Our work was done. The regiment languished for two or three weeks, — first upon the bluff; then upon a hot, pestilential plain, far back within the fortress. Day by day, men fell sick of fever, or worn out for the want of proper food. Day by day, we laid away the dead; and it was plain more must die, unless we could soon go northward.

At length, the forenoon of the 23d of July, while we were burying poor Spencer Phelps, dead of terrible fever just at the moment when relief was at hand, the transport touched at the Levee, which was to take us North. At dusk, we left the tents and the graves, the long parapet with our rifle-pits beyond, and the barren, sun-baked bluff. We marched aboard, a nerveless, debilitated company, too weak and sick to show joy even at going home.

Grosvenor, indeed, my good friend, a high-minded patriot, whose great spirit had carried his feeble body through all our exposures, though pale and haggard, went from man to man, shaking-hands. He lay down at night, spreading out his blankets with his old comrades. In the morning, his couch lay as he had spread it; but he was gone, and the eyes of no man have rested upon him since. His was a brave and knightly soul. No doubt he rose in the night, too, exultant, perhaps over the brighter prospects of our great cause, and over the thought that hardship honorably borne was soon to be over, to sleep. The moon, about full, floated gloriously before him in the heavens, among the summer clouds, as the “Sangreal, with its veils of white samite,” floated before Arthur’s pure-souled knights. A misstep with his. weak limbs, and he fell overboard into the flood. So our good friend must have perished.

Steadily we pushed northward. A large space, where it was most airy, was given up for a hospital, and crowded with the sick. Here was my post at night, from seven to one. One night, three worn-out soldiers gave up the ghost; but the wind, as we drew forward, blew more cool, and the air of home began to have its effect.

We looked off upon Natchez and battered Vicksburg; upon gunboats patrolling, and at anchor off dangerous shores. Then came Memphis; and in a day or two, a week after we had begun our voyage up those long leagues, we reached Island Ten and Columbus, — the hostile strongholds of two years before.

We left nearly a score of our more deathly sick to the Sisters of Charity at Mound City; then on through ”Egypt,” where they did not care for us; across through loyal Indiana and Ohio, where they cheered and clasped us, and only blamed us because we had sent no word of our coming. Flourish, little Marion! where every villager came running to us, who were so worn and hungry, with a well-filled basket; and blessings on generous Buffalo! city of prodigious gains and prodigious munificence, where, on Sunday morning, a congregation and their shepherd held service at the depot, ministering with tearful eyes to the sallow and fever-smitten multitude.

And now we are nearing home. Hark! it is my own church-bell, ringing welcome. Here are the familiar faces at last. Old Cruden and venerable Calmet welcome their master from their shelves; and ere long, washed and refreshed, the soldier falls on his knees, by the side of his own sweet, white bed, to thank God for his mercies.

The Banks campaign of the spring and early summer of 1863 is coming to be looked upon as a masterpiece of strategy. As yet, but little has appeared in print about it. It ought, however, to interest the military student and the general public. Facts, I think, will support the interpretation of the campaign, which I propose to give. If the view about to be presented is correct, to Gen. Banks, in addition to his former fame, is due the glory of being a mighty leader of armies.

Gen. Banks was sent to Louisiana to hold and govern the territory which had already been conquered by Butler and Farragut, and to restore the Federal authority in regions still under the rebel domination. In the way of offensive operations, the special task given him to perform was to co-operate with Grant in re-opening the Mississippi. Vicksburg and Port Hudson were the two obstacles to be overcome. To Grant was intrusted the reduction of the former; to Banks, the capture of Port Hudson.

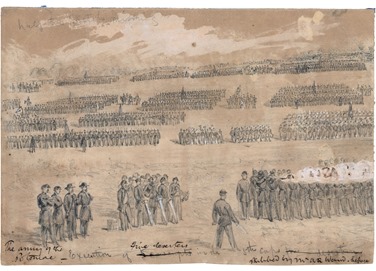

During the inclement weather of the winter, the army was arriving. The regiments, as they came, went into camp, and were vigorously drilled. In March, when the heavy rains had ceased and military operations became possible, Banks was ready to take the field. His force consisted only of the Nineteenth Army Corps. A good part of this force were “nine-months’ men,” whose terms of service expired during the first part of the summer. Whatever was done, must be done before midsummer.

At this time, Gardner held Port Hudson with a force equal to, or perhaps greater than, the army which Gen. Banks could bring against him. To rush at once upon the enemy, within his strong intrenchments, would have been to incur certain and bloody defeat. It was an occasion for strategy. Port Hudson could be reduced, if Gardner could be led to send away a considerable part of his garrison; and if, at the same time, it could be so managed, that the remnant left should be short for supplies, so that protracted resistance would be impossible. How to accomplish this was the problem before the general, in the beginning of March, when he prepared for active operations.

