Friday, 20th.—”Queen of the West” reported captured by our little fleet from the mouth of Red River.

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

Washington Friday Feb. 20th 1863.

Rather a dull day in the office there being but little to do on the Examining Board. I have spent most of the day reading old Saml Pepys Diary written two hundred years ago during Charles 2nds reign. It gives a not very flattering picture of English society at that time. In looking at that age and then at the present, any one must acknowledge that great progress has been made in the morals of refined Society. One is surprised at the conduct which was tolerated in that day, especialy in and around the Court. Pepys himself occupied a responsible position under the Crown, something nearly equivalent to the Sec’y of our Navy. The old Villin was constantly accepting bribes for he notes down all He did and all his thoughts from day to day. He casts up his accounts at the end of every month and piously blesses God that he is getting on in the world so well, the hypocrite, full of pride and vanity and an ardent admirer of the Ladies. I am not through with him yet. There is no news today worthy of note. The French have invaded Mexico and from all accounts are getting roughly handled there. It is thought by many that we will be at War with France soon. Most assuredly we shall if she intervenes in our war with the south or acknowledges its Independance. I have spent most of the evening over to Charleys (or the Doctors) as he is called. Played a game of chess with him, in my room at 10.

From Colonel Lyon’s Letters.

Feb. 20, 1863.—Night before last I had information leading me to believe that an attack here was quite probable, and as a measure of precaution I had all the women pack their trunks and get ready to ‘vamose the ranch,’ at double quick if necessary. We were up most of the night. We were misled by the telegraph operator at Fort Donelson. In the morning all was explained and we resumed our usual equanimity. Colonel Lowe is absent, and the whole responsibility in case of an attack here is on me.

A very heavy wind last evening made our tent and Adelia’s nerves shake considerable, but I made everything right by holding down the tent pole.

“Four of my brigade have been sentenced to be shot—three for desertion and one for cowardice.”–Letters from Elisha Franklin Paxton.

Camp Winder, February 20, 1863.

I have been improving since I got back to camp, and now begin to feel that I am quite well. I trust that it may continue, for during the last six months I have suffered much from the fact that I have seldom been very well.

Until this morning we had snow and rain continually since I returned. This is a bright, clear morning with a strong wind, which I think will soon dry the ground. As it is now, the roads are so muddy that it is next to impossible to get provisions for our men or feed for our horses. Since I reached camp I have been quite busy. The day before yesterday I wrote eight pages of foolscap paper, more than I have written in one day for the last two years. I sometimes think if my health were good my eyes would give me no trouble.

There is an impression that a large part of the force which was in front of us has moved. If so, it indicates that we, too, before many days may move, and that there will be no more fighting on the Rappahannock. In three or four weeks we will have spring weather, and then we may expect employment. Where we will be in a month hence, God alone knows. Some of our troops have already moved, but their destination is not known. It is a business of strange uncertainties which we follow. For my part, I have gotten used to it,—used to it as an affliction with which despair and necessity have made me contented. I used to look upon death as an event incident only to old age and the infirmities of disease. But in this business I have gotten used to it as an every-day occurrence to strong and healthy men, some upon the battlefield and others by the muskets of their comrades. Four of my brigade have been sentenced to be shot—three for desertion and one for cowardice. It is a sad spectacle, and I sincerely wish that their lives might have been spared. I trust that God in his mercy may soon grant us a safe deliverance from this bloody business. Such spectacles witnessed in the quiet of the camp are more shocking than the scenes of carnage upon the battle-field. I am sick of such horrors. If I am ever blessed with the peace and quiet of home again, oppression and wrong must be severe, indeed, if I am not in favor of submission rather than another appeal to arms. I came away from home without your miniature; send it to me.

20th. Brought up the rations from town. Got another volume of Irving. Met Capt. when coming back. Expecting Sarah Jewell. Oberlin boys came back over their furloughs one day. In the evening read till late.

February 20th [1863]. Mary Harrison came to ask us to go with her to Mrs. Payne’s and thence to see the prisoners off. We did not feel like standing so long in such a crowd, though anxious to wave a handkerchief to them, too. Mary promised to come back to dinner, but Mrs. Dameron sent us an invitation to dine while Mary was here, so she declined coming back. We spent the day at Mrs. D——’s. Had quite a discussion about spiritualism. I don’t like to hear people say a thing can’t be true, or that it is not true and that they know it isn’t. I said that I felt too ignorant of nature’s mysteries to say what was or what was not true. Our being is so mysterious and the laws which govern it are so mysterious that I do not know how many other mysteries I may be involved in. I said that I was sure of one thing and that was that nothing but truth could live; false doctrine must die out, but truth can be crushed out only for a season. An abiding law of the universe must be abiding and revealed sometime. I am determined to be prejudiced against nothing but ignorance. Most people show so little sign of having thought at all except in commonplace, everyday matters, that it is a relief to be entertained with a beautiful fancy logically sustained as Mrs. Waugh sustains hers.

