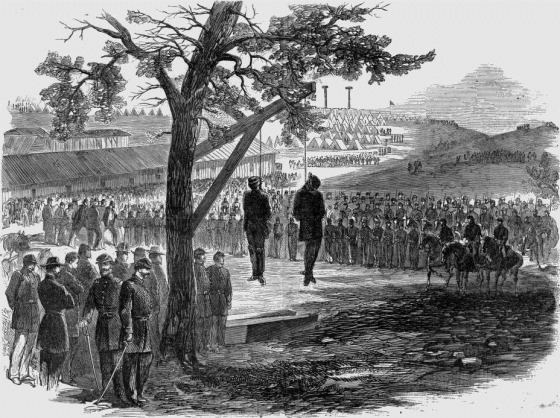

Execution, By Hanging, Of Two Rebel Spies, Williams and Peters, In the Army of the Cumberland, June 9, 1863.

__________

Note: The following article provides a perspective from the day of the execution. An article, “Williams, C.S.A.”, published in Harper’s Monthly Magazine nearly 50 years later, fleshes out the story more fully, with dispatches, telegrams, and other material related to the incident. – MpG 6/2/2013

__________

Harper’s Weekly, July 4, 1863.

We are indebted to Mr. James K. Magie, of the 78th Illinois Regiment, for the sketch of the execution of the two rebel spies, Williams and Peters, who were hanged by General Rosecrans on 9th inst. The following account of the affair is from a letter written by the surgeon of the 85th Indiana:

Headquarters Post,

Franklin, Tennessee.

June 9, 1863.

Last evening about sundown two strangers rode into camp and called at Colonel Baird’s head-quarters, who presented unusual appearances. They had on citizens’ overcoats, Federal regulation pants and caps. The caps were covered with white flannel havelocks. They wore sidearms, and showed high intelligence. One claimed to be a colonel in the United States Army, and called himself Colonel Austin; the other called himself Major Dunlap, and both representing themselves as Inspector-Generals of the United States Army. They represented that they were now out on an expedition in this department, inspecting the outposts and defenses, and that day before yesterday they had been overhauled by the enemy and lost their coats and purses. They exhibited official papers from General Rosecrans, and also from the War Department at Washington, confirming their rank and business. These were all right to Colonel Bayard, and at first satisfied him of their honesty. They asked the Colonel to loan them $50, as they had no coats and no money to buy them. Colonel Baird loaned them the money, and took Colonel Austin’s note for it. Just at dark they started, saying they were going to Nashville, and took that way. Just so soon as their horses’ heads were turned the thought of their being spies struck Colonel Baird, he says, like a thunder-bolt, and he ordered Colonel Watkins, of the 6th Kentucky cavalry, who was standing by, to arrest them immediately. But they were going at lightning speed. Colonel Watkins had no time to call a guard, and only with his orderly he set out on the chase. He ordered the orderly to unsling his carbine, and if, when he (the Colonel) halted them they showed any suspicious motions, to fire on them without waiting for an order. They were overtaken about one-third of a mile from here. Colonel Watkins told them that Colonel Baird wanted to make some further inquiries of them, and asked them to return. This they politely consented to do, after some remonstrance on account of the lateness of the hour and the distance they had to travel, and Colonel Watkins led them to his tent, where he placed a strong guard over them. It was not until one of them attempted to pass the guard at the door that they even suspected they were prisoners. Colonel Watkins immediately brought them to Colonel Baird under strong guard. They at once manifested great uneasiness, and pretended great indignation at being thus treated. Colonel Baird frankly told them that he had his suspicions of their true character, and that they should, if loyal, object to no necessary caution. They were very hard to satisfy, and were in a great hurry to get off. Colonel Baird told them that they were under arrest, and he should hold them prisoners until he was fully satisfied that they were what they purported to be. He immediately telegraphed to General Rosecrans, and received the answer that he knew nothing of any such men, that there were no such men in his employ, or had his pass.

Long before this dispatch was received, however, every one who had an opportunity of hearing their conversation was well satisfied that they were spies. Smart as they were, they gave frequent and distinct evidence of duplicity. After this dispatch came to hand, which it did about 12 o’clock (midnight), a search of their persons was ordered. To this the Major consented without opposition, but the Colonel protested against it, and even put his hand to his arms. But resistance was useless, and both submitted. When the Major’s sword was drawn from the scabbard there were found etched upon it these words, “Lt. W. G. Peter, C.S.A.” At this discovery Colonel Baird remarked, “Gentlemen, you have played this d—d well.” “Yes,” said Lieutenant Peter, “and it came near being a perfect success.” They then confessed the whole matter, and upon further search various papers showing their guilt were discovered upon their persons. Lieutenant Peter was found to have on a rebel cap, secreted by the white flannel havelock.

Colonel Baird immediately telegraphed the facts to General Rosecrans and asked what he should do, and in a short time received an order “to try them by a drum-head court-martial, and if found guilty hang them immediately.” The court was convened, and before daylight the case was decided, and the prisoners informed that they must prepare for immediate death by hanging.

