Tuesday, 26.—3 A. M. Ordered to Warrenton Road near river; put in ditches; several prisoners taken by a sortee party.

Sunday, May 26, 2013

Headquarters 1st Army Corps, May 26, 1863.

Dear Father, — I am happy to say that I have left General Benham and gone with General Reynolds. My position here is only as acting aide, but still it is on a corps staff, and with a brave and fine general. I might have obtained a position on Crawford’s staff or on General Barnes’s staff as a regular aide, but I preferred this place. I told General Benham that I should like to leave him, and soon after I met General Reynolds, to whom I told the whole story. He told me that I acted perfectly right throughout the whole affair. . . .

I see no prospect of our moving for some three or four months. Our army is growing smaller every day and will soon be reduced to 55,000 men fit for duty. Our loss in the recent battles was between 17,000 and 18,000 men in killed, wounded, and missing. This is true, although the officer in command of this army has reported it at only to 10,000 or 12,000. He has also reported that one cause of his retreat was the rising of the river, on account of the storm. Now, I know that the retreat was ordered long before the storm came up, some 12 hours before. I was at United States Ford when the storm began, and our wagons and part of our artillery had started some time before. I think it possible that General Hooker may have been seriously affected by that shell which struck a pillar he was leaning against and knocked him senseless. I think that he may not have recovered from the shock for some days and that he was not himself when he ordered the retreat. His plan certainly seems to have been a good one.

I wish you would send me the Saturday Evening Gazette once in a while. It has some articles in it that are quite interesting. . . .

General Reynolds has treated me very kindly through out this whole affair. I spoke to General Sedgwick after I had this place on General R.’s staff, and told him what I had done. He also said that I had acted perfectly right in the whole affair. When he saw me coming into his tent, he said, “Well, Weld, has old Benham shipped you or have you shipped old Benham?” He was very kind to me. General Benham has been boring him dreadfully about this matter and he is thoroughly sick of him.

General Benham’s adjutant-general, inspector-general, and his other aide have left him, and the remaining two officers on his staff will leave as soon as possible.

May 26.— Remained in camp all day. The expedition from the Neck returned this noon. Captain Clapp, Captain Strang, and Lieutenant Perkins were here this evening. The weather was moderately cool to-day. Captains Batchelder and Jay were here to lunch.

Tuesday, 26th—It was quiet all along the line last night. The rebels came out with a flag of truce, asking permission to bury their dead, killed during the day. Our brigade started towards the right this morning, and arriving at McPherson’s headquarters at the center, we went into bivouac for the night. Our march was over hot and dusty roads. Our guns commenced to shell the rebels again this afternoon.

May 26th.—Up this morning at three o’clock, with orders for three days’ rations in our haversacks and five days’ in the wagons —also to be ready to move at ten o’clock to the rear, in pursuit of Johnston, who was thrusting his bayonets too close to our boys there.

I am not anxious to get away from the front, yet a little marching in the country will be quite a desirable change, and no doubt beneficial to our men. I have been afraid we might be molested in the rear, for we were having our own way too smoothly to last. I think the confederate authorities are making a great mistake in not massing a powerful army in our rear and thus attempting to break our lines and raise the siege. We shall attend to Johnston, for Grant has planted his line so firmly that he can spare half his men to look out for his rear. What a change we notice to-day, from the time spent around the city, where there was no sound except from the zipping bullets and booming cannon; while out here in the country the birds sing as sweetly as if they had not heard of war at all. Here, too, we get an exchange from the smoky atmosphere around Vicksburg, to heaven’s purest breezes.

We have marched to-day over the same ground for which we fought to gain our position near the city. Under these large spreading oaks rest the noble dead who fell so lately for their country. This march has been a surprise to me. It is midnight, and we are still marching.

Letter No. III.

Camp on the Rapidan,

May 26th, 1863.

My Precious Wife:

The order to move has been countermanded for the present, and we will be on picket duty for a few days. I wrote you yesterday, thinking it was Tuesday, and that Mr. Robinson would leave today; so I will continue the account of my trip from Columbia. I left there on the 20th in company with Decca Stark, who was about to pay a visit to Mrs. Jennie Preston Means. I found Stark Means at the depot in Winsboro. He is looking very well and his wounds have nearly healed. I found all those up-country villages a great deal larger and more prosperous looking than I expected.

When I reached Weldon I found Troutman there as quartermaster, and spent an hour or two with him very pleasantly, talking over old college days. He has married Miss Napier and seems to be in good circumstances. Miss Lou Neely has married Ed. McClure. John Neely is dead. John McLemore, Lucius Gaston and Charlie Boyd (Capt), have all been killed in battle. The sacrifice of a nation of hired Hessians will not atone for the loss of such men as these. I took supper with Troutman, at the commissary’s residence, and had a first-rate meal. I reached Richmond on Friday morning about 9 o’clock, and after paying a barber $2.50 for a shave and shampoo I took a stroll over the city; called on Mrs. Wigfall, Mrs. Chestnut, Miss Barn well, etc., etc., and found all at home except Miss Nannie Norton, whom I also called to see; and I also called on Miss Mary E. Fisher. Miss Nannie was on a visit to Raleigh.

