The following letter, though not a part of my journal, is occasionally referred to in it, and I therefore have it inserted here:—

Camp Near Belle Plaines, Virginia,

December, 10, 1862.

My Dear C—— :

* * * * Our whereabouts is four miles from Falmouth, three and a half from the mouth of the Potomac Creek, and about three to the nearest point of the Rappahannock River. As we may be ordered to leave here within an hour, that is sufficiently explicit. Although I have not hesitated at times to express my opinion, confidentially, of the conduct and merits of men, I rarely venture one prospectively, of military matters and strategy. As, however, you express so great a wish for my opinion on the prospects and plans of the war, I will tell you what I know of the present, and guess of the future state of things, reminding you that I am not a military man, and give but little of my attention to military affairs. The Medical Department occupies al my time.

One month ago to-day, our forward movements were arrested by General Burnside superceding McClellan, in the command of the army. We supposed that it would require at least a week or two for him to mature a plan of operations, and have the army mobilized; we were mistaken. Five days sufficed, and we were off like a quarter horse; but just as we arrived at the seat of operations, we were suddenly brought to a stand by the failure of somebody to furnish the supplies to enable us safely to cross the Rappahannock, and to take possession of the heights before the arrival of the enemy. We were consequently stationary, and he got possession of the ground we meant to occupy. Did we do right to stop? My partiality for and confidence in the opinions of General Burnside strongly incline me to think we did, whilst my own reasoning questions it. It seems to me, that we had at Falmouth, before the arrival of the enemy, a force sufficient to have taken the ground and held it till we should get the railroad from Acquia Creek, in order to transport supplies for the whole army, and then, for an object so important, we might have put our men on half rations, for a few days. The enemy, in all his campaigns, runs a heavier risk than that. Indeed, in one of his reports he speaks sneeringly of “the immense transportation trains, without which it seems impossible for the Yankees to move.” But there are doubtless many reasons which I cannot see. But the position is lost. What next?

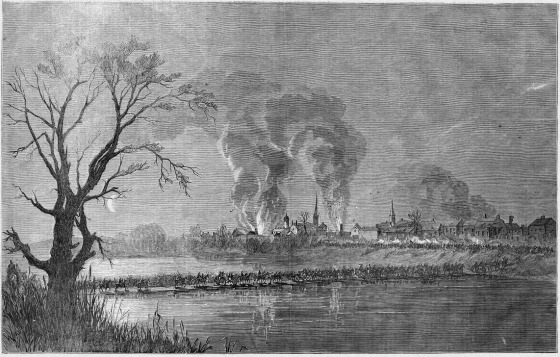

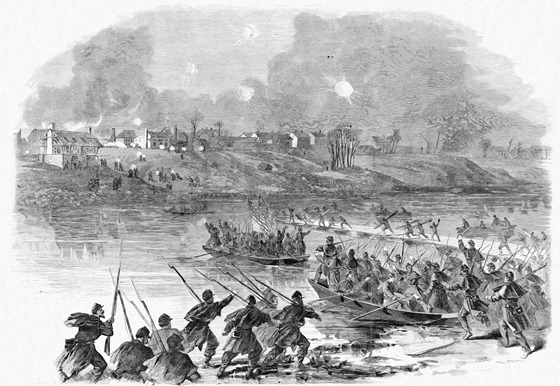

We must advance.—Public pressure will compel us to, against any odds. Yet we cannot advance without crossing the river. The enemy occupies all the heights, both front and enfilading, and with a force at least equal to our own, commands the crossings. Shall we risk it against such odds? In my opinion we must. But is this the only place to cross? Our pontoons are already in the river, some above, some below. An hour’s time will suffice to throw them into bridges, where we choose. Have we not ingenuity enough to draw attention by a feint at one point, whilst we bridge and cross at another. Should we cross either above or below, we shall occupy a flanking position with decided advantage. I think we shall cross, and I shall not be surprised if even before this letter is finished, we are summoned to attempt it. I think, too, that we shall cross without much resistance. What then?Will the enemy withdraw? Not an inch. He cannot fall back without disaster, and every foot of ground hence to Richmond, will be contested. For, give us Saxton’s Junction, twenty-five miles south of us, and Petersburg, which we can take when we want it, and Richmond is cut off from supplies, and must fall. I stop here to say that my prediction is already verified. Major B. has this moment left me an order to move at 2 in the morning. He says that in a council of war just held, it is decided to cross at three points at daylight. Shall we do this? I doubt it; and simply because it is the result of a council. It is too public. Burnside is not the man to send word to the enemy when he is coming. This, however, is all conjecture. The morning will tell how well grounded.

Yours, &c.