17th.—To this day I have lived fifty four years—cui bono? With all my defects in moral, mental and physical organization, I believe that in the aggregate of these powers, God has favored me, up to the average of men. Have I used those capabilities up to their power, for good? If asked positively, I do not hesitate to say, No! There have been many opportunities for me to do good, which I have not embraced, but if asked comparatively, I as unhesitatingly answer, Yes? No man is perfect, and few, I think, have struggled harder or more unselfishly to be useful and to alleviate the sufferings of others than I have. As, then, I have failed, by my own admission, to do all I could, but have satisfied my conscience, by striving to do better than others, shall I continue to be satisfied with this measure of my efforts? Can any man, with that alone as his guide, say and feel that he wholly divests himself of the motives of public approbation, and that there is not, after all, something of selfishness in his efforts. I fear that a close examination of this question, would, to my conscience, be less pleasant than profitable. Rivalry is a motive necessary to advancement, but unsupported, it is a weak staff on a long journey through a life of temptations. Support it, however, by a desire to live for other’s good, and the lame and the halt may lean on it with confidence and with comfort. God grant that for the short time remaining to me, I may have all these for my support, and that I may live more usefully than I have done.

..

“Teach me to feel another’s woe,

To hide the faults I see.”

..

Well, I am at a loss to judge what will be the next move in the great game now being played. I am two to three miles from the army, and being shut up in my hospital, I have less means of judging than if I were in Washington or Wisconsin. But how little, oh, how little, do our people at a distance from the scat of war realize of the sufferings it inflicts, say nothing of the abandonment of homes, where only the joys of childhood can be recalled in all their freshness, where the whole history of the family is written on the very walls and trees, to which we bid farewell forever, where little “tracks in the sand” constantly remind us of our deep but joyous responsibilities of directing little footsteps to good, to high, to holy walks, or where the little empty armchair chains us, through sad memories by a tie stronger even than that of our joys. Say nothing of the thousands of larger chairs made vacant, and the deep heart aches which they cause, still the sufferings, little, when compared with these, would strike terror to the minds of those who have not witnessed these scenes of distress.

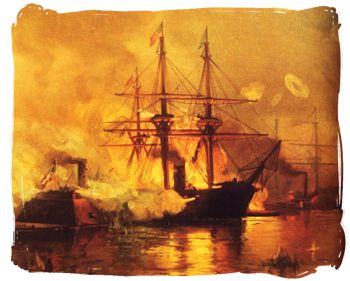

At a farm house, in the yard of which we have our medical headquarters, I met this morning a young lady of genteel appearance. I soon learned that she was from Fredericksburg. It was a cold morning. Rude soldiers, and officers not much more polite, regardless of the comforts of the household, had filled every space and had crowded her, with the rest, into the open air. Her teeth chattered from the cold. I invited her to my tent, in which was a good, warm stove. With a look of surprise, a little hesitation and a pleasant laugh at the novelty of the situation, she accepted my invitation. Having remained with her a few minutes, and obtained her promise to dine with me, I left her in the enjoyment of the warm stove. I found her highly educated, and a lady. Her father had died, leaving a handsome property in the city of Fredericksburg, the rents of which supported the family aristocratically. During the dinner, I made a laughing apology for offering her some sweet meats on a tin plate, with an iron spoon. The cord which she had held tense and tightly, now gave way. Dropping knife and fork, she exclaimed: “Oh, sir! excuse me. Two days ago this would have been palatable, though eaten on the trodden road, but now I cannot eat; five days of fasting and anxiety have destroyed even my power to hunger, and here I am a starving beggar, dependent even for shelter on the charity of the poor paralytic owner of this house, who has not a mouthful to feed himself, his wife and children. Oh! my poor, poor mother!” “May I know what of your mother, Miss G——?” “Four days ago I stood near you, as you watched from the river bank the shelling of our city, I witnessed the pleasure with which you noted the precision of the shot which fired the veranda of my mother’s house.[1] In that house I last saw her, ten days ago. Oh, my God, where is she to-day? Old and feeble, she could not get away!”

“But did you abandon her there?”

“When you ordered the evacuation of the city, within six hours, I was from home. I did not hear of it till the time had expired, and since I have been denied admittance to the city, and have had no means of learning how or where she is. Can not you, sir, procure me a pass through your lines?

She told me, too, of her sister, whose husband, a Colonel in the rebel army, was killed in battle two months ago. Three days after, her sister died of a broken heart, leaving in her charge an orphan child of two years; and this child, too, was left in the city, with its grandmother. How many years of civil life would it require to accumulate the misery historied in these dozen lines, intended only as an apology for a lady’s want of appetite? The misery of herself, the starvation of the paralytic and his large family, the deaths of the heart-broken sister and her husband, the orphanage of the child, and the destitution of the poor decriped mother! and not a tear did I shed at her distress. Did my benevolence owe a single tear to each case as bad as this, my whole life-current converted into tears, would never pay the debt; yet it is well to record a case, occasionally, that when I feel inclined to complain of my lot, it may serve to remind me of how much worse it might be.

After dinner, Surgeons and attendants were collected to dress the wounded, who were operated on four days ago. As I halted at the door of the tents containing the two hundred mangled men, I thought of the three-fifths of the amputations which had proved fatal, after the battle of Hanover. I pictured to my mind the two-fifths who had died within five days after the battle of Antietam, and I rallied all my fortitude to meet with composure the anxious dying looks of the poor fellows who had been jostled and dragged from place to place, for four days, and whose dependence on me had won for them my affections. Oh! who would be a Surgeon?

Before sun-down, all were dressed, and every man deposited in ambulances for general hospital, and except some four or five, wounded in organs which rendered them necessarily mortal, to our surprise, we found every wound doing well, every patient apparently recovering, and as we left them with a farewell, and heard the muttered prayers and benedictions of the poor sufferers, I found a tear to spare. Who would not be a Surgeon?

[1] I remember it well, and a beautiful house it was.