I had a letter from Mrs. Julia Bachman to Miss Fisher. She asked me in and gave me a drink of water, flavored with mint, which was very acceptable. Mrs. Carter, whom I met at Mrs. Barnwell’s, seemed very glad to hear from you and asked to be remembered to you. Mr. Barnwell was quite sick. Mrs. Chestnut invited me to dine and Willie Preston to meet me; he is a major of artillery. Jack Preston has married Miss Huger. I delivered Mr. Carter’s letter to Mr. Winston, but he had no time to talk to me; he has a task for each day and not a moment to spare. I spent more of my time sightseeing, but was especially interested in the equestrian statue of Washington, which surmounts a plain shaft of marble, with a granite base. There are also on the same monument statues of Jefferson, Mason and Henry. This is in Capitol Square, which is beautifully shaded. The Square is a great resort for all classes in leisure hours. Just at this point I was called out to our company drill, which has given me an hour and a half of good exercise. I must write a letter to some of the folks at Austin; so will have to curtail this. Let me repeat, you must take good care of yourself and not trouble about me. If you cannot manage any other way you must quit thinking of me entirely, except enough to keep from forgetting me altogether. My little picture of you copied from one in Columbia is charming, and is a source of great pleasure to me. Tell the servants to behave well, and to obey you, or I will haunt them. Talk to the children about me every day and tell Stark to say his lessons regularly.

Your husband, faithfully ever,

John C. West.

May 26, Tuesday. Much of the time at the Cabinet meeting was consumed in endeavoring to make it appear that one Cuniston, tried and condemned as a spy, was not exactly a spy, and that he might be let off. I did not participate in the discussion. It appeared to me, from the statement on all hands and from the finding of the court, that he was clearly and beyond question a spy, and I should have said so, had my opinion been asked, but I did not care to volunteer, unsolicited and without a thorough knowledge of all the facts, to argue away the life of a fellow being.

There was a sharp controversy between Chase and Blair on the subject of the Fugitive Slave Law, as attempted to be executed on one Hall here in the district. Both were earnest, Blair for executing the law, Chase for permitting the man to enter the service of the United States instead of being remanded into slavery. The President said this was one of those questions that always embarrassed him. It reminded him of a man in Illinois who was in debt and terribly annoyed by a pressing creditor, until finally the debtor assumed to be crazy whenever the creditor broached the subject. “I,” said the President, “have on more than one occasion, in this room, when beset by extremists on this question, been compelled to appear to be very mad. I think,” he continued, ” none of you will ever dispose of this subject without getting mad.”

I am by no means certain that it is wise or best to commence immediate operations upon Charleston. It is a much more difficult task now than it was before the late undertaking. Our own men have less confidence, while our opponents have much more. The place has no strategic importance, yet there is not another place our anxious countrymen would so rejoice to see taken as this original seat of the great wickedness that has befallen our country. The moral effect of its capture would be great.

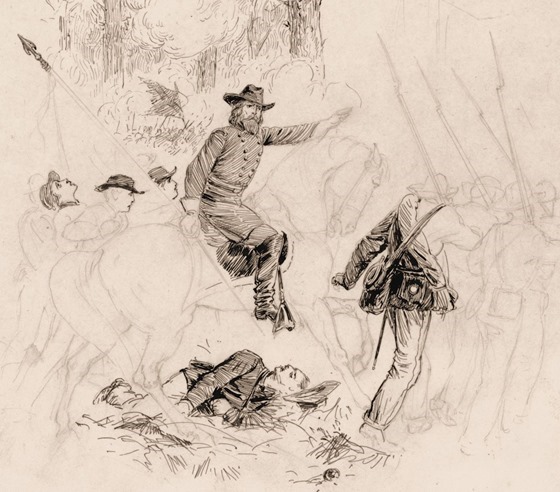

Drawing by Alfred R. Waud, date and location not identified; Library of Congress image.

26th. Charlie came over in the morning. Finished letters home and to Fannie A. Yesterday was birthday of Fred Allen. Wrote him a congratulatory letter according to program. Rode over to town with the letters. Letter from home—Minnie.

26th May (Tuesday).—When I took Colonel Ewell’s pass to the provost-marshal’s office this morning to be countersigned, that official hesitated about stamping it, but luckily a man in his office came to my rescue, and volunteered to say that, although he didn’t know me himself, he had heard me spoken of by others as “a very respectable gentleman.” I was only just in time to catch the twelve o’clock steamer for the Montgomery railroad. I overheard two negroes on board discussing affairs in general; they were deploring the war, and expressing their hatred of the Yankees for bringing “sufferment on us as well as our masters.” Both of them had evidently a great aversion to being “run off,” as they called it. One of them wore his master’s sword, of which he was very proud, and he strutted about in a most amusing and consequential manner.

I got into the railroad cars at 2.30 P.M.; the pace was not at all bad, had we not stopped so often and for such a long time for wood and water. I sat opposite to a wounded soldier who told me he was an Englishman from Chelsea. He said he was returning to his regiment, although his wound in the neck often gave him great pain. The spirit with which wounded men return to the front, even although their wounds are imperfectly healed, is worthy of all praise, and shows the indomitable determination of the Southern people. In the same car there were several quite young boys of fifteen or sixteen who were badly wounded, and one or two were minus arms and legs, of which deficiencies they were evidently very vain.

The country through which we passed was a dense pine forest, sandy soil, and quite desolate, very uninviting to an invading army. We travelled all night.