Thursday, 23d—We were off by 4 o’clock this morning and reached Big Black river bridge by noon. It had rained very hard here yesterday and last night, overflowing the river and causing the deep dust to become deep mud. This made our traveling very heavy, and since the rain set in again this afternoon, we moved on only about three miles and went into bivouac.

Tuesday, July 23, 2013

July 23, Thursday. I had a call on Monday morning from Senator Morgan and Sam J. Tilden of New York in relation to the draft. General Cochrane was present during the interview and took part in it. The gentlemen seemed to believe a draft cannot be enforced in New York.

Am feeling anxious respecting movements in Charleston Harbor. It is assumed on all hands by the people and the press that we shall be successful. I am less sanguine, though not without hopes. Fort Wagner should have been captured in the first assault. The Rebels were weaker then than they will be again, and we should have been as strong at the first attack as we can expect to be. Gillmore may have been a little premature, and had not the necessary force for the work.

Whiting, Solicitor of the War Department, has gone to Europe. Is sent out by Seward, I suppose, for there is much sounding of gongs over the mission instituted by the State Department to help Mr. Adams and our consuls in the matter of fitting, or of preventing the fitting out of naval vessels from England. This Solicitor Whiting has for several months been an important personage here. I have been assured from high authority he is a remarkable man. The Secretary of War uses him, and I am inclined to believe he uses the Secretary of War. This fraternity has made the little man much conceited. Mr. Seward, Mr. Chase, and even the President have each of them spoken to me of him, as capable, patriotic, and a volunteer in the civil service to help the Government and particularly the War Department.

I have found him affable, anxious to be useful, with some smartness; vain, egotistical, and friendly; voluble, ready, sharp, not always profound, nor wise, nor correct; cunning, assuming, presuming, and not very fastidious; such a man as Stanton would select and Seward use. Chase, finding him high in the good graces of the President and the Secretary of War, has taken frequent occasion to speak highly of Solicitor Whiting. My admiration is not as exalted as it should be, if he is all that those who ought to know represent him.

July 23.—The enrolment was resisted in the vicinity of Jarrettsville, Harford County, Md.— The First regiment of colored United States volunteers was completed at Philadelphia, Pa., and Colonel Benjamin Tilghman appointed to the command.—The draft took place in Auburn, N. Y., and every thing passed off with the best of order. The occasion, instead of being one of rioting, arson, and murder, was rather one of rejoicing and demonstrations of loyalty. The drafted men formed in procession, with a band of music, and marched through the streets cheering for the draft, the Union, etc., and in the evening listened to patriotic speeches from the Provost-Marshal, the Mayor and others.

July 23 — This afternoon we moved toward White Post. We heard cannonading this evening at Chester’s Gap near Front Royal.

Thursday, July 23d.

It is bad policy to keep us from seeing the prisoners; it just sets us wild about them. Put a creature you don’t care for in the least, in a situation that commands sympathy, and nine out of ten girls will fall desperately in love. Here are brave, self-sacrificing, noble men who have fought heroically for us, and have been forced to surrender by unpropitious fate, confined in a city peopled by their friends and kindred, and as totally isolated from them as though they inhabited the Dry Tortugas! Ladies are naturally hero-worshipers. We are dying to show these unfortunates that we are as proud of their bravery as though it had led to victory instead of defeat. Banks wills that they remain in privacy. Consequently our vivid imaginations are constantly occupied in depicting their sufferings, privations, heroism, and manifold virtues, until they have almost become as demigods to us. Even horrid little Captain C—— has a share of my sympathy in his misfortune! Fancy what must be my feelings where those I consider as gentlemen are concerned! It is all I can do to avoid a most tender compassion for a very few select ones. Miriam and I are looked on with envy by other young ladies because some twenty or thirty of our acquaintance have already arrived. To know a Port Hudson defender is considered as the greatest distinction one need desire. If they would only let us see the prisoners once to sympathize with, and offer to assist them, we would never care to call on them again until they are liberated. But this is aggravating. Of what benefit is it to send them lunch after lunch, when they seldom receive it? Colonel Steadman and six others, I am sure, did not receive theirs on Sunday. We sent with the baskets a number of cravats and some handkerchiefs I had embroidered for the Colonel.

Brother should forbid those gentlemen writing, too. Already a dozen notes have been received from them, and what can we do? We can’t tell them not to. Miriam received a letter from Major Spratley this morning, raving about the kindness of the ladies of New Orleans, full of hope of future successes, and vows to help deliver the noble ladies from the hands of their oppressors, etc. It is a wonder that such a patriotic effusion could be smuggled out. He kindly assures us that not only those of our acquaintance there, but all their brother officers, would be more than happy to see us in their prison. Position of affairs rather reversed since we last met!

I wanted to get the whole of the army of Vicksburg drunk at my own expense. I wanted to fight some small man and lick him.

Henry Adams to Charles Francis Adams, Jr.

