Monday, 9th—Moved up in five miles of Town.

Saturday, February 9, 2013

“I have advised my men to whip any enlisted man they hear talking copperheadism..,”–Army Life of an Illinois Soldier, Charles Wright Wills.

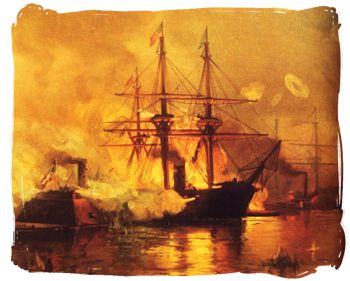

Ninth.—Papers of the 6th give me much pleasure. The dashing move of the ram “Queen of the West,” the gallant fight of our soldiers at Corinth, are certainly enough good news for one day. At noon roll call to-day, I spoke to my men of the resolutions passed by the officers at Corinth and approved by the soldiers, and told them that a chance would be offered them in a few days to vote on similar ones. They received the latter statement with a cheer that plainly showed their mind on the subject. I believe that the whole regiment with a proper action of the officers for a few days, will denounce copperheadism, even in terms strong enough to suit the Chicago Tribune. ‘Twill be the officers fault if we don’t. If we were only officered properly throughout there would never have been a word of dissatisfaction in the regiment. That is rather a solemn subject. I have advised my men to whip any enlisted man they hear talking copperheadism, if they are able, and at all hazards to try it, and if I hear any officer talking it that I think I can’t whale, I’m going to prefer charges against him. Doing plenty of duty now; on picket every other day. Last night I had command of a guard at General Hospital No. 1, or rather we guarded it in the day time, relieved at 9 p.m. and went on again at daylight. I had some friends in the hospital, steward, warden and clerks, and they made it very pleasant for me. That is they fed me on sanitary cake, butter, etc., induced me to drink some sanitary wine, beer, etc., and also to sleep between sanitary sheets, with my head on a sanitary pillow, etc., and again this morning to accept a bottle of sanitary brandy and a couple of bottles of sanitary porter. All of which I did, knowing that I was sinning. I write you this that you may feel you are doing your country some good in forwarding the above articles for the benefit of the soldiers. You will of course, give these encouraging items to your coworkers.

Pilot Town, Feb. 9th. We have been lying to anchor here for over two days, for the reason that there has not been sufficient depth of water on the bar to admit of our crossing. At eleven thirty A. M., pilot came on board and reported water enough. At noon, got under way and steamed down. Unfortunately for us, in attempting to cross the bar at South-West Pass we ran the ship hard aground.

Monday, February 9th, 1863. Night.

A letter from my dear little Jimmy! How glad I am, words could not express. This is the first since he arrived in England, and now we know what has become of him at last. While awaiting the completion of the ironclad gunboat to which he has been appointed, like a trump he has put himself to school, and studies hard, which is evident from the great improvement he already exhibits in his letter. . . .

My delight at hearing from Jimmy is overcast by the bad news Lilly sends of mother’s health. I have been unhappy about her for a long while; her health has been wretched for three months; so bad, that during all my long illness she has never been with me after the third day. I was never separated from mother for so long before; and I am homesick, and heartsick about her. Only twenty miles apart, and she with a shocking bone felon in her hand and that dreadful cough, unable to come to me, whilst I am lying helpless here, as unable to get to her. I feel right desperate about it. This evening Lilly writes of her having chills and fevers, and looking very, very badly. So Miriam started off instantly to see her. My poor mother! She will die if she stays in Clinton, I know she will!

February 9—We established a regular camp here. This last march has been a very hard one, and only a distance of thirty miles. But it took us from Wednesday to Saturday, through snow, rain and mud ankle-deep and without rations. Kinston is a perfect ruin, as the Yankees have destroyed everything they could barely touch, but it must at one time have been a very pretty town—but now nothing scarcely but chimneys are left to show how the Yankees are trying to reconstruct the Union.

