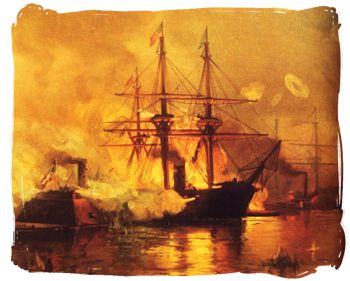

April 28th. Commences with pleasant weather; during this morning the Albatross and Switzerland got under way and entered the mouth of Red River, going up that stream a short distance on a reconnoissance; returned during the afternoon without having seen the enemy, or any batteries erected by him to prove that he was in the vicinity. A rumor is afloat to-day among the ship’s company that Charleston has lately been attacked by our army and naval forces and captured. We have nothing definite, though, in regard to the truth of such report; still it has its believers, and they are much excited over it. I have no doubt but that ere long we will have something happen that will cause more excitement and rejoicing than the fall of Charleston; I mean the surrender of Vicksburg and Port Hudson. The weather is cool and pleasant, the rain of yesterday having purified the atmosphere to a great extent.

Sunday, April 28, 2013

28th. Up at daylight, breakfasted, fed and started on at 6. Gen. Carter passed by. Went but two miles and waited an hour or two. River not fordable. Returned and bivouacked on the ground of the night before. Went out foraging corn, hay, and cornbread and milk. Saw two idiots. Rained again. Got somewhat wet. Two of the 2nd O. V. C. companies on picket.

Tuesday, 28th—James Hawkins came up to-day to see me; staid all day with me. After he left, I and Frank McGuire went out to Mr. Bradley’s and got supper. I got some bread. We then went and got twenty bundles fodder apiece and came back to Camp.

28th April (Tuesday).—We crossed the river Guadalupe at 5 A.M., and got a change of horses.

We got a very fair breakfast at Seguin at 7 A.M., which was beginning to be a well-to-do little place when the war dried it up.

It commenced to rain at Seguin, which made the road very woolly, and annoyed the outsiders a good deal.

The conversation turned a good deal upon military subjects, and all agreed that the system of election of officers had proved to be a great mistake. According to their own accounts, discipline must have been extremely lax at first, but was now improving. They were most anxious to hear what was thought of their cause in Europe; and none of them seemed aware of the great sympathy which their gallantry and determination had gained for them in England in spite of slavery.

We dined at a little wooden hamlet called Belmont, and changed horses again there.

The country through which we had been travelling was a good deal cultivated, and there were numerous farms. I saw cotton-fields for the first time.

We amused ourselves by taking shots with our revolvers at the enormous jack-rabbits which came to stare at the coach.

In the afternoon tobacco-chewing became universal, and the spitting was sometimes a little wild.

It was the custom for the outsiders to sit round the top of the carriage, with their legs dangling over (like mutes on a hearse returning from a funeral). This practice rendered it dangerous to put one’s head out of the window, for fear of a back kick from the heels, or of a shower of tobacco-juice from the mouths, of the Southern chivalry on the roof. In spite of their peculiar habits of hanging, shooting, &c, which seemed to be natural to people living in a wild and thinly-populated country, there was much to like in my fellow-travellers. They all had a sort of bonhommie honesty and straightforwardness, a natural courtesy and extreme good-nature, which was very agreeable. Although they were all very anxious to talk to a European—who, in these blockaded times, is a rara avis—yet their inquisitiveness was never offensive or disagreeable.

Any doubts as to my personal safety, which may have been roused by my early insight into Lynch law, were soon completely set at rest; for I soon perceived that if any one were to annoy me the remainder would stand by me as a point of honour.

We supped at a little town called Gonzales at 6.30.

We left it at 8 P.m. in another coach with six horses —big strong animals.

The roads being all natural ones, were much injured by the rains.

We were all rather disgusted by the bad news we heard at Gonzales of the continued advance of Banks, and of the probable fall of Alexandria.

The squeezing was really quite awful, but I did not suffer so much as the fat or long-legged ones. They all bore their trials in the most jovial good-humoured manner.

My fat vis-d-vis (in despair) changed places with me, my two bench-fellows being rather thinner than his, and I benefited much by the change into a back seat.

Tuesday, 28th—It cleared off this morning and we left Richmond at 10 o’clock, marched nine miles and went into camp on Holmes’s plantation, about eight miles from the Mississippi and due west from Vicksburg. We took possession of all the vacant houses and sheds on the plantation. The roads are very muddy and many of the trains got stalled. Some of the wagons loaded with ammunition sank down to the axles and much time and labor were consumed in getting them out. There was some fighting at Grand Gulf today.

Tuesday, 28th.—Started on picket last night at 5 o’clock; went to five-mile bridge. Reported Yankees are trying to cross river near Warrenton. Some skirmishing.