[London,] July 23, 1863

I positively tremble to think of receiving any more news from America since the batch that we received last Sunday. Why can’t we sink the steamers till some more good news comes? It is like an easterly storm after a glorious June day, this returning to the gloomy chronicle of varying successes and disasters, after exulting in the grand excitement of such triumphs as you sent us on the 4th. For once there was no drawback, unless I except anxiety about you. I wanted to hug the army of the Potomac. I wanted to get the whole of the army of Vicksburg drunk at my own expense. I wanted to fight some small man and lick him. Had I had a single friend in London capable of rising to the dignity of the occasion, I don’t know what might n’t have happened. But mediocrity prevailed and I passed the day in base repose.

It was on Sunday morning as I came down to breakfast that I saw a telegram from the Department announcing the fall of Vicksburg. Now, to appreciate the value of this, you must know that the one thing upon which the London press and the English people have been so positive as not to tolerate contradiction, was the impossibility of capturing Vicksburg. Nothing could induce them to believe that Grant’s army was not in extreme danger of having itself to capitulate. The Times of Saturday, down to the last moment, declared that the siege of Vicksburg grew more and more hopeless every day. Even now, it refuses, after receiving all the details, to admit the fact, and only says that Northern advices report it, but it is not yet confirmed. Nothing could exceed the energy with which everybody in England has reprobated the wicked waste of life that must be caused by the siege of this place during the sickly season, and ridiculed the idea of its capture. And now the announcement was just as though a bucket of iced-water were thrown into their faces. They could n’t and wouldn’t believe it. All their settled opinions were overthrown, and they were left dangling in the air. You never heard such a cackling as was kept up here on Sunday and Monday, and you can’t imagine how spiteful and vicious they all were. Sunday evening I was asked round to Monckton Milnes’ to meet a few people. Milnes’ himself is one of the warmest Americans in the world, and received me with a hug before the astonished company, crowing like a fighting cock. But the rest of the company were very cold. W. H. Russell was there, and I had a good deal of talk with him. He at least did not attempt to disguise the gravity of the occasion, nor to turn Lee’s defeat into a victory. I went with Mr. Milnes to the Cosmopolitan Club afterwards, where the people all looked at me as though I were objectionable. Of course I avoided the subject in conversation, but I saw very clearly how unpleasant the news was which I brought. So it has been everywhere. This is a sort of thing that can be neither denied, palliated, nor evaded; the disasters of the rebels are unredeemed by even any hope of success. Accordingly the emergency has produced here a mere access of spite, preparatory (if we suffer no reverse) to a revolution in tone.

It is now conceded at once that all idea of intervention is at an end. The war is to continue indefinitely, so far as Europe is concerned, and the only remaining chance of collision is in the case of the iron-dads. We are looking after them with considerable energy, and I think we shall settle them.

It is utterly impossible to describe to you the delight that we all felt here and that has not diminished even now. I can imagine the temporary insanity that must have prevailed over the North on the night of the 7th. Here our demonstrations were quiet, but, ye Gods, how we felt! Whether to laugh or to cry, one hardly knew. Some men preferred the one, some the other. The Chief was the picture of placid delight. As for me, as my effort has always been here to suppress all expression of feeling, I preserved sobriety in public, but for four days I’ve been internally singing Hosannahs and running riot in exultation. The future being doubtful, we are all the more determined to drink this one cup of success out. Our friends at home, Dana, John, and so on, are always so devilish afraid that we may see things in too rosy colors. They think it necessary to be correspondingly sombre in their advices. This time, luckily, we had no one to be so cruel as to knock us down from behind, when we were having all we could do to fight our English upas influence in front. We sat on the top of the ladder and did n’t care a copper who passed underneath. Your old friend Judge Goodrich was here on Monday, and you never saw a man in such a state. Even for him it was wonderful. He lunched with us and kept us in a perfect riot all the time, telling stories without limit and laughing till he almost screamed.

I am sorry to say, however, that all this is not likely to make our position here any pleasanter socially. All our experience has shown that as our success was great, so rose equally the spirit of hatred on this side. Never before since the Trent affair has it shown itself so universal and spiteful as now. I am myself more surprised at it than I have any right to be, and philosopher though I aspire to be, I do feel strongly impressed with a desire to see the time come when our success will compel silence and our prosperity will complete the revolution. As for war, it would be folly in us to go to war with this country. We have the means of destroying her without hurting ourselves.

In other respects the week has been a very quiet one. The season is over. The streets are full of Pickford’s vans carting furniture from the houses, and Belgravia and May Fair are the scene of dirt and littered straw, as you know them from the accounts of Pendennis. One night we went to the opera, but otherwise we have enjoyed peace, and I have been engaged in looking up routes and sights in the guide book of Scotland. Thither, if nothing prevents and no bad news or rebel plot interferes, we shall wend our way on the first of August. The rest of the family will probably make a visit or two, and I propose to make use of the opportunity to go on with Brooks and visit the Isle of Skye and the Hebrides, if we can. This is in imitation of Dr. Johnson, and I’ve no doubt, if we had good weather, it would be very jolly. But as for visiting people, the truth is I feel such a dislike for the whole nation, and so keen a sensitiveness to the least suspicion of being thought to pay court to any of them, and so abject a dread of ever giving any one the chance to put a slight upon me, that I avoid them and neither wish them to be my friends nor wish to be theirs. I have n’t the strength of character to retain resentments long, and some day in America I may astonish myself by defending these people for whom I entertain at present only a profound and lively contempt. But at present I am glad that my acquaintances are so few and I do not intend to increase the number.

