Thursday, 4th—Wm. Hamby got in from Austin, Texas; staid all night with me. We went out to a private house and spent the night.

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

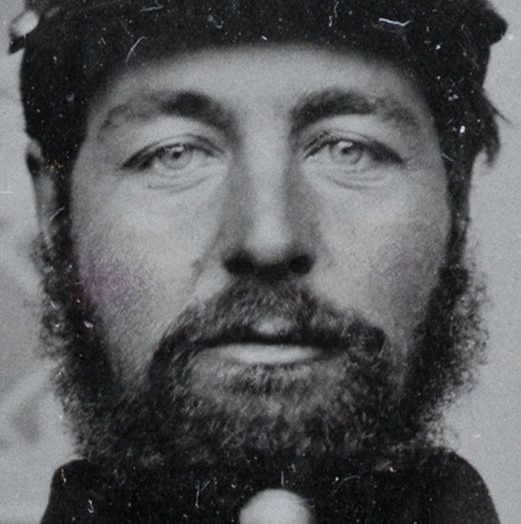

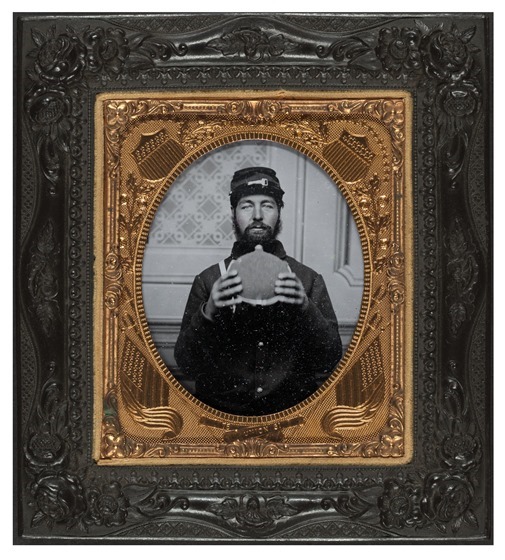

Unidentified soldier in Union uniform with canteen

Unidentified soldier in Union uniform with canteen

__________

__________

Sixth-plate ambrotype, hand-colored ; 12.3 x 11.1 cm (frame) Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot and/or scratch removal

- cropped for composition and/or to accentuate subject matter

- straighten image

Civil War Portrait 099

Headquarters 1st Army Corps, June 4, 1863.

Dear Father, — Will you please make an application for my degree as A.M. I think that I receive it this year; if possible I shall try and get a leave of absence to come home for Commencement, but I am afraid that I shall stand a slim chance of getting it. . . .

I received a letter from Hannah yesterday, saying that I had received a commission as captain in my regiment. Will you please send me a copy of the paper announcing it. My regiment is at United States Ford at present, so that I have no chance to see my colonel about it at present.

I spoke to Palfrey this morning in regard to what you wrote about getting him a commission in the 55th. He was very much obliged to you, and said that Dr. Palfrey and Charles Hale were both trying to get him a commission, that he would not like to lose any chance for a commission that they might have obtained for him, by asking for one in the 55th. I think the best plan would be for you to see them, and if they have any chance of getting him a place in a white regiment, then you could aid them. If not, why then he would like a position in the 55th, and you three could probably obtain it for him. I would be very much obliged to you if you could get him a place. I enclose a note from him to you.

We are under orders to march at any moment, probably to resist any attempt the enemy may make to cross the river. The rascals are up to something, and I think it may be that they will try to cross the river above, and attack us. I think that we are waiting here simply to prevent the rebels opposite from going to Vicksburg. Were it not for the critical state of affairs there, I think we should go to Washington, in order to fill up the army with conscripts, and reorganize it. . . .

June 4. — I got up about 2 o’clock, and had all our things packed up, expecting to start, but nary move did we have. Remained in camp all day. Wrote Father in regard to Palfrey[1], and forwarded his application for a commission. Heard this evening that Colonel Dana, our quartermaster, had resigned.

[1] Hersey G. Palfrey, of the class of 1860.

JUNE 4TH.—We move at last. We left camp as the sun rose, reaching our old quarters in front of the rebel Fort Hill in the afternoon. Glad we are to get here. A great change has taken place during our ten days’ absence. More rifle-pits have been made and new batteries erected, and our lines generally have been pushed closer to the works of the enemy. Mines are being dug, and we shall soon see something flying in the air in front of us, when those mines explode. The work is being done very secretly, for it would not do to have the rebels find out our plans. Fort Hill in our front and on the Jackson road is said to be the key to Vicksburg. We have tried often to turn this key, but have as often failed. In fact, the lock is not an easy one. The underground work now going on will perhaps break the lock with an explosion. Our return to camp from our excursion after Johnston creates some excitement among those who stayed behind. They all want to hear about our trip, and what we saw and conquered. Our clothes are so dirty and ragged, that though we have sewed and patched, and patched and sewed, Uncle Sam would hardly recognize those nice blue suits he gave us a little while ago. This southern sun pours down a powerful heat, which compels us to keep as quiet as possible. Just a month from today we celebrate our Fourth of July—where, I do not know, but inside of Vicksburg, I hope.

