possession of my views in reference to the measures I deem advisable and necessary for keeping this work and this harbor. Your letter confines my answer to what refers to the work under my charge. I cannot but remark that I think its security from attack would be more greatly increased by throwing garrisons into Castle Pinckney and Fort Sumter than by anything that can be done in strengthening the defenses of this work. There are several intelligent and efficient men in this community, who, by intimate intercourse with our Army officers, have become perfectly well acquainted with this fort, its weak points, and the best means of attack. There appears to be a romantic desire urging the South Carolinians to have possession of this work, which was so nobly defended by their ancestors in 1776; and the State, if she determines to act on the aggressive, will exert herself to take this work. The accompanying report exhibits the present state of my command. I think I can rely upon their doing their duty, but you will see how sadly deficient we are in numbers, whether to repel a coup de main or to maintain a siege. We finished mounting our guns this morning, and I shall soon commence drilling and exercising my men in firing with muskets and cannon. I find that in consequence of sickness, &c., very little military duty has been attended to here for a long time; we shall try, and I hope to succeed in regaining the lost ground. This work, when Captain Foster finishes the ditch, counterscarp, and bastionettes on which he is now at work, and executes the addition of a half battery at the northwest angle of the fort, which I have urged him to commence immediately, will be in good condition. I would have preferred having a ditch (wet), but the captain informs me that he could not make it, in consequence of the quicksand. I will send a requisition in a few days (I am very constantly occupied now) for certain ordnance stores. Among them I shall embrace a couple of Coehorns, say four mountain howitzers and twenty of the heaviest revolvers, with a supply of ammunition. I believe that we have no muskets for firing several charges. I would have been pleased to get four of them for the half bastion, but if there are none I will replace them by something else. I would like to get these articles as soon as possible, as I wish to practice our men with the different arms I may have to use. God forbid, though, that I should do so. Colonel Huger has just left me; he came down stating that there was the greatest excitement in the city on account of a rumor that the Adger was bringing out four companies. Some of the gentlemen were in favor of taking steamers and going out to intercept the Adger. He has just returned. I told him that I had no intelligence of anything of the kind.

In reply to the suggestion of the honorable Secretary about the expediency of employing reliable persons not connected with the military service, for purposes of fatigue and police, I must say that I doubt whether such could be obtained here. They would certainly be of great assistance to us. The excitement here is too great. Captain Foster informs me that an adjutant of a South Carolina regiment applied to him for his rolls, stating that he wished to enroll the men for military duty. The captain told him that they had no right to do it, as the men were in the pay of the United States Government. I presume that every able-bodied man in this part Of the State, not in the service of the General Government, is now being or has been enrolled.

I will thank the Government to give me special instructions in reference to a question which may arise in these cases:

What shall I do if the State authorities demand from Captain Foster men who they may aver have been enrolled into the State service? Captain Foster will probably send such cases to me; what shall I do with them?

I hope that my command will very soon be strengthened, so far at the least as filling up these companies to the legal standard. This would enable me, at all events, to have our proper garrison military duties properly attended to.

I am inclined to think that if I had been here before the commencement of expenditures on this work, and supposed that this garrison would not be increased, I should have advised its withdrawal, with the exception of a small guard, and its removal to Fort Sumter, which so perfectly commands the harbor and this fort.

I am, colonel, respectfully, your obedient servant,

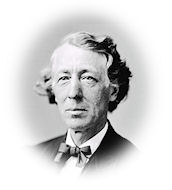

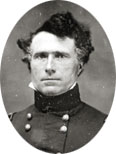

ROBERT ANDERSON,

Major, First Regiment Artillery, Commanding.