July 28th. Commences with pleasant weather and light westerly winds. The following is what has transpired this day:—At eight A. M. the U. S. steamer Virginia arrived; at three P. M. the Monongahela came down the river and anchored off the Richmond’s starboard quarter. Ship’s company engaged getting ship ready for sea.

Sunday, July 28, 2013

28th. Passed the night very quietly in guard house. Deserters and drunken men filled the room. Novel place. Before noon went down to Provost and saw Mrs. Mills. At 3 P. M. we took the train under guard to Cincinnati. Lawyer Hall came with S. R. N. Pleasant ride down. Reached the city and after marching half an hour took quarters on fifth floor of Military Prison. Felt sorry for S. R. and friends. Felt jolly enough myself. Floor filthy and no blankets.

Tuesday, 28th.—At Atlanta, 1:30 A. M. Left Atlanta, at 7 A. M. At Tunnel Hill, 3 P. M., where Brother I. L. met me with buggy; found all well except brother; his wound doing very well.

28th.—The girls are in Richmond, staying at Dr. G’s. They went in to attend a tournament to be given to-day by General Jenkins’s Brigade, stationed near Richmond; but this morning the brigade was ordered to go South, and great was the disappointment of the young people. They cannot feel as we do during these gloomy times, but are always ready to catch the “passing pleasure as it flies,” forgetting that, in the best times,

“Pleasures are like poppies spread:

You seize the flower, the bloom is shed.”

And how much more uncertain are they now, when we literally cannot tell what a day may bring forth, and none of us know, when we arise in the morning, that we may not hear before noonday that we have been shorn of all that makes life dear!

Camp near Warrenton, Va.,

July 28, 1863.

Dear Parents:—

It is seldom that I have written so few letters after a great battle as I have since the battle of Gettysburg. I have had two good reasons, one that we have been almost constantly on the move since, and the other that I have not been able to write. I have said but little about it, not wishing to cause you anxiety, but for three weeks I have had all I could do to keep along in my place. The night of the 4th of July it rained tremendously, and I had little shelter and lay in water half an inch deep all night. I was too much exhausted to stand up or even to keep awake. I was wet through most of the time for a week after, and a very bad diarrhea set in which destroyed my appetite and made me very weak. I would not take doctor’s stuff, thinking I could wear it off as I always have done, but it held on well this time. At last I did take a physic, and when we got into Manassas Gap the blackberries cured me up. I feel more like myself to-day than I have for almost a month. Nothing but my horse and a firm resolve to hold out to the last has kept me out of the hospital this time. I could not have walked half a mile a good many days that I have rode fifteen. I could have found time to write a good many more letters if I had been well, but as it was, as soon as we stopped I could do nothing more than lie down and rest.

I received your letters of the 10th at Rectortown, on the Gap railroad. I was very glad to see them, the first I had heard from you since you received news of my safety. Two things in it surprised me—one was the direction—that letter was two days in the regiment before I got it because it was directed to the regiment. Always direct, “Headquarters Third Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Washington, D. C.” Don’t put on regiment or company. Headquarters mail is pushed right through, when the large bags don’t come, and very often I don’t go to the regiment for three or four days, and any mail sent there waits till I come.

The other surprising thing was—”do come home.” As many soldiers have been spoiled by just such letters from anxious parents as any other way. Mother writes, “Come home; I do so want to see my boy if only for a little while.” Soldier writes that he would come if he could, and begins to think about it and chafe and fret at his bonds till he worries himself homesick and isn’t worth a row of pins. You have never said much to me of that sort, but it would not make much difference if you did. I made up my mind when I enlisted to stay till the matter was settled or my three years served out. As long as I am well I wouldn’t come home if I had a furlough in my hand, which, I might remark, is a place very difficult to get a furlough in nowadays. If I were sick and in a hospital, I should perhaps try to get home, but not while I stay in the field. This off and on soldiering is hard on a person’s nerves. You will be the more glad to see me when I have been gone three long years.

I am very glad, Mother, that you like your new home so well. Aristocracy in these days ought to be at a discount. Shoddycracy is pretty large in New York, they say, the hideous offspring of the monster war. I am afraid the army would not suit you very well on that very account, supposing you could be in it. One of the officers of my own company can write no more than his own name, and that scarcely legible, yet military rules require me always to touch my cap when I speak to him, as an acknowledgment of his superiority.

You ask if I have any fruit. I have had but little. Cherries have been plenty in the country we passed through, but I have had little chance to get them. We never know at what minute we shall move. Orders come at daylight, at sunset, at noon, at midnight, “Prepare to march immediately,” and the first thing is—”Bugler sound the general” (the call to strike tents), so that I am obliged to be always at my post. The men in the regiments scatter out in the country, get fruit and buy bread and pies, but I can’t leave and so don’t get much. Blackberries I have had a better chance at, for they are everywhere. You may know how close I am kept when I tell you that I have been trying for a month to see Edwin Willcox, and, though he has slept within half or a quarter of a mile from me a good many nights, I have never seen him yet.

