August 7.—The Twenty-first and Twenty-fifth regiments of Maine volunteers, passed through Boston, Mass., on their return from the seat of war.—President Lincoln declined to suspend the draft in the State of New-York, in accordance with the request given by Governor Seymour in his letter of August 3.

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

August 7, Friday. Went on board of steamer Baltimore Wednesday evening in company with a few friends, for a short excursion. My object was to improve the time set apart for Thanksgiving in a trip to the capes of Chesapeake, and there imbibe for a few hours the salt sea air in the hope I should thereby gather strength. Postmaster-General Blair, Governor Dennison of Ohio, Mr. Fox, Mr. Faxon, Dr. Horwitz, and three or four others made up the party. We returned this A.M. at 8, all improved and invigorated.

The papers contain a letter of mine to Senator Sumner, written last April, denying the reckless falsehood of John Laird, made on the floor of Parliament, to the effect that I had sent an agent to him or his firm to build a ship or ships. There is not one word of truth in his statement. Had I done so, is there any one so simple as to believe the Lairds would refuse to build? — those virtuous abolitionists who, as a matter of principle, would not use the product of slave labor, but who for mercenary considerations snatched at the opportunity to build ships for the slave oligarchy? But I employed no agent to build, or to procure to be built, naval vessels abroad of any description. My policy from the beginning was not to build or have built naval vessels in foreign countries. Our shipbuilders competed strongly for all our work. The statement of Laird is mendacious, a deliberate falsehood, knowingly such, and uttered to prejudice not only the cause of our country but of liberty and human rights.

A friend of Laird’s, an abolitionist of Brooklyn, New York, tried to secure a contract for Laird, but did not succeed. When Laird found he could secure no work from us, he went over to the Rebels and worked for them. After making his false statement in Parliament, fearing he should be exposed, he wrote to Howard, his abolition friend in Brooklyn, begging to be sustained. Howard being absent in California, his son sent the letter to Fox, through whom they tried to intrigue in the interest of Laird.

The President read to us a letter received from Horatio Seymour, Governor of New York, on the subject of the draft, which he asks may be postponed. The letter is a party, political document, filled with perverted statements, and apologizing for, and diverting attention from, his mob.

The President also read his reply, which is manly, vigorous, and decisive. He did not permit himself to be drawn away on frivolous and remote issues, which was obviously the intent of Seymour.

Letter No. XII.

Camp Near Fredericksburg, Va.,

August 7th, 1863.

My Precious Wife:

We have just heard of the death of Colonel B. H. Carter. He was wounded at Gettysburg—twice in the leg, and in the face, and left in the hands of the enemy. I wrote you not more than a week ago quite a long letter by Captain Hammon, telling you all about my Pennsylvania trip, a full narrative of which could be made quite readable, but I am not conveniently situated for thinking or writing, so as to render the undertaking feasible. I am having a pretty hard time of it, but heaven is blessing me continually with good health, and I believe will save me to the end.

You must not be uneasy about me when you do not hear from me. I have received but one letter from you since I left home, yet I am satisfied that all is well, and, strange to say, I have no desire to return home while the war lasts. I believe this disposition has been especially vouchsafed me in order that I may be fully prepared for all the hardships that befall me. Since the fall of Vicksburg I have not had much hope of hearing from you, though, to our suprise, yesterday, Coella and Macon Mullens received letters of the 5th and 6th of July. This has encouraged me to hope for one from you. I have written you a great many letters from different points. You must not be uneasy if you hear of me being destitute or in need of anything. A soldier can not carry enough with him on a march to make him comfortable. Another hope and desire you must give up; it is almost impracticable and hopeless to attempt to recover the body of a private soldier killed in battle, so don’t think about this; I can rest one place as well as another. All the Waco boys are writing to-day, as notice has been given that a Mr. Parsons will take them to Texas. Do all you can to keep your mind employed and your face in smiles. All will yet be well for us. Pray for me, and if I am taken from you, it will be all right. I trust in God. Kisses for the children.

Your husband, faithfully ever,

John C. West.

Colonel Lyons.

Fort Donelson, Aug. 7, 1863.—I am going to Clarksville on the first boat, to consult with Colonel Bruce about an expedition from both places through the country to Waverly. I had to obtain leave from Nashville before I could go—so strict are the orders on this subject.

The guerillas destroyed the telegraph office night before last at Fort Henry. There are no troops there now. Our mounted infantry chased them ten miles, but failed to catch them.

August 7 — We were on outpost picket until sunset, and were relieved then by the second section of our battery. We came back on reserve and camped quarter of a mile west of Brandy Station. From our picket post we saw the Yankee line of pickets to-day, which was only about a mile from our post.