You will no doubt be curious to know, if, as I say, I have no acquaintances, how I pass my time. Certainly I do pass it, however, and never have an unoccupied moment. My candles are seldom out before two o’clock in the morning, and my table is piled with half-read books and unfinished writing. For weeks together I only leave the house to mount my horse and after my ride, come back as I went. If it were not for your position and my own uneasy conscience, I should be as happy as a Virginia oyster, and as it is, I believe I never was so well off physically, morally and intellectually as this last year.

I send you another shirt and a copy of the Index, the southern organ, which I thought you would find more interesting this week than any other newspaper I can send. It seems to me to look to a cessation of organized armed resistance and an ultimate resort to the Polish fashion. I think we shall not stand much in their way there, if they like to live in a den of thieves.

July 23—Left at 5 this morning, went through Front Royal—seventeen miles to-day. Waded the south and north prongs of the Shenandoah River. We then took the road to Mananas Gap, marched three miles, when we met the enemy and had brisk firing until dark. Their line is very strong. They advanced in two lines in very fine order. When they got within range of our guns we opened on them, and they scattered like bluebirds. We had a beautiful view of this fight, as we are on the mountain. Neither of the armies can move without being seen by the other. Our corps of sharpshooters has been formed again since a few days ago. We were sent to the support of the other corps. We were within twenty yards of the enemy’s line until midnight, when we fell back in good order.

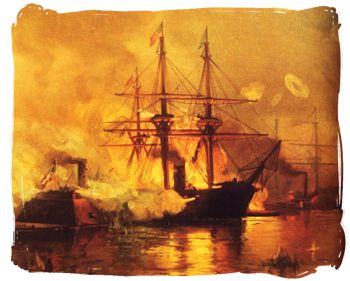

July 23d. At six o’clock this morning, steamer Eugenie came up and anchored ahead of us, having our top-gallant and royal masts, also yards and rigging on board, which she had been to Pensacola for; at nine inspected crew at quarters; at nine thirty, sent our launch to steamer Eugenie, and brought on board our spars. Engaged repairing rigging during the afternoon or remainder of this day—got main top-gallant and royal yards in the rigging and painted them, and employed in sending aloft top-gallant rigging and getting top-gallant masts ready to send aloft. Weather cool and pleasant. Men very busy.

July 23, 1863.—We arrived in Kingston, Georgia, last evening, and put up at one of the hotels; we paid three dollars each for breakfast and a night’s lodging; paying it out of the donation money, of which we have still some on hand. Dr. A. called early this morning; he is post surgeon, a fine-looking old gentleman, and a man highly respected for his surgical abilities. He was left in charge of our wounded at Murfreesboro, and, I am told, has written a valuable book on surgery, from his experience at that place. He is a man of sterling principle, but a little eccentric. The first information we received from him was, that he did not approve of ladies in hospitals; that was nothing now from a doctor, but we were a little taken aback to hear it said so bluntly. Ho then told us his principal objection was, that the accommodations in hospitals were not fit for ladies. We assured him he need give himself no uneasiness on that score, as we were all good soldiers, and had been accustomed to hardships.

He then said the two girls we brought from Chattanooga could not remain as servants, as he intended having a number of negroes on the place, and that would be putting them on equality; and if we could not retain them in some other capacity, they would have to be dismissed. There is always plenty of sewing to be done in the hospital, and we knew we could give them employment in that department.

He also told us that he wished us all to eat at the officers’ table, with himself and the assistant surgeon, as he thought a table was not fit to eat at where there were no ladies. We did not object to that plan till we had given it a trial.

We were escorted to the house which we now occupy. It consists of two small rooms on the ground floor. We are about a square and a half from the dining-room and kitchen; so when Drs. A. and H. called to take us to dinner, we made quite a procession. On the way, Dr. A. informed me that he was a strict disciplinarian, and as I had charge of every thing in the domestic line, if there was not a good dinner that day, he would call me to account. I laughed and told him, if he talked in that way, I should think him a real Pharaoh, as 1 had not even had time to look around me.

We had an excellent dinner—a much better one than we had eaten in many a day. The two girls looked as if they felt themselves sadly out of place, but we are in the army, and must obey orders.

This is quite a small place, and there does not seem to be a large building in it, with the exception of the churches and hotels. Of the latter there are no less than four. It is in Cass County; is on the Western and Atlantic railroad, sixty-two miles north-west of Atlanta, and at the junction of the Rome branch railroad; it is not quite twenty miles from the latter city.

Dr. A. has been here for some time, and has converted some old stores into very nice wards, which will do very well for winter, but are entirely too close for summer.

23rd. Thede got on order a secesh saddle. Gave up my mare to Dr. Smith. Gave me an old plug. Traded her for a pretty brown mare, $25 to boot. Jeff gave us a shave all round. Apples. Cleaned revolvers. Traded and gave $5 for a silver mounted one. Ordered to march tomorrow with Com. horses to Cinn.