I wish you would put up two or three cans of fruit for me, so that, if we go into winter quarters again, you can send them to me. Fruit is something I miss as much as anything in the army. The sutler makes no bones of charging seventy-five cents for a tumblerful of jelly.

I wish you would send me, if you can get it, next time you write, a little camphor gum and assafœtida. If you cannot get the latter send the camphor alone, just a little, what you can put in a letter. I want it to drive away lice.

In regard to that expression that shocked you so much. I am sure I meant nothing irreverent, and, as Father remarked, it is a common expression in the army for a hot reception of the enemy. Used in that sense, it does not seem so inappropriate, for such fighting, such bloody carnage belongs more to demons than to this fair earth. No reference to anything in their condition after death was intended. That is not for us to judge.

I had intended to write more, but a heavy shower is coming up for which I must prepare, and I shall have no more time before the mail closes.

We expect to rest here a little while, hope to, at least.

July 28 — I arrived at home today.

—- End of W.B. Clack’s diary entries from Vicksburg fight and trip home —

July 28. — Went this morning to the 2d Massachusetts and saw Bill Perkins, George Thompson, and Francis. From there I went to General Greene’s headquarters, and saw Charley Horton.[1] Went to Gordon’s division of the Twelfth Corps, and saw Gray, Motley, and Scott.[2] When I came back, I found that the general had gone to Rappahannock Station. Nothing new. Weather showery in the afternoon.

[1] Charles P. Horton, Harvard 1857.

[2] Henry B. Scott, my classmate.

Vicksburg, Tuesday, July 28. Very warm and oppressive. Suffered severely from my finger. I am afraid I am going to have a felon on it. Did not take care of my team. Battery M, 1st Missouri returned from their Jackson expedition, forty on the sick list, being obliged to use their mule drivers to park their battery.

by John Beauchamp Jones

JULY 28TH.—The rumor that Gen. Lee had resigned was simply a fabrication. His headquarters, a few days ago, were at Culpepper C. H., and may be soon this side of the Rappahannock. A battle and a victory may take place there.

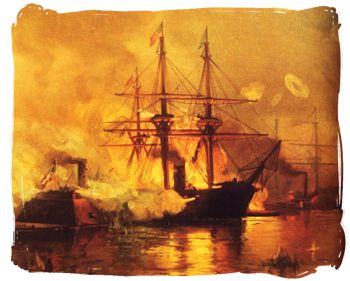

Col. J. Gorgas, I presume, is no friend of Pemberton ; it is not often that Northern men in our service are exempt from jealousies and envyings. He sends to the Secretary of War to-day a remarkable statement of Eugene Hill, an ordnance messenger, for whom he vouches, in relation to the siege and surrender of Vicksburg. It appears that Hill had been sent here by Lieut.-Gen. Holmes for ammunition, and on his way back to the trans-Mississippi country, was caught at Vicksburg, where he was detained until after the capitulation. He declares that the enemy’s mines did our works no more injury than our mines did theirs ; that when the surrender took place, there were an abundance of caps, and of all kinds of ordnance stores; that there were 90,000 pounds of bacon or salt meat unconsumed, besides a number of cows, and 400 mules, grazing within the fortifications ; and that but few of the men even thought of such a contingency as a surrender, and did not know it had taken place until the next day (5th of July), when they were ordered to march out and lay down their arms. He adds that Gen. Pemberton kept himself very close, and was rarely seen by the troops, and was never known to go out to the works until he went out to surrender.

Major-Gen. D. Maury writes from Mobile, to the President, that he apprehends an attack from Banks, and asks instructions relative to the removal of 15,000 non-combatants from the city. He says Forts Gaines and Morgan are provisioned for six months, and that the land fortifications are numerous and formidable. He asks for 20,000 men to garrison them. The President instructs the Secretary, that when the purpose of the enemy is positively known, it will be time enough to remove the women, children, etc.; but that the defenses should be completed, and everything in readiness. Bat where the 20,000 men are to come from is not stated—perhaps from Johnston.

Tuesday, 28th—We started early this morning and though it was hot and sultry, we reached Vicksburg at 10 a. m. So we finally entered Vicksburg after more than eight months in trying to take the place. In the afternoon we moved out a few miles to the north of town and went into bivouac. While in Vicksburg we saw some of the paroled prisoners leaving for their homes. They were indeed sorrowful-looking beings—all in rags and without food; yet they were ready to fight for their cause to the bitter end.