Sunday, 7th.—John and Alexander Smith came to-day and brought letter and some” comforts from home; sent letter and $50.00 home by Mr. Smith. From this until the 19th, we were doing nothing special except marching and camping around Bradyville and Readyville.

Friday, December 7, 2012

Sunday, 7th, December.

I have had a shock! While writing alone here (almost all have gone to church), I heard a step ascending the stair. What, I asked, if it should be Will? Then I blamed myself for supposing such a thing possible. Slowly it came nearer and nearer, I raised my head, and was greeted with a ghastly smile. I held out my hand. “Will!” “Sarah!” (Misery discards ceremony.) He stood before me the most woebegone, heartbroken man I ever saw.

With a forced laugh he said, “Where is my bride? Pshaw! I know she has gone to Clinton! I have come to talk to you. Was n’t it a merry wedding?” The hollow laugh rang again. I tried to jest, but failed. “Sit down and let me talk to you,” I said. He was in a wayward humor; cut to the heart, ready to submit to a touch of silk, or to resist a grasp of iron. This was the man I had to deal with, and get from him something he clung to as to — not his life, but — Miriam. And I know so little how to act in such a case, know so little about dealing gently with wild natures!

He alarmed me at first. His forced laugh ceased; he said that he meant to keep that license always. It was a joke on him yesterday, but with that in his possession, the tables would be turned on her. He would show it to her occasionally. It should keep her from marrying any one else. I said that it would be demanded, though; he must deliver it. The very devil shot in his eye as he exclaimed fiercely, “If any one dares demand it, I’ll die before giving it up! If God Almighty came, I’d say no! I’ll die with it first!” O merciful Father, I thought; what misery is to come of this jest. He must relinquish it. Gibbes will force him into it, or die in the attempt; George would come from Virginia. . . . Jimmy would cross the seas. . . . And I was alone in here to deal with such a spirit!

I commenced gently. Would he do Miriam such a wrong? It was no wrong, he said; let him follow his own will. “You profess to love her?” I asked. “Profess? Great God! how can you? I adore her! I tell you that, in spite of all this, I love her not more —that is impossible, — but as much as ever! Look at my face and ask that!” burst from him with the wildest impulse. “Very well. This girl you love, then, you mean to make miserable. You stand forever between her and her happiness, because you love her! Is this love?” He was sullenly silent. I went on: “Not only her happiness, but her honor is concerned. You who love her so, do her this foul injury.” “Would it affect her reputation?” he asked. “Ask yourself! Is it quite right that you should hold in your hands the evidence that she is Mrs. Carter, when you know she is not, and never will be? Is it quite honorable?” “In God’s name, would it injure Miriam? I’d rather die than grieve her.”

My iron was melted, but too hot to handle; I put it on one side, satisfied that I and I only had saved Miriam from injury and three brothers from bloodshed, by using his insane love as a lever. It does not look as hard here as it was in reality; but it was of the hardest struggles I ever had — indeed, it was desperate. I had touched the right key, and satisfied of success, turned the subject to let him believe he was following his own suggestions. When I told him he must free Miriam from all blame, that I had encouraged the jest against her repeated remonstrances, and was alone to blame, he generously took it on himself. “I was so crazy about her,” he said, “that I would have done it anyhow. I would have run any risk for the faintest chance of obtaining her”; and much more to the same purpose that, though very generous in him, did not satisfy my conscience. But he surprised me by saying that he was satisfied that if I had been in my room, and he had walked into the parlor with the license, she would have married him. What infatuation! He says, though, that I only prevented it; that my influence, by my mere presence, is stronger than his words. I don’t say that is so; but if I helped save her, thank Heaven!

It is impossible to say one half that passed, but he showed me his determination to act just as he has heretofore, and take it all as a joke, that no blame might be attached to her. “Besides, I’d rather die than not see her; I laugh, but you don’t know what I suffer!” Poor fellow! I saw it in his swimming eyes.

At last he got up to go before they returned from church. “Beg her to meet me as she always has. I told Mrs. Worley that she must treat her just the same, because I love her so. And — say I go to Clinton to-morrow to have that record effaced, and deliver up the license. I would not grieve her; indeed, I love her too well.” His voice trembled as well as his lips. He took my hand, saying, “You are hard on me. I could make her happy, I know, because I worship her so. I have been crazy about her for three years; you can’t call it a mere fancy. Why are you against me? But God bless you! Good-bye!” And he was gone.

Why? O Will, because I love my sister too much to see her miserable merely to make you happy!

Sunday, 7th—No news of importance. The weather is getting quite cool. The chaplain of our regiment is not with us at present and we have no preaching on Sundays, though we have prayer meeting in the evening. We had regular company inspection this evening. Our guard and picket duties are light at this place.

