February 15th, 1863.

We are now on the “heaving sea and the bounding wave.” We were aroused yesterday morning at four o’clock, ordered to prepare breakfast and be ready to march at a minute’s notice. At five-thirty the bugle sounded “fall in.” We slung our accoutrements, the first time since the battle of Fredericksburg, and in fifteen minutes were en route to the depot, distance about two miles. After some delay we took cars for Aquia Creek, where we arrived at 10 o’clock a. m., and were immediately transferred to transports, bound for Fortress Monroe. The Seventy-ninth New York and Seventeenth Michigan were crowded on the North America, an old Hudson River propeller. There was hardly standing room, much less room to walk about. The day is fine, and the bay, unruffled by a breeze, presents a lively and picturesque appearance. Steamers are continually arriving and departing, sailboats of all sorts and sizes spread their white wings and glide leisurely through the still waters, while the active little tugs go whisking and snorting here and there, assisting larger and more unwieldly vessels. We left Aquia Creek at 10:30 o’clock a. m., expecting to reach the Fortress by nine o’clock next morning. I love the sea in all its forms and phases, and it was with a thrill of joy I took my seat on deck, prepared to enjoy whatever of interest might present itself. The Potomac, at Aquia Creek, is truly a noble stream, if stream it may be called, for there is no perceptible current, being, I judge, one and one-half miles wide, gradually broadening out as it nears the bay, until at its mouth it is nine miles wide. There is a striking contrast between the Maryland and Virginia shores. The Virginia side, nearly the entire distance, presents a rugged, mountainous aspect, with very few buildings in view, while the Maryland shore is level, dotted with farm buildings, and, at frequent intervals a village with its church spires glittering in the sun. In contemplating these peaceful scenes of rural life, the quiet farm houses surrounded by groves of trees, the well-tilled fields, outbuildings and fences undisturbed by war’s desolating hand, the genial air of quiet repose that pervades the scene calls up emotions that have long lain dormant. For many long months, which seems as many years, my eyes have become inured to scenes of blood, of desolation and of ruin; to cities and villages laid waste and pillaged; private residences destroyed; homes made desolate; in fact, the whole country through which we have passed, except part of Maryland, has become through war’s desolating touch, a desert waste. As I gazed on these peaceful scenes and my thirsty soul drank in their beauty, how hateful did war appear, and I prayed the time might soon come when “Nations shall learn war no more.”

Gradually the wind freshened, increasing in force as we neared the bay, until it became so rough the captain thought it unsafe to venture out, and cast anchor about five miles from the mouth of the river to await the coming of day. I spread my blanket on the floor of one of the little cabins and slept soundly until morning. When I awoke in the morning the first gray streaks of early dawn were illuminating the eastern horizon.

The gale having subsided, we were soon under way, and in about half an hour entered the broad Chesapeake. And here a scene most grand and imposing met my enraptured gaze. Not a breath of air disturbed its unruffled surface. Numerous vessels, floating upon its bosom, were reflected as by a mirror. A delegation of porpoises met us at the entrance to welcome us to their domain; they were twenty-two in number, were from six to eight feet in length; in color, dark brown. It was truly amusing to witness their sportive antics as they seemed to roll themselves along. They would throw themselves head foremost from the water half their length, turning as on a pivot, perform what seemed to be a somersault, and disappear.

A flock of sea gulls fell into our wake, sagely picking up any crumbs of bread that might be thrown them. They are a strange bird, a little larger than a dove, closely resembling them in color and gracefulness of motion. They followed us the whole distance, and as I watched their continuous, ceaseless flight, the effect on the mind was a sense of weariness at thought of the long-continued exertion.

Soon after we entered the bay I observed what I thought to be a light fog arising in the southeast. We had not proceeded far, however, before I discovered my mistake, for that which seemed to be a fog was a shower of rain. I was taken wholly by surprise, for I had been accustomed to see some preparation and ceremony on similar occasions. But now no gathering clouds darkened the distant sky, warning me of its approach, but the very storm itself seemed to float upon the waves and become part of it, and before I was aware, enfolded us in its watery embrace. The storm soon passed, but the wind continued through the day, and, as we neared the old Atlantic and met his heavy swells, they produced a feeling of buoyancy that was, to me, truly exhilerating.

Some of the boys were seasick, and a number “cast up their accounts” in earnest. We entered the harbor about sundown and cast anchor for the night under the frowning guns of Fortress Monroe.

Vessels of war of every class, monitors included, and sailing vessels of all sizes, crowded the harbor. It was a magnificent scene, and one on which I had always longed to gaze.

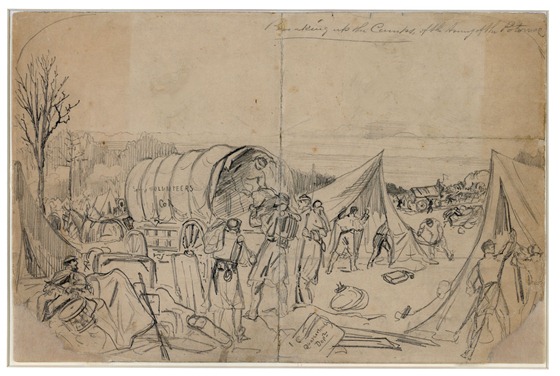

In the morning we learned our destination was Newport News, distant about five miles. We arrived about eight o’clock, marched two miles to Hampton Roads, our camping ground, pitched tents and, at noon, were ready for our dinner of coffee and hardtack.

We have a pleasant camping ground, lying on the beach, where we can watch the vessels as they pass and can pick up oysters by the bushel when the tide is out.