I have asked both officers and men to write in an album I have opened since reaching our old post near the city, and here are a few of their contributions :

__________

“Friend O.: Here is hoping we may see the stars and stripes float over the court house in Vicksburg on the Fourth of July, and also that we may see this rebellion, in which so many of our comrades have fallen, come to an end, while we live on to enjoy a peace secured by our arms. Then hurrah for the Buckeye girls. Your sincere friend,

HENRY H. FULTON,

“Company E, 20th Ohio.”__________

“Here is hoping we may have the pleasure of zweiglass of lager in Vicksburg, on July 4th.

“D. M. COOPER,

“Company A, 96th Ohio.”__________

“I hope we shall be able to spend the coming Fourth in the famous city before us, and to have a glorification there over our victories.

“SQUIRE MCKEE,

“Company E, 20th Ohio.”__________

“Here is hoping that by the glorious Fourth, and by the force of our arms, we shall penetrate their boasted Gibraltar.

“T. B. LEGGETT,

“Company E, 20th Ohio.”__________

“I offer you this toast: Though you have seen many hardships, let me congratulate you on arriving safely so near Vicksburg. May the besieged city fall in time for you and all our boys to take a glass of lager on the Fourth of July; and may the boys of the Twentieth be the first to taste the article they have duly won.

“D. B. LINSTEAD,

“Company G, 20th Ohio.”

Thursday, 4th—We left early this morning to join the army in the rear of Vicksburg, and arrived at General McPherson’s headquarters about 5 o’clock in the evening. Here we stacked arms and formed a line of battle. Our men are still shelling Vicksburg day and night. We are here on high ground, but cannot see the town of Vicksburg.

Colonel Lyons.

Fort Donelson, June 4, 1863.—Soon after I went over to headquarters this morning, an order came to me from General Rosecrans to send the 5th Iowa Cavalry to Murfreesboro, and then another directing me to gather up horses and mount enough infantry for patrols, pickets and scouts. The cavalry will cross the river tomorrow and march by Clarksville and Nashville. The 1st Wisconsin Cavalry, now at Eddyville, will join them at Clarksville. This order settles matters here by throwing the command of this post on my shoulders, and probably fastens us here for some time. I do not know, but presume, that Colonel Lowe will have a cavalry brigade at the front. We don’t hear a word from him. You know I feared this result when Colonel Lowe was ordered to headquarters. The responsibility of this command is heavy and I would gladly avoid it. It would be a very honorable command for a Brigadier-General, and is a larger and more responsible one than many of them have. Unless there is some change I have a laborious and anxious summer before me, but I will try to get along with it. I shall start an expedition in a day or two for horses.

June 4 — We renewed our march this morning and moved to Culpeper Court House. Just before we got to town we passed the camp of a battalion of the German Artillery, from South Carolina. It belongs to General Hood’s division, and is considered one of the best battalions of artillery in the Confederate Army.

Culpeper Court House is a pretty town pleasantly situated on the gently rising slope of a hill in a rather rolling and diversified section of country. West of the town toward the Blue Ridge the country is broken by wooded ridges, but looking east and south toward the lower Rapidan the country is beautiful and open, the land being nearly level and of good quality. The town is situated on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad about nine miles from the Rappahannock River. It contains about one thousand inhabitants. Main Street is wide and straight and in general appearance it resembles an embryo city street. We are camped this evening half mile east of Culpeper Court House.

June 4, Thursday. Only a sense of duty would have led me to relieve Du Pont and Wilkes. With D. my relations have been kind and pleasant, on my part confiding. Latterly he has disappointed me, and given indication that my confidence was not returned. Wilkes is a different man and of an entirely different temperament. Du Pont is pleasant in manner and one of the most popular officers in the Navy; Wilkes is arbitrary and one of the most unpopular. There are exceptions in both cases. Du Pont is scrupulous to obey orders; Wilkes often disregards and recklessly breaks them. The Governments of Great Britain, Denmark, Mexico, and Spain have each complained of Wilkes, but, except in the case of Denmark, it appears to me without much cause, and even in the case of Denmark the cause was aggravated. There was some mismanagement in the Mexican case that might not stand close scrutiny. As regards the rights of neutrals, he has so far as I yet know, deported himself correctly, and better than I feared so far as England is concerned, after the affair of the Trent and with his intense animosity towards that government. His position has doubtless been cause of jealousy and irritation on the part of Great Britain, and in that respect his selection from the beginning had its troubles. He has accomplished less than I expected; has been constantly grumbling and complaining, which was expected; has captured a few blockade-runners, but not an armed cruiser, which was his special duty, and has probably defeated the well-devised plan of the Navy Department to take the Alabama. At the last advices most of his squadron was concentrated at St. Thomas, including the Vanderbilt, which should then have been on the equator, by specific orders. To-day Mrs. Wilkes, with whom we have been sociable, and I might almost say intimate, writes Mrs. Welles a note asking if any change has been made in the command of the West India Squadron. This note was on my table as I came out from breakfast. The answer of Mrs. Welles was, I suppose, not sufficiently definite, for I received a note with similar inquiries in the midst of pressing duties, and the messenger was directed to await an answer. I frankly informed her of the change. Alienation and probably anger will follow, but I could not do differently, though this necessary official act will, not unlikely, be resented as a personal wrong.