At daylight men were detailed to make a scaffold. The prisoners were visited by the Chaplain of the 78th Illinois, who, upon their request, administered the sacrament to them. They also wrote some letters to their friends, and deposited their jewelry, silver cups, and other valuables for transmission to their friends.

The gallows was constructed by a wild cherry-tree not far from the depot, and in a very public place. Two ropes hung dangling from the beam, reaching within eight feet of the ground. A little after nine o’clock A.M. the whole garrison was marshaled around the place of execution in solemn sadness. Two poplar coffins were lying a few feet away. Twenty minutes past nine the guards conducted the prisoners to the scaffold—they walked firm and steady, as if unmindful of the fearful precipice which they were approaching. The guards did them the honor to march with arms reversed.

Arrived at the place of execution they stepped upon the platform of the cart and took their respective places. The Provost Marshal, Captain Alexander, then tied a linen handkerchief over the face of each and adjusted the ropes. They then asked the privilege of bidding last farewell, which being granted, they tenderly embraced each other. This over, the cart moved from under them, and they hung in the air. What a fearful penalty! They swung off at 9:30—in two minutes the Lieutenant ceased to struggle. The Colonel caught hold of the rope with both hands and raised himself up at 3 minutes, and ceased to struggle at 5 minutes. At 6 minutes Dr. Forester, Surgeon 6th Kentucky Cavalry, and Dr. Moss, 78th Illinois Infantry, and myself, who had been detailed to examine the bodies, approached them, and found the pulse of both full and strong. At 7 minutes the Colonel shrugged his shoulders. The pulse of each continued to beat 17 minutes, and at 20 minutes all signs of life had ceased. The bodies were cut down at 30 minutes and encoffined in full dress. The Colonel was buried with a gold locket and chain on his neck. The locket contained the portrait and a braid of hair of his intended wife—her portrait was also in his vest pocket—these were buried with him. Both men were buried in the same grave—companions in life, misfortune, and crime, companions in infamy, and now companions in the grave.

I should have stated in another place that the prisoners did not want their punishment delayed; but, well knowing the consequences of their acts, even before their trial, asked to have the sentence, be it by hanging or shooting, quickly decided and executed. But they deprecated the idea of death by hanging, and asked for a communication of the sentence to shooting.

The elder and leader of these unfortunate men was Lawrence Williams, of Georgetown, D. C. He was as fine-looking a man as I have ever seen, about six feet high, and perhaps 30 years old. He was a son of Captain Williams, who was killed at the battle of Monterey. He was one of the most intellectual and accomplished men I have ever known. I have never known any one who excelled him as a talker. He was a member of the regular army, with the rank of captain of cavalry, when the rebellion broke out, and at that time was aid-de-camp and private secretary to General Winfield Scott. From this confidence and respect shown him by so distinguished a man may be judged his education and accomplishments. He was a first cousin of General Lee, commanding the Confederate army on the Rappahannock. Soon after the war began he was frank enough to inform General Scott that all his sympathies were with the South, as his friends and interests were there, and that he could not fight against them. As he was privy to all of General Scott’s plans for the campaign, it was not thought proper to turn him loose, hence he was sent to Governor’s Island, where he remained three months. After the first Bull Run battle he was allowed to go South, where he joined the Confederate army, and his subsequent history I have not been able to learn much about. He was a while on General Bragg’s staff as Chief of Artillery, but at the time of his death was his Inspector-General. When he joined the Confederate army he altered his name, and now signs it thus: “Lawrance W. Orton, Col. City. P. A. C. S. A.”—(Provisional Army Confederate States of America). Sometimes he writes his name “Orton,” and sometimes “Anton,” according to the object which he had in view. This we learn from the papers found on him. These facts in relation to the personal history of Colonel Orton I have gathered from the Colonel himself and from Colonel Watkins, who knows him well, they having belonged to the same regiment of the regular army—2d U. S. Cavalry. Colonel Watkins, however, did not recognize Colonel Orton until after he had made himself known, and now mourns his apostasy and tragic fate.

The other victim of this delusive and reckless daring was Walter G. Peter, a lieutenant in the rebel army, and Colonel Orton’s adjutant. He was a tall, handsome young man, of about twenty-five years, that gave many signs of education and refinement.

Of his history I have been able to gather nothing. He played but a second part. Colonel Orton was the leader, and did all the talking and managing. Such is a succinct account of one of the most daring enterprises that men ever engaged in. Such were the characters and the men who played the awful tragedy.

History will hardly furnish its parallel in the character and standing of the parties, the boldness and daring of the enterprise, and the swiftness with which discovery and punishment were visited upon them. They came into our camp and went all through it, minutely inspecting our position, works, and forces, with a portion of their traitorous insignia upon them; and the boldness of their conduct made their flimsy subterfuges almost successful.