We had a hard thunder-shower this evening while we were returning from picket; rain fell in torrents, which soaked us all over.

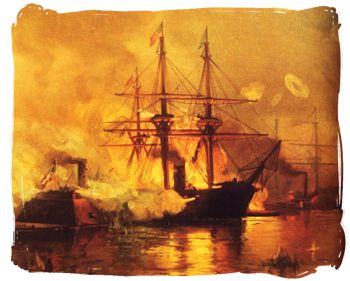

Aug. 7th. Commences, and until four A. M. pleasant weather; from four o’clock to eight o’clock braced sharp up on port tack; all plain sail set to royals; made a sail off starboard bow, and one off starboard beam; from twelve to four P. M. exercised the fore and main royal yardsmen in furling and loosening royals; at two o’clock set the foretop-gallant and topmast studding sails; at three o’clock took them in; passed a brig bound the same course; at six thirty laid the yards square, and took in all fore and aft sails except the jib; braced sharp upon starboard tack, and set foretop-gallant studding sails; at six forty-five inspected crew at evening quarters; from eight to midnight all plain sail set to royals.

August 7.—I intend leaving to-day for Chattanooga.

This morning I sent for Dr. A., and told him that it was impossible for us to get along without more servants; and I told him further that I knew of some who could be hired, and asked his consent; but he would not give it. So I then told him that Mrs. W. and myself would leave. At this he became quite angry, and said he could not compel us to remain, but since he had hired us ladies, he would pay us for the time we had been there. The latter part he said with emphasis, and then left me. Had he remained longer, I should have informed him that when we “hired” ourselves, we were not aware it was to him, but to the same government which had “hired” him.

I am beginning to think that we were spoiled in the Newsom Hospital; but I should hope that there are not many surgeons in the department such as Dr. A. If there are, it is not much wonder that so few ladies of refinement enter them.

I ask but one thing from any surgeon, and that is, to be treated with the same respect due to men in their own sphere of life. I waive all claim for that due me as a lady, but think I have a right to expect the other. I scarcely think that Dr. A. would dared to have spoken to one of his assistant surgeons as he did to me.

All this has made me feel more for our proud-spirited men, who I know have to endure insults from the petty officers over them. Well, these trials must be endured for a little while; they will soon, I trust, be over with; and then, it is for the cause we have to put up with them.

7th. Spent the morning reading and doing chores. In the afternoon made an hour’s call on Fannie. Engaged Mr. Turner’s horse and rode from 7:30 till 9 with Thede and Minnie. Very pleasant time. Went to George Fairchild’s room and read class letters. Borrowed one from Burrell.

August 7th, 1863.

It was with a bounding heart, brimful of gratitude to God, that I stepped on board the Dakota and bade farewell to Haines Bluff on the second day of August. We have three hundred sick and wounded on this boat and are short of help. Quite a number who started as nurses are sick. Four men died the first night. We ran the boat ashore, dug a grave large enough for all, and laid them in it, side by side. Our Chaplain read the burial service, and we hastened on board to repeat the ceremony, the next morning, for some one else. It seems hard—even cruel—but it is the most solemn burial service I ever witnessed. Nine have died since we started, and one threw himself overboard in the frenzy of delirium and was drowned. We kill a beef every evening. Two nights in succession the best part of a hindquarter has been stolen. The boat hands were questioned, and a huge Irishman acknowledged the theft. He was court martialed and sentenced to be “banked.” The boat was stopped opposite a wilderness. No human habitation was in sight. He was forced to pack his bundle, take to the woods and run his chance with hunger and the Rebels.

As we were running leisurely along, about 3 o’clock in the afternoon of yesterday, my curiosity was aroused by our boat running suddenly against the shore and sticking there. All hands were called, and, with the aid of soldiers, she was soon shoved off, and on we went again. A Sergeant asked the Mate why we landed there. His reply was, “Something wrong in the wheel house.” One of our boys asked a darkey the same question. “Well, boss, I ‘specs dey see a rabbit ober dere, an’ t’ink dey kotch ‘im.” Soon after, as two comrades and myself were sitting in the bow enjoying the cool breeze, my attention was attracted by the glassy stillness of the water in front of us. Pointing to the right, I said, “Yonder is the safe place to sail.” The words had scarcely left my mouth when we felt a sudden shock, the bow of the boat was lifted about two feet, a full head of steam was turned on, which carried us over the obstruction. We had “struck a snag.” Soon after, we anchored for the night, as the pilot was “too sick” to run the boat.

The sick from our regiment are doing well. I never saw wounded men do so nicely. Of five who came as nurses, four are on the sick list. As for myself, I have not been so well in years.

Friday, 7th—It is quite sultry today. There is no news of any importance. The Sixteenth Iowa received their pay today.