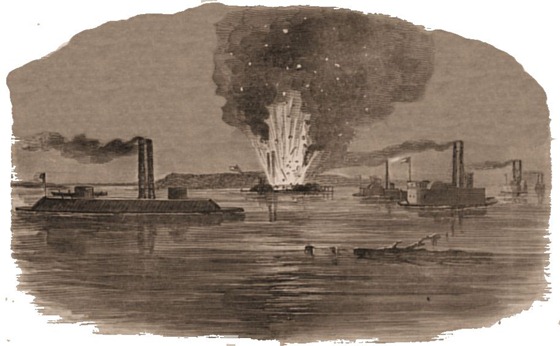

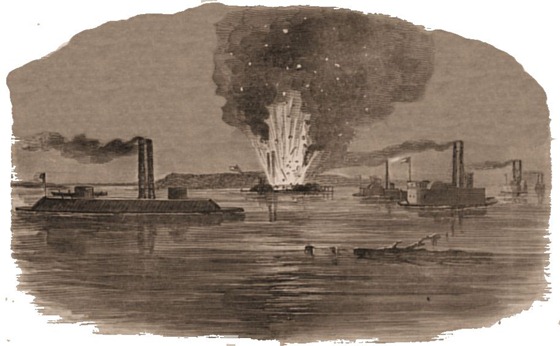

“Bache’s Quaker” Driving the “Queen of the West,” and Causing the Rebels to Blow up the “Indianola.”—[Sketched by Mr. Theodore R. Davis.]

BACHE’S QUAKER.

WE illustrate herewith the exploit of “BACHE’S QUAKER” on the Mississippi, at which the whole West is shaking its sides with laughter. After the loss of the Indianola, it seems, Admiral Porter and his officers were at their wit’s-end for some device to repair the loss. The Herald correspondent says:

On the 27th of February Admiral Porter dispatched what was called a paddy boat, or dummy Monitor, to run the Vicksburg batteries, in order to ascertain their exact location. This contrivance was an old flat-boat, with flour-barrels for smoke-stacks, and a couple of large hogs-heads to represent Monitor turrets. It ran the fortifications in gallant style, and drew the fire of the rebel guns, but, as far as could be ascertained, received no damage. The paddy boat, it seems, frightened the rebels, who were at work trying to raise the Indianola, below Vicksburg, and caused them to skedaddle on the double-quick. When they got safe away from what they supposed to be a turreted monster, or “a cheese box on a raft,” they reported the fact to their friends, and blew up the Indianola, to prevent her from again falling into the hands of the Yankees.

In reference to this the Jackson Mississippian had the following:

The destruction of the Indianola was a most unnecessary and unfortunate affair. The turreted monster proved to be a flat-boat, with sundry fixtures to create deception. She passed Vicksburg Tuesday night, and the officers believing she was really a turreted monster, blew the Indianola up, but the guns fell into the hands of the enemy.

The Vicksburg Whig of 5th says:

We stated a day or two since that we would not enlighten our readers in regard to a matter which was puzzling them very much. We alluded to the loss of the gun-boat Indianola, recently captured from the enemy. We were loath to acknowledge she had been destroyed, but such is the case. The Yankee barge sent down the river last week was reported to be an iron-clad gun-boat. The authorities, thinking that this monster would retake the Indianola, immediately issued an order to blow her up. The order was sent down by courier to the officer in charge of the vessel. A few hours afterward another order was sent down countermanding the first, it being ascertained that the monstrous craft was only a coal-boat; but before it reached the Indianola she had been blown to atoms — not even a gun was saved. Who is to blame for this folly, this precipitancy? It would really seem as if we had no use for gun-boats on the Mississippi, as a coal-barge is magnified into a monster, and our authorities immediately order a boat that would have been worth a small army to us to be blown up.

The New York Times publishes a letter from an officer, from which we extract the following:

Finding that they (the rebels) could not be provoked to fire without an object, I thought of getting up an imitation Monitor. Ericsson saved the country with an iron one — why could I not save it with a wooden one? An old coal-barge, picked up in the river, was the foundation to build on. It was built of old boards in twelve hours, with pork barrels on top of each other for smoke-stacks, and two old canoes for quarter-boats; her furnaces were built of mud, and only intended to make black smoke and not steam.

Without knowing that Brown was in peril, I let loose our Monitor. When it was descried by the dim light of the morn, never did the batteries of Vicksburg open with such a din; the earth fairly trembled, and the shot flew thick around the devoted Monitor. But she ran safely past all the batteries, though under fire for an hour, and drifted down to the lower mouth of the canal. She was a much better looking vessel than the Indianola.

When it was broad daylight they opened on her again with all the guns they could bring to bear without a shot hitting her to do any harm, because they did not make her settle in the water, though going in at one side and out at another. She was already full of water. The soldiers of our army shouted and laughed like mad, but the laugh was somewhat against them when they subsequently discovered the Queen of the West lying at the wharf at Warrenton. The question was asked, what had happened to the Indianola? Had the two rams sunk her or captured her in the engagement we heard the night before? The sounds of cannon had receded down the river, which led us to believe that Brown was chasing the Webb, and that the Queen had got up past him.

One or two soldiers got the Monitor out in the stream again, and let her go down on the ram Queen. All the forts commenced firing and signaling, and as the Monitor approached the Queen she turned tail and ran down river as fast as she could go, the Monitor after her, making all the speed that was given her by a five-knot current. The forts at Warrenton fired bravely and rapidly, but the Monitor did not return the fire with her wooden guns, but proceeded down after the Queen of the West. An hour after this the same heavy firing that we had heard the night before came booming up on the still air.

This “booming” was the destruction of the Indianola.

The following is Admiral Porter’s official account of the affair:

U. S. MISSISSIPPI SQUADRON, YAZOO RIVER,

March 10, via MEMPHIS AND LOUISVILLE, 13th.

Hon. Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy: I have been pretty well assured for some time past that the Indianola had been blown up, in consequence of the appearance of a wooden imitation mortar, which the enemy sunk with their batteries. The mortar was a valuable aid to us. It forced away the Queen of the West, and caused the blowing up of the Indianola. D. D. PORTER.

The Richmond Examiner, in a very grim way, thus pokes its fun at the rebels:

The reported fate of the Indianola is even more disgraceful than farcical. Here was perhaps the finest iron-clad in the Western waters, captured after a heroic struggle, rapidly repaired, and destined to join the Queen of the West in a series of victories. Next we hear that she was of necessity blown up, in the true Merrimac-Mallory style—and why? Laugh and hold your sides, lest you die of a surfeit of derision, O Yankeedom! Blown up because, forsooth, a flat-boat, or mud-scow, with a small house taken from the back-garden of a plantation, put on top of it, is floated down the river, before the frightened eyes of the Partisan Rangers. A turreted monster!

________________

Harper’s Weekly, March 28, 1863