April 28 — We renewed our march early this morning and kept on a steady move all day, over a good grade, although some of the country we passed through is rough and hilly and the Valley is full of fragmentary mountain-like hills scattered around promiscuously. We forded the South Branch but once to-day, at Kile’s Ford, which was very deep and rough. At some places the grade winds along at the foot of steep and rocky bluffs, and at other places through rich and beautiful alluvial bottoms along the river; then again through dense mountain forests of oak and pine, with a thick undergrowth of laurel and mountain shrubbery. We marched twenty-three miles to-day, and are camped this evening one mile below Franklin.

April 28.—One of my patients, by the name of Lee, has just died; was a member of the Thirty-third Alabama Regiment. His wife lives in Butler County, Alabama. He was out of his mind previous to his death.

A number of wounded Federals were brought in a few days ago.

April 28, Tuesday. Nothing at Cabinet, Seward and Chase absent. The President engaged in selecting provost-marshals.

Sumner called this evening at the Department. Was much discomfited with an interview which he had last evening with the President. The latter was just filing a paper as Sumner went in. After a few moments Sumner took two slips from his pocket, — one cut from the Boston Transcript, the other from the Chicago Tribune, each taking strong ground against surrendering the Peterhoff mail. The President, after reading them, opened the paper he had just filed and read to Sumner his letter addressed to the Secretary of State and the Secretary of the Navy. He told Sumner he had received the replies and just concluded reading mine. After some comments on them he said to Sumner, “I will not show these papers to you now; perhaps I never shall.” A conversation then took place which greatly mortified and chagrined Sumner, who declares the President is very ignorant or very deceptive. The President, he says, is horrified, or appeared to be, with the idea of a war with England, which he assumed depended on this question. He was confident we should have war with England if we presumed to open their mail bags, or break their seals or locks. They would not submit to it, and we were in no condition to plunge into a foreign war on a subject of so little importance in comparison with the terrible consequences which must follow our act. Of this idea of a war with England, Sumner could not dispossess him by argument, or by showing its absurdity. Whether it was real or affected ignorance, Sumner was not satisfied.

I have no doubts of the President’s sincerity, and so told Sumner. But he has been imposed upon, humbugged, by a man in whom he confides. His confidence has been abused; he does not — frankly confesses he does not — comprehend the principles involved nor the question itself. Seward does not intend he shall comprehend it. While attempting to look into it, the Secretary of State is daily, and almost hourly, wailing in his ears the calamities of a war with England which he is striving to prevent. The President is thus led away from the real question, and will probably decide it, not on its merits, but on this false issue, raised by the man who is the author of the difficulty.

Camp near FALMOUTH, April 28, 1863.

DEAR FATHER, — I think we shall start to-morrow night, if it does not rain. The pontoons are all near the river, and everything is in readiness to move. Some of the corps have moved up near the river to-day, in order to move promptly and quickly when the order comes. It seems to me that we shall cross in three places: at Bank’s Ford, where Franklin crossed at Fredericksburg fight, and about a mile below Franklin’s position.

In regard to the feeling in the army, it is not so good as it was. There is a feeling that the golden opportunity has passed away, and that if we cross now we shall have Hill and Longstreet’s forces to contend with in addition to Lee’s force. Had we gone over last Monday, we should not have half the force to contend against that we have now. However, it does not do to give way to any such feelings, especially before the men, and we must all do the utmost in our power to help and aid General Hooker. In regard to his drinking, I will say to you what I have never spoken about to any one else outside the army. I know of his having been tight twice since I have been here, although I hope he does not indulge enough to render him incompetent to perform his duty. He is, to tell the truth, a brave, dashing soldier, rather an adventurer than anything else, and bound to win or lose everything. Too much given to boasting and talking, he is nevertheless a man who will win the love and admiration of the soldiers, provided that he succeeds in his first fight. Whether he possesses the ability and the power to handle this large army remains to be seen. So far, in my opinion, General Butterfield has “run the machine,” and he is admirably fitted to attend to its internal discipline, etc. I feel anxious myself in regard to General Hooker, on account of the numerous delays we have had. They are certainly as bad, if not worse, than any of McClellan’s, and we must certainly admit that either Hooker is right and McClellan also, or that Hooker is wrong as much as McClellan ever was. Every one here begins to say now, “Well, McClellan was right after all.” I do hope most earnestly that by the time you receive this letter you will also have the news of our crossing the river successfully, and giving the enemy a good whipping.

To-night it seems to threaten a storm for to-morrow. We get ready to move during the pleasant weather and are on the point of starting just as the rain begins again.

I was called up this morning to write some private dispatches for an officer going on a secret expedition. General and myself were the only ones around here who knew of the place and object of the officer’s journey. The officer himself did not know, as the dispatches were sealed and were not to be opened until he reached Washington. Yet this afternoon I was told by an officer where and for what purpose the officer was sent. It leaked out from headquarters of the Army of the Potomac in some way. It is a difficult thing to keep anything secret.