February 9, Monday. A special messenger from Admiral Du Pont with dispatches came to my house early this morning before I was awake, and would deliver them into no hand but my own. I received them at the door of my chamber. They relate to the late flurry at Charleston. The Mercedita was neither captured nor sunk, nor was any vessel of the Squadron. The Mercedita and Keystone State were injured in their steam-chests, and went to Port Royal for repairs. All the noise about raising the blockade was mere trash of the Rebels South and their sympathizers North. Dr. Bacon, the bearer of the dispatches, came to Philadelphia in the prize Princess Royal, captured running the blockade. Abuse will cease for a day, perhaps, under this intelligence. Am surprised at the ignorance which prevails in regard to the principles of blockade, which the late trouble has exposed.

From Colonel Lyon’s Letters.

Feb. 9, 1863.—There is a report that Van Dorn is advancing upon us from the southwest with a large force, which may be true. Many of the rebel army are in a starving condition. It was for that reason they were so anxious to get in here.

The weather is very warm, with lots of mud. We are doing some work on fortifications and giving the rebels some chance to do us a good turn if they choose to give us a call. If we are attacked here at any time we shall put the women on a steamer and send them a few miles down the river.

9th. In the morning moved up to the commissary to make room for Lt. and Mrs. Abbey and child. Brougham came and I went to town with him in the evening. A lunch in town and then to Melissa’s. Major P. and Reeve left for Kentucky. Met Brougham at 10 at Winard’s and went to Mr. Crarey’s for the night.

Monday, 9th—We left for Lake Providence, seventy-five miles above Vicksburg, at 10 o’clock this morning, and reached our destination at dark. There were six transports and one gunboat in our fleet. We found the First Brigade of our division already here and at work cutting the levee.

February 9th [1863]. Reported seizure of the arsenal by Governor Seymour, of New York. Probable seizure of Lincoln. I don’t believe these reports. The old Democratic party is indeed aroused, but it is a law-abiding party, and I do not think we can expect of it any violent proceedings. They are disgusted with Lincoln, but they helped to elect him and must tolerate him. Banks has been warned by his Government that he is to be lenient to us. He has done nothing for us, but he has committed none of Butler’s enormities. He does not give up seized houses, but they say rent is to be given by those occupied by Government officers; however, nobody expects the payment. He does not encourage tale-bearing of negroes, and has had no one arrested for opinion’s sake, but he has had none of the innocent, imprisoned by Butler, released. I have heard that he speaks often unkindly to ladies who go to him begging for their husbands or friends to be released. “My husband will die, sir, his health is so bad, and my relative has lost his mind in confinement,” said one lady to him. “We must all die, madam,” he returned; “prison life affects men differently; some lose their minds and some die; this we cannot help.” Poor Mrs. Harrison has been wearying herself for months in behalf of her husband who has been confined in the Custom House without comforts and with many others in the same room—offence, as far as it can be made out, trying to save the property of a “rebel” friend, Captain Dameron, formerly a Confederate Guard. The three Episcopal ministers, Mr. Fulton, Mr. Goodrich, and Doctor Leacock, arrived here last week. They were sent off by Butler for not praying for the President of the United States. They were well received in New York by people of secession tendencies there; were treated with great kindness and were invited to preach in the churches. All reasonable people, all indeed, except fanatics, cried “Shame!” on the treatment these divines had received in New Orleans. Banks having arrived here and there being no probability of Butler’s return, these three ministers have ventured hither.

They were not allowed to land because they had not taken, and would not take, the oath of allegiance to the United States Government. This proceeding caused great excitement and many persons have visited the boat, the Cromwell, in which they are imprisoned. They were transferred to the McClellan and reshipped to New York after being refused even one visit to their homes, or a simple walk on the shore they loved so well. No Episcopal minister dishonored himself here by taking the oath to a Government he had abjured. Seven resisted, though these three only were sent off. If Butler had remained, others would have suffered, as they had been ordered to hold themselves in readiness. Last summer when they were first threatened and the excitement of the people on the subject was discussed, I could not help thinking of the trial of the “Seven Bishops”—”the Seven Candlesticks.” How history repeats itself in spite of the progression of our race. Sarah Erwin, now Mrs. Doctor Glen, was in Doctor Goodrich’s church last fall when Colonel Strong dispersed the congregation. Never had she thought to witness such a scene. Before the time had come for praying for the President of the United States, or the time for the omission rather, Colonel Strong, who had been mistaken by the congregation for one of our own people, arose and whispered something in Mr. Goodrich’s ear. Colonel Strong, Butler’s agent, was very pale and much excited, and as he was wrapped in a cloak which covered his military dress he was thought some mourner who had requested the prayers of the minister. He had appeared so nervous and so depressed and so deathly pale that he had excited the sympathy of the people; great was the surprise, therefore, when he arose and in the name of the Government of the United States forbade the ceremonies of the church to proceed, and ordered the congregation to disperse.

