Near Fredericksburg,

Nov. 19th, 1862.

My dear Mother:

Here we are at last on familiar ground, lying in camp at Falmouth, opposite to Fredericksburg. I have been unable while on the march for the few days past, to write you, but am doing my best with a pencil to-night, as one of our Captains returns home to-morrow, and will take such letters as may be given him. It was my turn to go home this time, but my claim was disregarded. You know Lt.-Col. Morrison has command of the Regiment in Col. Farnsworth’s absence, and Morrison never omits any opportunity to subject me to petty annoyances. I am an American in a Scotch Regiment, and in truth not wanted. Yet I cannot resign. The law does not allow that, so I have to bear a great deal of meanness. Stevens in his lifetime, knowing how things stood, kept in check the Scotch feeling against interlopers like Elliott and myself. … I do not exaggerate these things. I used to feel the same way in old times, but had been so long separated from the regiment as almost to forget them. I have borne them of late without complaint, hoping the efforts of my friends might work my release. In the Regiments of the old Division I think no officer had so many strong friends as I. In my own Regiment I may say that I am friendless. (I except McDonald). In the Division I had a reputation. In my Regiment I have none. After eighteen months of service I am forced to bear the insults of a man who is continually telling of the sacrifices he has made for his country because he abandoned, on leaving for the war, a small shop where he made a living by polishing brasses for andirons.

Forgive me, my dear mother, for complaining. It does me good sometimes, for then, after speaking freely, I always determine afresh that if these things must be, I will nevertheless do my duty, and in so doing maintain my self-respect. Love to all, dear mother. Good-bye.

Very afFec’y.,

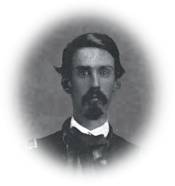

William T. Lusk.