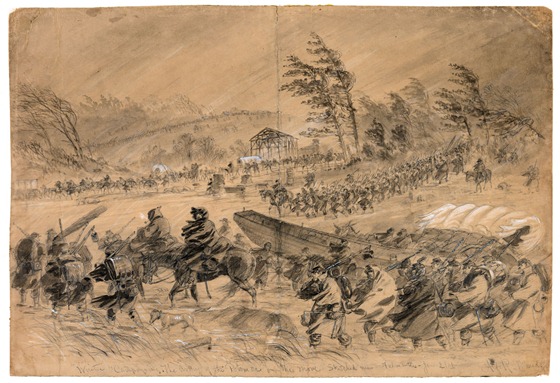

Summary: Exhibit caption: Alfred R. Waud depicts Union forces coping with the challenge of winter weather in 1863 as they advanced toward the Rappahannock River. He skillfully delineates formations of soldiers, wagons, and animals traversing the foreground, middle ground, and background of the scene and vividly captures the impact of blustery winter wind and snow in their bent and bowed forms. The British-born Waud won wide acclaim for his visual reportage of Civil War battles and soldiers’ living conditions because he incorporated impressive amounts of accurately observed details into compositions that convey strong expressive effects. More than 1,200 sketches he created for Harper’s Weekly are preserved in the Prints & Photographs Division. (January 21, 1863. Library of Congress image.)

The New York Times correspondent wrote of the night depicted in the image:

It was a wild Walpurgus night, such as Goethe paints in the “Faust” while the demons held revel in the forest of the Brocken. All hopes that it would be a “mere shower” were presently blasted. It was evident we were in for a regular northeaster, and among the roughest of that rough type. Yet was there hard work done that fearful night. One hundred and fifty pieces of artillery were to be planted in the position selected for them by General Hunt, Chief of Artillery—a man of rare energy and of a high order of professional skill. The pontoons, also, were drawn down nearer toward the river, but it was dreadful work; the roads under the influence of the rain were becoming shocking; and by daylight, when the boats should all have been on the banks, ready to slide down into the water, but fifteen had been gotten up—not enough for one bridge, and five were wanted!

The night operations had not escaped the attention of the wary rebels. Early in the morning a signal-gun was fired opposite the ford, reminding one of that other signal-gun fired by them on the morning of Thursday the 11th December, when we began laying the pontoon opposite Fredericksburg, and which was the token for the concentration of the whole force at that point. It was indispensable that we should secure all the advantages of a surprise; and though our intention was thus blown to their ears early on Wednesday morning, we were, nevertheless, forty-eight hours ahead of them, and with favorable conditions should have been able to carry our position before they could possibly concentrate.

Accordingly a desperate effort was made by the Commanding General to get ready the bridges. It was obvious, however, that, even if completed, it would be impossible for us, in the then condition of the ground, to get a single piece of artillery up the opposite declivity. It would be necessary to rely wholly upon the infantry—indeed, wholly on the bayonet. Happily, if the rebels should prove to be in strong force, the country is too thickly wooded to admit of much generalship, and it was hoped that our superior weight of metal would carry the day.

Early in the forenoon I rode up to the head-quarters of Generals Hooker and Franklin, about two miles from Banks’s Ford. The night’s rain had made deplorable havoc with the roads. The nature of the upper geologic deposits of this region affords unequaled elements for bad roads. The sand makes the soil pliable, the clay makes it sticky, and the two together form a road out of which, when it rains, the bottom drops, but which is at the same time so tenacious that extrication from its clutch is all but impossible.

The utmost effort was put forth to get pontoons enough into position to construct a bridge or two. Double and triple teams of horses and mules were harnessed to each pontoon-boat. It was in vain. Long, powerful ropes were then attached to the teams, and a hundred and fifty men were put to the task on each boat. The effort was but little more successful. They would flounder through the mire for a few feet—the gang of Liliputians with their huge-ribbed Gulliver—and then give up breathless. Night arrived, but the pontoons could not be got up. The rebels had discovered what was up, and the pickets on the opposite bank called over to ours that they “would come over to-morrow and help us build the bridge.”

That night the troops again bivouacked in the same position in the woods they had held the night before. You can imagine it must have been a desperate experience—and yet not by any means as bad as might be supposed. The men were in the woods, which afforded them some shelter from the wind and rain, and gave them a comparatively dry bottom to sleep on. Many had brought their shelter-tents; and making a flooring of spruce, hemlock, or cedar boughs, and lighting huge camp fires, they enjoyed themselves as well as the circumstances would permit. On the following morning a whisky ration, provided by the judicious forethought of General Burnside, was on hand for them.

Thursday morning saw the light struggling through an opaque envelop of mist, and dawned upon another day of storm and rain. It was a curious sight presented by the army as we rode over the ground; miles in extent, occupied by it. One might fancy some new geologic cataclysm had o’ertaken the world; and that he saw around him the elemental wrecks left by another Deluge. An indescribable chaos of pontoons, wagons, and artillery encumbered the road down to the river—supply-wagons upset by the road-side—artillery “stalled” in the mud—ammunition. trains mired by the way. Horses and mules dropped down dead, exhausted with the effort to move their loads through the hideous medium. A hundred and fifty dead animals, many of them buried in the liquid muck, were counted in the course of a morning’s ride. And the muddle was still further increased by the bad arrangements—or rather the failure to execute the arrangements that had been made. It was designed that Franklin’s column should advance by one road and hooker’s by another. But, by mistake, a portion of the troops of the Left, Grand Division debouched into the road assigned to the centre, and cutting in between two divisions of one of Hooker’s corps, threw every thing into confusion. In consequence, the woods and roads have for the past two days been filled with stragglers, though very many of them were involuntary stragglers, and were evidently honestly seeking to rejoin their regiments. It was now no longer a question of how to go on; it was a question of how to get back.