There was an immediate uprising of the people and a rush to the pulpit; the first thought was that Doctor Goodrich was in danger. No one was safe from arrest in Butler’s time. Women wept and men muttered and I am told that even oaths were heard; some women who had always been considered timid and gentle, openly defied Strong and denounced him to his face. Strong threw off his cloak and this gave a full view not only of his elaborately wrought regimentals, but also of a goodly show of side arms. The sight of glistening steel and pistols in that peaceful assembly neither calmed nor awed it. Many became infuriated and women especially clustered around Strong to his evident fear. One old lady called down a curse upon him and all he held dear. All thought it a proper place, perhaps, in which to open those vials of wrath, the existence of which the church warrants. Pale but firm, Doctor Goodrich asked permission at least to give his blessing to the congregation. “No,” cried the brute Strong, “I forbit it.” “My people,” returned Doctor Goodrich, “shall not depart without my benediction.” He then made a few remarks that filled the building with hysterical sobs. After the people had left church, they were again ordered to disperse, and at the very door a Federal asked of Colonel Strong permission to send for the artillery. “You had better order up a gunboat, sir, as that seems to be your only safeguard,” returned an excited young woman, said to be a Jewess. An old lady made protest by saying that she had as good a right as Butler himself to stand upon the banquette and that she would return home in her own time. It was the most disgraceful scene. It is said that Butler was gazing with the aid of a glass from his own window; he had not then stolen Mrs. Campbell’s house and was residing in General Twiggs’, and was reported to have been highly amused, but his adjutant, Colonel Strong, remarked that he would rather go to battle than to go through the same excitement again. Doctor Goodrich was arrested some time after this event and has been in New York some months. When he will be able to return to his anxious wife after this second exile, Heaven only knows. Mrs. Goodrich is supported by contributions from her husband’s flock; they are not able to do as much as they wish for her as all fortunes are in a state of ruin now. Servants have run or have been taken away from plantations, houses burned, banks robbed, and all business suspended; lawyers cannot practice and no one can sell a piece of property without first having taken the oath to the United States Government.

Some time ago there was a report here that the Alabama, or 290, after destroying the United States steamer Hatteras had appeared at the mouth of this river; that pilots had gone on board of her and that Captain Semmes had sent by them a challenge to Farragut to come down in his flagship and fight him. It is believed, and the pilots were said to have been imprisoned upon their return because they had taken the oath to the Confederacy on board the 290. Farragut did not go, but the Mississippiwas sent down in great haste under some other pretense. It was said that the Oreta or Florida, Captain Maffet, was also at the Balize. Those taken prisoner by these two Captains report them gentlemen; they treat their captives in a different manner to that in which the Yankees treat ours. Captain Maffet is a small, slight man, very timid, blushes like a girl when he attracts notice, looks like a poet, and is, from the prisoners’ report, a gentleman, every inch of him. Mr. Fulton has had a call to a church at Snow Hill, Md.; he has been told that he need not pray for the President of the United States there; don’t know that he will accept it, has no support. Our churches here are open, but I have not attended; our regular ministers do not officiate. In our little Calvary church Mr. Lyons reads a written sermon and goes through the service. Rose Wilkinson attempted to play the melodeon and attended three or four singing meetings for that purpose, but Mr. Payne, a pompous Englishman, who has made a great deal of money here, was so rude on account of a few mistakes, which were the consequence of her timidity, that she declined going any more. Mr. Tucker, one of our gentlemen, whose ear is quite as good, bore with her kindly and politely. Mr. Payne has since had almost a contention with a Mrs. Hedges, a Scotch lady, who has taken Rosa’s place; she sings songs and ballads sweetly and with much taste, but does not sing church music correctly, they say. Mr. Payne says so. He doesn’t look as though he had an ear, it was a great mistake in nature to have given him one. I should like to tell how disagreeable and pompous he is; if he were not rich he would be afraid to express an opinion, so I think of him.