Sunday, 7. — Very cold, but pleasant winter weather. There is talk of the Kanawha freezing over. The river is low and a severe “spell” will do it. Cotton Mountain so slippery as to be dangerous to cross with teams or on horseback. Dr. Joe went over today to the Eighty-ninth to see Captain Brown of Chillicothe, whose mother is there. She was charged thirty dollars by a liveryman to bring her from Charleston, a distance of forty-six miles. Dr. Parker, of Berea, Cuyahoga County, agent of Sanitary Commission, visits us. We are in no condition for inspection, but he is a sensible man and will make proper allowances. Our sick in hospital is two, and excused from duty by surgeon eight. — Snow lying all around.

Camp Near Falmouth, Va.

December 7th, 1862.

My dear Mother:

We are still lying quietly in camp — no signs of a move yet, but general suffering for want of clothes, shoes in especial. The miserable article furnished by the Government to protect the feet of our soldiers seldom lasts more than three or four weeks, so it is easy to understand the constant cry of “no shoes” which is so often pleaded for the dilatoriness of the Army. I am, happily, well provided now, and can assure those of my friends that contributed to the box Capt. _____ brought me, that the box contained a world of comfort for which I heartily thank them. I think I have acknowledged the safe receipt of the box and its contents already, but a letter from Lilly says not. I will write Uncle Phelps that it came all right. I have had a rare treat to-day. Indeed I feel as though I had devoured a Thanksgiving Turkey. At least I have the satisfied feeling of one that has dined well. I did not dine on Peacock’s brains either, but — I write it gratefully — I dined on a dish of potatoes. They were cut thin, fried crisp, and tasted royally. You will understand my innocent enthusiasm, when I say that for nearly six weeks previous, I had not tasted a vegetable of any kind. There was nothing but fresh beef and hard crackers to be had all that time, varied sometimes by beef without any crackers, and then again by crackers without any beef. And here were fried potatoes! No stingy heap, but a splendid pile! There was more than a “right smart” of potatoes as the people would say about here. Excuse me, if warming with my theme I grow diffuse. The Chaplain and I mess together. The Chaplain said grace, and then we both commenced the attack. There were no words spoken. We both silently applied ourselves to the pleasant task of destruction. By-and-by there was only one piece left. We divided it. Then sighing, we turned to the fire, and lighted our pipes, smoking thoughtfully. At length I broke the silence. “Chaplain,” said I. “What?” says Chaplain. “Chaplain, they needed SALT!” I said energetically. Chap puffed out a stream of smoke approvingly, and then we both relapsed again into silence. I see a good deal of Capt. Stevens now, who says were his father only living I would have little difficulty in getting pushed ahead. He, poor fellow, feels himself very much neglected after the very splendid service he has rendered. It is exceedingly consoling, in reading the late lists of promotions made by the War Department, to see how very large a proportion has fallen to the share of young officers whose time has been spent at Fortress Monroe, Baltimore, or anywhere where there has been no fighting done. Perhaps our time may come one of these days, but I trust I may have better luck in the medical profession than at soldiering. However, I suppose when I get old, it will be a proud memory to have fought honorably at Antietam and South Mountain, in any capacity. I feel the matter more now, for I have been in the service so long, and so long in the same place, that I am fairly ashamed to visit old friends, all of whom hold comparatively high rank. I do not see why before the first of January, though, I should not be the Lt.-Col. of the 79th Regiment. In trying to be Major, I attempted to be frank and honorable, and lost. Now I shall try to act honorably, but mean to try and win.

I feel sad enough about Hannah. You know what inseparable playmates we were when children. God help her safely, whatsoever his will may be.

Love and kisses for all but gentlemen friends.

Affec’y.,

William.

Sunday, 7th. Up and off as early as usual. I carried a carbine and rode as usual in the ranks. Saw a large flock of wild turkeys. Advance ran after three “butternuts.” Took two horses. Saw any number of rebels around Diamond Grove. Encamped four miles west of Sherwood.

Oxford, Sunday, Dec. 7. Nothing new. Laid in camp. Many rumors afloat of Richmond taken, Bragg defeated, etc. Health improving.

“I begin to feel that my highest ambition is to make my brigade the best in the army, to merit and enjoy the affection of my men.”–Letters from Elisha Franklin Paxton.

Camp near Guiney’s Depot, December 7, 1862.

We have a quiet Sunday to-day. Everything in camp stopped except the axes, which run all night and all day, Sunday included. With the soldiers it is, “Keep the axes going or freeze.” They are the substitutes for tents, blankets, shoes, and everything once regarded as necessary for comfort. The misfortune is that even axes are scarce; the army is short of everything, and I fear soon to be destitute of everything. Yet the men are cheerful and seem to be contented. It seems strange, but, thanks to God for changing their natures, they bear in patience now what they once would have regarded as beyond human endurance. Whilst I write, I expect you are sitting in our pew at church, my place by your side filled by little Matthew,—bless the dear boy!—listening to a sermon from Parson White on covetousness, avarice and such kindred inventions of Satan. I wish him success, but I fear he will hardly be able to convince that leather can be too high, or that it is not the will of God for poor soldiers to go barefooted. God seems to have consigned one-half of our people to death at the hands of the enemy, and the other half to affluence and wealth realized by preying upon the necessities of those who are thus sacrificed. The extortioners at home are our worst enemies. If our soldiers had their sympathies, their assistance in providing the necessary means of sustaining the army, they might bear the hardships and do the work before them, feeling that it was a common undertaking for the benefit of us all and sustained by us all. But it seems like a revolution to make those rich who stay at home, and those poor who do their duty in the army.