Sent for by Mrs. D—— on account of company at home; found Mrs. Wells, Mrs. Roselius and Mrs. Gilmour. Annie Waugh came in afterwards. Mrs. Wells tired out, having been running from one Federal ruler to another for days trying to get permission to send her young daughters in the Confederacy a few necessaries—no success after all her trouble. These people never say no at first. The Queen of the West, or, some say, the Conestoga, passed Vicksburg some time ago; she has captured three Confederate vessels with provisions, and has entirely cut off communication by water between Port Hudson and Vicksburg. Our Red River supplies and those from Texas also cut off. She must be sunk or captured. I expect to hear of one or the other in a few days. I read a speech of Wendell Phillips. No Jacobin of France, not even Robespierre, ever made so infamous a one. He says an aristocracy like that of the South has never been gotten rid of except by the sacrifice of one generation; they can never have peace, he says, until “every slaveholder is either killed or exiled.” He does not approve of battles—the negro should be turned loose and incited to rise and slay. “They know by instinct the whole programme of what they have to do,” he says. I at first blamed our secession, but our politicians knew these awful people better than I did and now I am glad that we are, or will, be rid of them.

Friday, 20th—There is some talk of our having to move our camp again. News came that our gunboats were throwing shells into Vicksburg, one every fifteen minutes, driving the rebels back, and that our mortar boats were damaging some of their water batteries.

Memphis, Friday, Feb. 20. Health better but very sore throat. Beautiful day.

20th.—A letter this morning from Sister M., who has returned to her home on the Potomac. She gives me an account of many “excitements” to which they are exposed from the landing of Yankees, and the pleasure they take in receiving and entertaining Marylanders coming over to join us, and others who go to their house to “bide their time” for running the blockade to Maryland. “Among others,” she says, “we have lately been honoured by two sprigs of English nobility, the Marquis of Hastings and Colonel Leslie of the British army. The Marquis is the future Duke of Devonshire. They only spent the evening, as they hoped to cross the river last night. They are gentlemanly men, having no airs about them; but ‘my lord’ is excessively awkward. They don’t compare at all in ease or elegance of manner or appearance with our educated men of the South. They wore travelling suits of very coarse cloth—a kind of pea-jacket, such as sailors wear. As it was raining, the boots of the Colonel were worn over his pantaloons. They were extremely tall, and might have passed very well at first sight for Western wagoners! We have also had the Rev. Dr. Joseph Wilmer with us for some days. He is going to Europe, and came down with a party, the Englishmen included, to cross the river. The Doctor is too High Church for my views, but exceedingly agreeable, and an elegant gentleman. They crossed safely last night, and are now en route for New York, where they hope to take the steamer on Wednesday next.” She does not finish her letter until the 17th, and gives an account of a pillaging raid through her neighbourhood. She writes on the 14th: “There had been rumours of Yankees for some days, and this morning they came in good earnest. They took our carriage horses, and two others, in spite of our remonstrances; demanded the key of the meat-house, and took as many of our sugar-cured hams as they wanted; to-night they broke open our barn, and fed their horses, and are even now prowling around the servants’ houses in search of eggs, poultry, etc. They have taken many prisoners, and all the horses they could find in the neighbourhood. We have a rumour that an infantry force is coming up from Heathsville, where they landed yesterday. We now see many camp-fires, and what we suppose to be a picket-fire, between this and the Rectory. My daughters, children and myself are here alone; not a man in the house. Our trust is in God. We pray not only that we may be delivered from our enemies, but from the fear of them. It requires much firmness to face the creatures, and to talk with them. The Eighth New York is the regiment with which we are cursed. The officers are polite enough, but are determined to steal every thing they fancy.” On the 15th she says: “This morning our enemies took their departure, promising to return in a few days. They visited our stable again, and took our little mare ‘Virginia.’ The servants behaved remarkably well, though they were told again and again that they were free.” Again, on the 17th, she writes: “I saw many of the neighbours yesterday, and compared losses. We are all pretty severely pillaged. The infantry regiment from Heathsville took their departure on Sunday morning, in the ‘Alice Price,’ stopped at Bushfield, and about twelve took breakfast there. Mr. B. says the vessel was loaded with plunder, and many negroes. They took off all the negroes from the Mantua estate; broke up the beautiful furniture at Summerfield, and committed depredations everywhere. A company of them came up as far as Cary’s on Saturday evening, and met the cavalry. They stole horses enough on their way to be pretty well mounted. They will blazon forth this invasion of a country of women, children, and old men, as a brilliant feat! Now that they are gone, we breathe more freely, but for how long a time?” We feel very anxious about our friends between the Rappahannock and Potomac, both rivers filled with belligerent vessels; but they have not yet suffered at all, when compared with the lower Valley, the Piedmont country, poor old Fairfax, the country around Richmond, the Peninsula; and, indeed, wherever the Yankee army has been, it has left desolation, behind it, and there is utter terror and dismay during its presence.