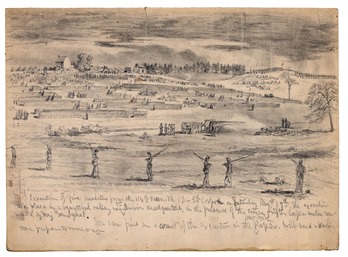

The first operation of the campaign was directed toward cutting off the river communication of the garrison, by which they could receive supplies and re-enforcements. The 13th of March, we set out from Baton Rouge for Port Hudson. At dusk of the 14th, the reader of the foregoing pages will remember, we were pushed up to within easy cannon-range of the rebel batteries; while field-artillery fired and manoeuvred as if a rush were to be made at once upon the parapet. We expected a land-attack; the enemy expected it. A bright reb, whom I met, during the truce on the morning of the capitulation, between their rampart and our rifle-pits, told me, that, so confident were they that night of a land-attack, the cannoneers on the bluff were off their guard. They did not see the fleet stealing silently past, until the vessels at the head were pretty much out of danger, up the stream. If they had seen them, they could have kept them down as they did the ships farther back.”The next day, as I stood on the bold Port-Hudson bluff, and saw the immense guns which the rebels had planted on the brow, with delicate sights just above the enormous muzzles, and well-stored magazines, and ovens for hot shot close at hand, I could not help believing what the rebel had told me. With those cannon, hot shot and shell could be cast, almost with the precision of rifle-balls, at objects passing below. If the cannoneers had kept sharp watch, the “Hartford” and “Albatross,” both wooden vessels, could not have passed. It was precisely that thing the general was manoeuvring after, — to induce the garrison to look for a land-attack; whereas the object he had in view was to get these powerful vessels above the fortress to cut off the river communication. It was the artifice, precisely, of a skilful boxer, who makes a feint with his right hand, then puts in the blow in earnest with his left. The stratagem was successful. The general, no doubt, wished to pass a stronger force of vessels above the fortress; but the two proved sufficient. The rebels had nothing on the stream to cope with them in fair fight, and Farragut was too sagacious and prudent to be entrapped. The “Mississippi,” indeed, was lost; but one old frigate was a small price to pay for so substantial an advantage.

The next operation of the campaign was to manoeuvre in such a way as to induce the rebel commanders to believe, that Port Hudson, after all, was not the threatened point. Now that the river was in our possession, the great garrison at Port Hudson would soon be embarrassed for supplies; and, if Gardner and Pemberton could be induced to believe that Banks had some project elsewhere, it would be the natural thing for them to withdraw a portion of the force from the distressed stronghold, and send them, by land, where they fancied the troops could be of more service.

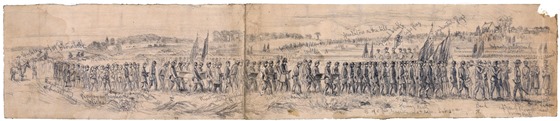

Banks proceeded without delay. At the end of March, we embarked on transports, and went southward from the rebels, toward New Orleans. Landing at the Bayou La Fourche, we marched westward, and, in a week or two, began the raid through the back country, from Brashear City to Alexandria on the Red River. The inferior rebel force in this region was dissipated by our hasty rush; a vast amount of cotton and sugar were captured; and supplies were seized, which might possibly have found their way into Port Hudson, escaping the vigilance of the “Hartford” and “Albatross.” But the most important end accomplished was this,—and it was, no doubt, the end which the general had mainly in view, — it completely misled the rebel generals as to his real designs.

The young rebel colonel, chief of Gardner’s staff at Port Hudson, the night after the capitulation in July, rides over to the Federal camp to see his old friend and former companion-in-arms, Col. G —, of the —th Mass. An old friend of mine, a distinguished young officer of the regiment, is present at the interview, and sits up himself with the rebel colonel, till midnight, talking over past events. Next time I see my friend, he tells me about his talk. One thing is this: This officer says, that, when Banks was at Alexandria, it was believed, on the rebel side, that Port Hudson was no longer threatened; that, at that time, Lieut-Gen. Pemberton sent word from Vicksburg, to his subordinate, Gardner, that Port Hudson was not in danger, and that he might send elsewhere part of his army. Gardner did so; and, when he was weakened by sending off a large portion of his force, suddenly Banks, on the Red River, put his army upon transports, and Port Hudson was invested, before a man of those who had been sent away could be recalled.

