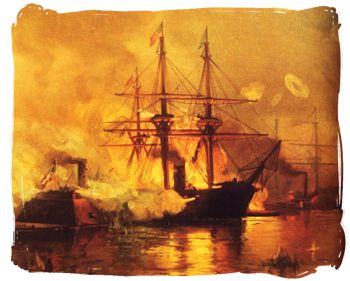

April 7th. I have been quite sick, and am still too weak to write and sew much; so depressed in spirits that I find no diversion in anything. Within the last week the great Yazoo expedition has been abandoned; so also has the Port Hudson one. What Banks has done so far can not aid his infamous Government much. A few days ago the paroled prisoners in town received a notice to appear before a certain person at a given hour, or be fetched by the military. They obeyed the order, not knowing what was to become of them, whereupon they were locked up in the Custom House and sent off to be exchanged secretly, so that no crowd could collect and see them off. They left at night, and spite of secret movements, some knew of them and would at least appear upon the levee, though they dared make no demonstration in favor of the Confederate cause. One gentleman waved his hat to the departing boat and was immediately arrested. He proved to be a Scotchman, and nothing could be done to him. Ladies are constantly arrested for the color of the roses they wear on their bosoms and bonnets. Alas! for handkerchiefs bearing the Confederate flag! One of the paroled prisoners about to depart was presented with two roses by a lady—one red and the other white; he placed them in his button-hole, and the defiant exhibition caused his arrest and return. He was Lieutenant Musselman, and he was much disappointed at not being able to go with his companions beyond the lines. A flag of truce boat arrived here, but none of our people were allowed to put foot on the shore or to receive their friends on the boat. Mrs. Shute, who has been separated from her son for two years, went down to the levee to try to get a glimpse of him. She was denied the privilege of even standing on the shore and even getting a far-off glance at him. She went to each authority in town, begging the privilege of seeing him but for a moment or two on board the boat, but was refused.

There has never been such great and small tyrannies practised in the world before, I verily believe, as by those who now conduct the affairs of this city. A lady can not give a party in her own home without she receives a permit from some such creature as Captain Miller, or has her company broken in upon by the police. Such things make my blood boil, “Confederate blood,” the Era would say. Mrs. Wells was here yesterday; just received a letter from her daughter whom she sent outside the lines months ago. The officers tell her, Mattie Wells says, that everything is going on splendidly for us, and that our troubles will be over in May. Sarah Wells also writes that they all look cheerful, and are far from starvation. Matty Wells has been the victim of a physician’s blunder—he gave her poison, fortunately not in sufficient quantities to cause death, but she was perfectly blind for days. The mother is almost crazed about her two girls. She is here alone, her husband’s property having been seized here. He ran the blockade and went to Vera Cruz. Her relations at the North are very rich. She says she would go to them but fears her girls would not be happy there. They were born in the South, though they have until now passed much time in the North, and loved it. The horrors of this civil strife are too great to realize. I saw a day or two ago two sad-looking women on the street. “This is fulfilling the Scriptures,” said one; “the sons are fighting against the fathers, and the fathers against the sons.”

Mrs. Wilkinson has not yet gone out, having been put off from day to day by these miserable wretches here. Those who have taken the oath and are favorable to the Federal cause, can go out. The officers will positively deny that there is a schooner or any other opportunity for removal, when they know just as positively that people of their own stamp, who will swear to anything, are going often. The Wilkinsons have frequently summoned their friends for last goodbyes, having been promised immediate transit, but here they are still. The Wilkinson girls hurried Mary Ogden and Betty Neely in from Greenville day before yesterday, having been promised by General Sherman that they should go out the next day; the same gentleman told Mrs. Wells the very same day that they would not get off for weeks. They are sitting with their trunks packed and their daily interests are suspended, having been told that they might receive but an hour’s notice to depart. They treat Mrs. Wilkinson this way because her sons are in the army, her husband killed at Manassas, and because she will not take the oath. Mary Ogden was here yesterday, looking very badly and complaining. Lizzie and Jule look like roses; so also does Betty Neely. Mrs. Dameron, too, looks very healthy and very pretty. She is plump and clean-looking. She has been parted from the kindest and best of husbands for a whole year now. What a blessed thing good nerves are; ’tis a good thing, too, to lack that realizing sense of surrounding evils which eats out the very life principle when it once takes possession. It kills Ginnie and myself; we dwell on our misfortunes and those of others until the whole world seems Hope’s sepulcher.

Doctor Cartwright once said to Ginnie, “Oh, what a joyous little creature you were intended to be by Nature—how happy you might have been.” The old Doctor saw that no disease but that of the mind preyed upon her. He tried once to learn of me what it was that made her so unhappy, but finding that I could not confide, he desisted and wound up by telling me that we must go about more and be cheerful. We must marry, he said; but learning that it was quite impossible for us to love anyone, he said that it was not necessary for a woman to love before marriage, so that a man did. “Every woman,” said he, “will love the man who is kind to her.” Heavens, what a theory! The Doctor is a theorist, I know, but I am glad that he has not the power to practice upon his patients after this style. He was horrified when I told him that if I married a person without love that I should hate him afterward and myself, too. Dr. C—— realizes more fully than any man I ever knew the word “philosopher,” but no man knows how to philosophize about a woman—there are pages in her heart-history which the wisest of them can never read.

Many friends have been to see us. Ginnie looks so tired and ill; she is constantly telling me that I look so; indeed, our great anxiety about each other does us much harm. To meet her sad, pale face in the mornings is sometimes as much as I can bear. We two have grown to love each other very tenderly. People laugh and say that they think of us as one person. Our most angry words with one another are in the other’s behalf. Indeed, I am often worried over Ginnie when she refuses to eat some little delicacy, which these hard times have made scarce, because I won’t take it, too. It is very common for us to say to each other, “I will not touch one mouthful unless you do, too.” This seems a silly way to act, and sillier to record, but even in small matters we think the most of the other’s comfort than our own; to save the other little labors more than repays for taking them to ourselves. I know that if I were to die Ginnie could not be comforted, and should I lose her, I am finished forever. Were there no death or suffering in the world such love would be a source of infinite sweetness, but as it is, there is fear in every heart-throb.

The time passes; we hear no word from those that are near and dear. If letters have been sent, they have failed to reach us in these sad times. My sisters, my poor maimed brother, can it be that we are never, never to meet any more? It seems so. We may die in this Yankee-beset town and have no kindred to close our eyes! I sometimes wonder if they are not very anxious about us; but they know that we have friends here, and may not remember us as we remember them. Indeed, I would not wish them to know how we suffer, knowing that they can not reach us with help. Whenever I have been able to send off a few lines to them, I have said that we are well and safe. God forgive the untruth, but I hope some of my words have reached them. We are as well as sleepless nights and headaches from anxiety can leave us, and we have some friends, and many who say they are friends—one whom I would trust as a brother and one to whom I would not fear to open my heart as to a sister. I shall never forget Mr. Randolph and Mrs. Waugh. Simple-hearted, honest, true and kind, wiser and more spirited than those who pretend to more.