4th June (Thursday).—Colonel Richmond rode with me to the outposts, in order to be present at the reconnaissance which was being conducted under the command of General Cheetham. We reached the field of operations at 2 P.m., and found that Martin’s cavalry (dismounted) had advanced upon the enemy about three miles, and, after some brisk skirmishing, had driven in his outposts. The enemy showed about 2000 infantry, strongly posted, his guns commanding the turnpike road. The Confederate infantry was concealed in the woods, about a mile in rear of the dismounted cavalry.

This being the position of affairs, Colonel Richmond and I rode along the road so far as it was safe to do so. We then dismounted, and sneaked on in the wood alongside the road until we got to within 800 yards of the Yankees, whom we then reconnoitred leisurely with our glasses. We could only count about seventy infantry soldiers, with one field-piece in the wood at an angle of the road, and we saw several staff officers galloping about with orders. Whilst we were thus engaged, some heavy firing and loud cheering suddenly commenced in the woods on our left; so, fearing to be outflanked, we remounted and rode back to an open space, about 600 yards to the rear, where we found General Martin giving orders for the withdrawal of the cavalry horses in the front, and the retreat of the skirmishers.

It was very curious to-see three hundred horses suddenly emerge from the wood just in front of us, where they had been hidden—one man to every four horses, riding one and leading the other three, which were tied together by the heads. In this order I saw them cross a cotton-field at a smart trot, and take up a more secure position; two or three men cantered about in the rear, flanking up the led horses. They were shortly afterwards followed by the men of the regiment, retreating in skirmishing order under Colonel Webb, and they lined a fence parallel to us. The same thing went on on our right.

As the firing on our left still continued, my friends were in great hopes that the Yankees might be inveigled on to follow the retreating skirmishers until they fell in with the two infantry brigades, which were lying in ambush for them; and it was arranged, in that case, that some mounted Confederates should then get in their rear, and so capture a good number; but this simple and ingenious device was frustrated by the sulkiness of the enemy, who now stubbornly refused to advance any further.

The way in which the horses were managed was very pretty, and seemed to answer admirably for this sort of skirmishing. They were never far from the men, who could mount and be off to another part of the field with rapidity, or retire to take up another position, or act as cavalry as the case might require. Both the superior officers and the men behaved with the most complete coolness; and, whilst we were waiting in hopes of a Yankee advance, I heard the soldiers remarking that they “didn’t like being done out of their good boots”—one of the principal objects in killing a Yankee being apparently to get hold of his valuable boots.

A tremendous row went on in the woods during this bushwhacking, and the trees got knocked about in all directions by shell; but I imagine that the actual slaughter in these skirmishes is very small, unless they get fairly at one another in the open cultivated spaces between the woods. I did not see or hear of anybody being killed to-day, although there were a few wounded and some horses killed. Colonel Richmond and Colonel Webb were much disappointed that the inactivity of the enemy prevented my seeing the skirmish assume larger proportions, and General Cheetham said to me, “We should be very happy to see you, Colonel, when we are in our regular way of doing business.”

After waiting in vain until 5 P.m., and seeing no signs of anything more taking place, Colonel Richmond and I cantered back to Shelbyville. We were accompanied by a detachment of General Polk’s body-guard, which was composed of young men of good position in New Orleans. Most of them spoke in the French language, and nearly all had slaves in the field with them, although they ranked only as private soldiers, and had to perform the onerous duties of orderlies (or couriers, as they are called). On our way back we heard heavy firing on our left, from the direction in which General Withers was conducting his share of the reconnaissance with two other infantry brigades.

After dark General Polk got a message from Cheetham, to say that the enemy had after all advanced in heavy force about 6.15 P.M., and obliged him to retire to Guy’s Gap. We also heard that General Cleburne, who had advanced from Wartrace, had had his horse shot under him. The object of the reconnaissance seemed, therefore, to have been attained, for apparently the enemy was still in strong force at Murfreesborough, and manifested no intention of yielding it without a struggle.

I took leave of General Polk before I turned in. His kindness and hospitality have exceeded anything I could have expected. I shall always feel grateful to him on this account, and I shall never think of him without admiration for his character as a sincere patriot, a gallant soldier, and a perfect gentleman. His aides-de-camp, Colonels Richmond and Yeatman, are also excellent types of the higher class of Southerner. Highly educated, wealthy, and prosperous before the war, they have abandoned all for their country. They, and all other Southern gentlemen of the same rank, are proud of their descent from Englishmen. They glory in speaking English as we do, and that their manners and feelings resemble those of the upper classes in the old country. No staff-officers could perform their duties with more zeal and efficiency than these gentlemen, although they were not educated as soldiers.