“Oh,” said the rebs to us when the fortress fell, “if you had only attacked us when you came up in March. when we were ready for you!” But that was precisely what Gen. Banks was too wise to do. Instead of that, he had preferred to manoeuvre so as to induce the rebel leaders to reduce the garrison, and to cut off their supplies of provisions.

The field of all this manoeuvring was very extensive. The Fifty-second Regiment marched more than three hundred miles while it was being done, and a portion of the army accomplished still more. Well do we remember what ache and sweat it cost us! But it was vigorous to the extent of human endurance, and perfectly successful; for at the end of May, when the sudden investment of Port Hudson took place, the place contained but a few thousand troops, with provisions for only a few weeks.

The third and closing operation of the campaign was the siege of Port Hudson. During this siege, two assaults were made upon the rebel works, — on the 27th of May and the 14th of June. Both were bloody; both were unsuccessful as assaults: and Gen. Banks has been blamed sometimes for having “mismanaged” them, sometimes for having suffered them to be made at all.

As to the charge of mismanagement. It should be remembered, that no military undertaking is more critical than an assault upon a well-defended fortress. In 1811, Wellington was twice repulsed at Badajoz, with prodigious loss; and in 1799, at Acre, Napoleon himself rushed seven or eight times in vain against the works defended by the British and Turks. Certainly it would be rash to say, simply because an assault was unsuccessful, that it was mismanaged. The opinion of competent military critics is alone of value upon this point. The writer is far enough from pretending to such a character. We used to hear, at Port Hudson, that the assaults failed from lukewarmness on the part of subordinates; from the irremediable embarrassment arising from the early and unexpected fall of officers holding important commands; and from the circumstance, that portions of the attacking force lost their way. To say the least, it is as probable that some such cause as this prevented success, as that there was want of skill in planning the attacks.

Gen. Banks has been blamed for having suffered the assaults to be made at all. Since an assault is so critical an affair, perhaps nothing is sufficient to justify one, but some great strait in which a general is placed. A siege is far safer and more certain, and ought, no doubt, to be preferred, when there is time. Was Gen. Banks in such a strait as to justify him in trying to storm Port Hudson? It is hard to see how a general can be in a much closer corner than was Gen. Banks at the end of May. At the outset of the campaign, his force was small, in view of the objects to be accomplished. The vigorous operations which took place at once had diminished this force very largely. The hot season had already begun; during which, sickness was sure to prevail. Moreover, the time of the “nine-months’ men” was on the point of expiring. Is it strange Gen. Banks felt driven to even desperate expedients?

The assaults failed in their main object of taking the fortress, but still secured us some advantages. Each time, numbers of rebels fell, and important ground was gained close under the hostile parapet.

The siege was pushed as operations had been pushed from the beginning. Farragut kept watch above and below on the river, and no food could reach the half-starved garrison. From land and stream poured in a constant fire of shot and shell, while sharpshooters sent their volleys day and night. At length, the place fell. It was high time: for the nine-months’ regiments were beginning to mutiny; New Orleans, which was held by a small force, was seriously threatened; and the whole army, under the burning heats, was fast sinking away. Out of our company of ninety, scarcely twenty were on duty at last. The whole regiment was diminished in the same proportion, and the men counted as effective were generally far below the standard of health; yet there were few stronger regiments than ours. That the fall of Vicksburg, which took place a few days previous, only hastened the fall of Port Hudson by a day or two, we have the testimony of the rebel leaders, and the explicit declaration of Gen. Grant himself. The Nineteenth Army Corps claim for their general the full glory of the capture, — a success accomplished with a small comparative force, within a comparatively short time, under unfavorable skies. We claim for our leader the superlative merits of almost unexampled vigor, sagacity, courage, and persistence.

The day after the surrender, I saw the general ride on his black steed, down the bluff, on his way to the “Hartford,” to exchange congratulations with his brave and skilful coadjutor, the admiral. He was haggard and pale, as were his men; but strong and exultant. So he rode, — the foremost man of New England; perhaps the foremost man of the land: and so, I can believe, rode Marlborough, after Blenheim; and Prince Eugene at Belgrade.

During the past year, I have seen much of human nature,—often a very rough side of it. In our own regiment were a large number of men of such age and character as are not usually found in the position of private soldiers; but we had, besides these, a proportion of “rough characters.” Then, again, in organizations less favored than ours, with which we were associated, there was ample opportunity of meeting with those whom society calls very much debased. I met such men under circumstances when many of the ordinary restraints of life were taken off, so that their true natures could come out more fully. What have I learned? To put as much confidence in men as ever; to believe in the intrinsic goodness of the human heart. Indolence, cruelty, sensuality, meanness, are the things men invariably detest, and what they blame. Mercy, liberality, truth, kindness, are what they invariably commend.

