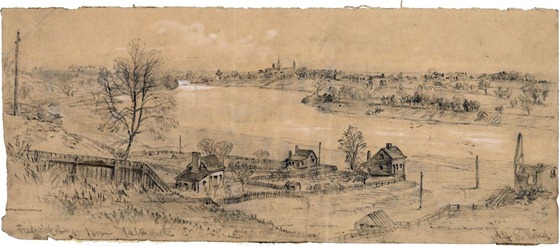

Camp three miles north of Fredericksburg,

Saturday, Dec. 6, 1862.

Dear Sister L.:—

We have been here a couple of weeks now, and things begin to look some like winter quarters. The papers still keep up the hue and cry of “on to Richmond,” but we don’t go on to Richmond, and my “opg.” is we won’t this winter. The fact is, winter is upon us, and winter in Virginia, though very different from northern winters, is just as fatal to a campaign as frost is to cucumbers, or arsenic to rats. The moving of an army implies more than the marching of the men that compose it. Long trains of wagons, heavier wagons, too, than you ever saw, must accompany each division. Batteries of artillery, too, and when a few of these have passed along a road after one or two days’ rain or snow, the following teams are floundering belly deep in mud, and everything must stop. Now, notwithstanding what the papers say, I believe they know it is not the intention to advance on Richmond this winter. My own opinion is (you may have it for its worth) that we will stay here a month or so till the mud will prevent the rebs from moving north, and then if Congress has not done anything in the way of settling the matter, we will be sent south where winter will not hinder our fighting.

I have been much interested in the President’s message. I presume you have read it, at least that part relating to emancipation. It meets my views exactly. It is broad and deep, but yet so simple a child can understand it. Nothing he has ever said or done pleased me so much as his reasons for his policy, and his earnest appeal to Congress and the people to support it. “We say we are for the Union,” he says, “but while we say so the world does not forget we do know how to save the Union. . . . We shall nobly save or meanly lose the last best hope of earth.”

I do hope that Congress will heartily support his plan, and remembering that “the dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present” will “rise to the occasion.”

I think I wrote to you at Warrenton what I thought of McClellan’s removal, but if you did not receive my letter I will tell you in a few words. I think the whole army thinks as much of McClellan to-day as they ever did. We ask no better leader. I believe, too, that the President had as much confidence in his loyalty and ability the day he removed him as he ever had. “Why did he remove him then?” you will ask. On account of pressure of public opinion. There was a strong feeling among the people that he was not the right man, and they had lost confidence in him. They could not understand the difficulties of his position, and chafed at his delays. Time will show if they were right. The President saw that the people did not like him, would not enlist, would not come forward with their money, and thought best, though against his better judgment, to yield. Now, that is my opinion. It is not what the public press says, but merely what I think, and as I said before, you may have it for what it is worth. Burnside was a good man in his place, but not equal to “Little Mac.” His race is almost run.

I sympathize with you in your sorrow at the loss of one of your household band. Though I never knew her. I can almost read your hearts, as I fancy you gathering round the fireside or the table and missing her from the circle. The blow will be sudden and severe on Albert. I have often thought how I should feel if news should reach me of the death or dangerous illness of any of my dear friends while I was kept away from them. So far I have been spared the trial.

I am still established at brigade headquarters and very comfortably fixed, too. I am in a tent with two orderlies. We have built a log house just about seven by nine, five logs high, and covered it with ponchos. We have our bed in one end and a fireplace in the other, so we are quite comfortable. We need it, too, for yesterday it snowed and was bitter cold, and to-day it just thawed enough to be sloppy and nasty.

We have not been paid since we left the Peninsula, and money is scarce, I tell you. I don’t know but I shall have to stop writing for want of stamps. I must close this letter any way, for it is getting so dark I can’t see to write.