I begin to like my new position. It occupies my whole mind and time. I begin to feel that my highest ambition is to make my brigade the best in the army, to merit and enjoy the affection of my men. I trust that both may be realized. When I came to it I knew that my appointment was unwelcome to some of the officers, but I have received nothing but kindness and respect from all. They all knew me, and knew that what I said would have to be done. I have had much better success thus far than I anticipated. We made a long march from Winchester— the longest the brigade has ever made without stopping. Usually on such marches the men fall behind, leave the road to get provisions at the farm-houses, etc. But on this march I came very near stopping such practices. Out of the five last days of the march, on three of them every man was present when we reached the camp in the evening; on the other two days but one was missing each day. I am sure that no other brigade in the army can show any such record. During this winter I shall spend my time in trying to make them comfortable and happy, in teaching them all the duties of soldiers, and in instilling into them the habit of obeying orders. I hope to gather in all absentees, and when the winter is over to turn out at least 2500 men for duty. So, you see, Love, I have laid out my work for the winter; and you, so far, as I have said, are to take no part of my care. I think I shall be able to devote a week to you at home. I wish that week were here now, but I can’t ask for it now. I must wait till the snow is deeper, the air colder. Then, I think, I will be allowed a short absence.

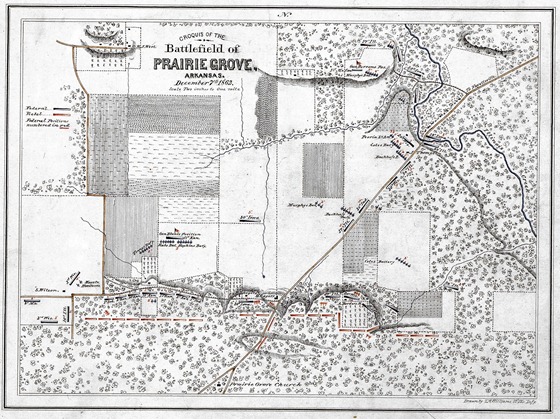

(click here or on image for larger version)

Croquis of the Battlefield of Prairie Grove, Arkansas. December 7th, 1862. Drawn by T. W. Williams, 15 Ills. Infy.

War Department. Office of the Chief of Engineers.

National Archives and Records Administration.

DECEMBER 7TH.—Last night was bitter cold, and this morning there was ice on my wash-stand, within five feet of the fire. Is this the “sunny South” the North is fighting to possess? How much suffering must be in the armies now encamped in Virginia! I sup-pose there are not less than 250,000 men in arms on the plains of Virginia, and many of them who survive the war will have cause to remember last night. Some must have perished, and thousands, no doubt, had frozen limbs. It is terrible, and few are aware that the greatest destruction of life, in such a war as this, is not produced by wounds received in battle, but by disease, contracted from exposure, etc., in inclement seasons. But the deadly bullet claims its victims. A friend just returned from the battle-field of June, near the city, whither he repaired to recover the remains of a relative, says the scene is still one of horror. So great was the slaughter (27th June) that we were unable to bury our own dead for several days, for the battle raged a whole week, and when the work was completed, the weather having been extremely hot, it was too late to inter the enemy effectually, so the earth was merely thrown over them, forming mounds, which the rains and the wind have since leveled. And now the ground is thickly strewn with the bleaching bones of the invaders. The flesh is gone, but their garments remain. He says he passed through a wood, not a tree of which escaped the missiles of the contending hosts. Most of the trees left standing are dead, being often perforated by scores of Minié-balls, but thousands were prostrated by cannon-balls and shells. It will long remain a scene of desolation, a monument of the folly and wickedness of man.

And what are we fighting for? What does the Northern Government propose to accomplish by the invasion? Is it supposed that six or eight million of free people can be exterminated? How many butchers would be required to accomplish the beneficent feat? More, many more, than can be sent hither. The Southern people, in such a cause, would fight to the last, and when the men all fell, the women and children would snatch their arms and slay the oppressors. Without complete annihilation, it is the merest nonsense to suppose our property can be confiscated.

But if a forced reconstruction of the Union were consummated, does the North suppose any advantage would result to that section? In the Union we could not be compelled-to trade with them again. Nor would intercourse of any kind be re-established. Their ships would be destroyed, and their people could never come among us but at the risk of ill treatment. They could not maintain a standing army of half a million, and they could not disarm us in such an extensive territory.The best plan, the only plan, to redeem the past and enjoy blessings in the future, is to cease this bootless warfare and be the first to recognize our independence. We are exasperated with Europe, and like the old colonel in Bulwer’s play, we can like a brave foe after fighting him. Let the North do this, and we will trade with its people, I have no doubt, and a mutual respect will grow up in time, resulting, probably, in combinations against European powers in their enterprises against governments on this continent.