Much evil there is among the rank and file, as there is among those higher in position. I have seen want of patience, want of honesty, want of temperance. I have seen gambling and ill-temper, and know how foul the air of a camp is with coarseness and blasphemy. But this I have not seen: the man who liked or would commend selfishness; the man who disliked or would blame unselfishness. One does not learn to think less of human nature from contact with “rough men,” however it may be from contact with those at the opposite social extreme. Often they do not imitate what they admire; often they do not avoid in their own conduct what they detest in others: but this is true, that the human instincts are always fixed in a love for good, in a hatred for bad. In the society of the low, as in every human society, there is but one rule for securing enduring popularity, — “Be unselfish.”

I have known men, rough in language and manners; judged by our conventional standards, thoroughly unsanctified; perhaps they hardly ever saw the inside of a church, or breathed an audible prayer, though their talk was full of oaths: yet they would do noble things. They would help others generously; they would bear privation cheerfully; and I have known them, in a time of pestilence, to watch, day and night, with patients sick of contagious diseases, when the camp was full of death. They watched until they grew sick; then, after they were sick, until their lives were in peril. I have heard the lips of dying men bless them.

The thought of the beautiful poem of “Abou Ben Adhem ” is, that, because he loves his fellow-men, an angel writes his name at the head of the list of those whom “love of God had blessed.” I know not why the names of some of these I speak of should not be written there too, “rough” though they are.

Now that all is over, let me set down, briefly, the light in which the great question lies before me after this experience. I find my face set persistently as ever against the threatening power. Near observation only confirms what we hear of its strength, of its iniquity, of its persistent hostility to what we hold sacred. Of the benefits I have derived from this military experience, it is not the least, that now I know, through my own observation, what before was only hearsay. We have heard that Southern society was ignorant; that, at the South, there was little regard for justice; that the heart of the slaveholder became cruel and hard; that the marriage-tie was held in small respect. We have heard, too, about the effect of slavery upon the negroes; that although it raised them, in a degree, above barbarism,— far enough to make them useful instruments, forcing them into industry and into so much of order and decency as improved them as tools,—yet that there it left them, and interposed iron barriers against their mounting farther in the scale. We have heard, that, under slavery, there can be but one form of industry,— the simplest agriculture; that here the tools are coarse, the methods rude, the operations so carried on as soon to impoverish the earth; that when the surface richness is taken off, instead of replenishing its strength or subsoiling, the soil is simply abandoned, to become a wilderness again, while the planter goes off in search of virgin, inexhausted land.

All these things have been matters of hearsay; but now I can pile fact upon fact, from my own observation, in confirmation. If slavery is to exist, it must extend its area. There are inherent necessities which force it to seek new and again new domain. How lucidly and convincingly is this argued in “The Slave Power”! We must triumph, or, I believe in my heart, we shall see the triumphant South extending its dominion southward and westward into Mexico; thence, in the future, forced by these inherent necessities, into the other continent and the tropical islands, — extending its empire throughout the “golden circle” that surrounds the Gulf of Mexico. This territory, slavery will blast as it has blasted the territory in its possession to-day. It will debase the master-class into the cruelty, the injustice, the corruptness, which we know now as characterizing them. It will maintain the servile class in a situation but little removed from their first barbarism.

I know not how, to-day, any knightly and chivalrous soul can do otherwise than burn to rush forth to prevent this. As I write, the cause of the slave-power languishes. It was otherwise up to the first days of July; or, rather, its decline was less marked than our safety required. I remember well, how in the rifle-pits, toward the end of June, I heard Grosvenor talk, who is now no more. Justice and truth, he held, were in peril as much as when we came forth; and could we go home, and leave it so? Rather ought we to stay, though amid hunger and fever and leaden rain, until light came. Almost in that very hour came the dawning of light. But if skies again darken, if through unforeseen disaster or alien interference the good cause is again imperilled, ought we not to thank God we have learned to endure the march, to poise the rifle, to bear up against the hot, shrill hail of war? So to live, in these times, we feel is to live well; and to die at the front is to die well; and, unto those who die thus, the voice of Christ might say, —

” Come, my beloved! e’en as I was pained,

So art thou broken, and thy life outpoured:

Therefore I bless thee, and give thanks for thee.”