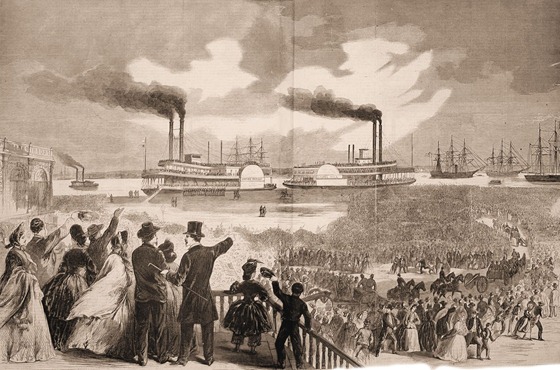

Scene on the Levee at New Orleans on the Departure of the Paroled Rebel Prisoners, February 20, 1863 – Sketched by Mr. Hamilton.

__________

EXTRAORDINARY EXCITEMENT IN NEW ORLEANS.

A VERY extraordinary exhibition of public feeling took place in New Orleans on Friday the 20th ult., which threw the whole city in the wildest excitement; but was, fortunately, attended with no serious consequences. We illustrate the scene on pages 184 and 185.

It having been publicly announced that a flag-of-truce boat would leave on Friday to convey some 382 paroled prisoners to Baton Rouge, and there exchange them on board a rebel vessel for Port Hudson, an immense concourse of the disloyal portion of the community congregated on the levee to see them go off. The Empire Parish, with the prisoners on board, was lying at the foot of Canal Street, and the Laurel Hill—moored immediately ahead of her—was selected by about 1000 at least, who crowded into and upon every part of her, to see the rebel prisoners and cheer them.

The Empire Parish had been advertised to leave at three o’clock, and it must have been as early as noon that the masses commenced to assemble. By two o’clock the whole levee, in its enormous width and extending all the way from Canal to Julia Street, was one dense sea of human heads; a large proportion of them females wearing secesh badges, and many openly waving little rebel flags—an insult not confined to their sex alone.

Seeing that matters were assuming a disgraceful if not alarming aspect, notice was sent to General Bowen, advising him of the fact, and suggesting the necessity of sending down some troops. The order was at once given, and soon a squad of the Twenty-sixth Massachusetts were on the ground, and a portion of a battery came threading its way through the crowd.

The scene at his moment was grand and exciting. The immense crowds on the levee swaying back by the advance of the soldiery—the Laurel Hill and the Empire Parish both one living mass of human beings cheering vociferously—and the balconies and windows facing the river teeming in every available spot, even to the roofs—the females screaming and waving their handkerchiefs, scarfs, flags, and parasols.

The order being given, the soldiers began to make the crowd move back; a delicate task not easy to effect, as the women were all in front, thus screening the men behind an impassable and invincible barrier of crinoline. The soldiers, however, behaved with perfect order, temper, and decency, making no reply to the insulting taunts from hundreds of the weaker sex, but, holding their muskets horizontally, gently made the crowd fall back. The balconies were also cleared of all their demonstrative occupants, and thus at last the whole mass was grumblingly dispersed, and the Empire Parish had to crawl off quietly in the night without that grand parting scene which the rebels evidently expected, and which the scene in the morning clearly promised. Upon the whole, it was a disgraceful and dangerous exhibition, and one which certainly ought to have been, and could have been, prevented had any ordinary means been used for avoiding its occurrence.