October 2 — This morning we moved to our old camp again, on the Charlestown and Berryville pike, three miles south of Charlestown.

Tuesday, October 2, 2012

October 2d, Thursday.

With what extraordinary care we prepared for our ride yesterday! One would have thought that some great event was about to take place. But in spite of our long toilet, we stood ready equipped almost an hour before Colonel Breaux arrived. I was standing in a novel place — upon the bannisters looking over the fields to see if he was coming —and, not seeing him, made some impatient exclamation, when lo! he appeared before me, having only been concealed by the wood-pile, and O my prophetic soul! Captain Morrison was by his side!

There was quite a cavalcade of us: Mr. Carter and his wife, Mrs. Badger and Mrs. Worley, in two buggies; the three boys, who, of course, followed on horseback, and the two gentlemen, Miriam, Anna, and I, riding also. It was really a very pretty sight, when Captain Morrison and I, who took the lead going, would reach the top of one of the steep hills and look down on the procession in the hollow below. Fortunately it was a very cloudy evening; for, starting at four, it would have been very unpleasant to ride that distance with the sun in our faces.

As we reached the town we heard the loud report of two cannon which caused the elder ladies to halt and suggest the propriety of a return. But if it was a gunboat, that was the very thing I was anxious to see; so we hurried on to the batteries. It proved to be only practicing, however. At the first one we stopped at, the crew of the Arkansas were drilling. After stopping a while there, we followed the river to see the batteries below. It was delightful to ride on the edge of a high bluff with the muddy Mississippi below, until you fancied what would be the probable sensation if the horse should plunge down into the waters; then it ceased to be so pleasant. The great, strong animal I rode could have carried me over without a protest on my part; for the ridiculous bit in his mouth was by no means suited to his strength; and it would require a more powerful arm than mine to supply the deficiency. Miriam had generously sacrificed her own comfort to give him to me; and rode fiery Joe instead of her favorite. But it was by no means a comfort to me. Then Anna was not reconciled to her pony while I was on such a fine horse, until I proposed an exchange, and gladly dismounted near an old mill two miles and a half below Port Hudson, as we returned home.

In leaving the town, we lost sight of the buggies, as there was no carriage road that might follow the bluff; and though there was one just back, we never saw our buggies again. Once, following a crescent, far below us lay the water battery concealed by the trees that grew by the water’s edge, looking, from where we stood, like quite a formidable precipice. Then still beyond, after leaving the river, we passed through a camp where the soldiers divided their attention equally between eating their supper and staring at us in the most profound silence. Then, through an old gate, down a steep hill, past a long line of rifle-pits, a winding road, and another camp where more men stared and cooked their supper, we came to the last battery but one, which lay so far below that it was too late to visit it. We returned highly delighted with what we had seen and our pleasant ride. It was late when we got back, as altogether our ride had been some fifteen miles in length. As soon as we could exchange our habits for our evening dresses, we rejoined our guests at the supper-table, where none of us wanted for an appetite except poor Captain Morrison, who could not be tempted by the dishes we so much relished. After supper, Colonel Breaux and I got into a discussion, rather, he talked, while I listened with eyes and ears, with all my soul. . . . What would I not give for such knowledge! He knows everything, and can express it all in the clearest, purest language, though he says he could not speak a word of English at fourteen!

The discussion commenced by some remark I made about physiognomy; he took it up, and passed on to phrenology — in which he is no great believer. From there he touched on the mind, and I listened, entranced, to him. Presently he asserted that I possessed reasoning faculties, which I fear me I very rudely denied. You see, every moment the painful conviction of my ignorance grew more painful still, until it was most humiliating; and I repelled it rather as a mockery. He described for my benefit the process of reasoning, the art of thinking. I listened more attentively still, resolving to profit by his words. . . . Then he turned the conversation on quite another theme. Health was the subject. He delicately alluded to my fragile appearance, and spoke of the necessity of a strong constitution to sustain a vigorous mind. If the mind prevailed over the weak body, in its turn it became affected by decay, and would eventually lose its powers. It was applicable to all cases; he did not mean that I was sickly, but that my appearance bespoke one who had not been used to the exercise that was most necessary for me. Horseback rides, walks, fresh air were necessary to preserve health. No man had greater disgust for a freckled face than he; but a fair face could be preserved by the most ordinary precautions and even improved by such exercise. He illustrated my case by showing the difference between the flower growing in the sunshine and that growing in a cellar. Father’s own illustration and very words, when he so often tried to impress on me the necessity of gaining a more robust frame than nature had bestowed! And a letter he had made Hal write me, showing the danger of such neglect, rose before me. I forgot Colonel Breaux; I remembered only the ardent desire of those two, who seemed to speak to me through his lips. It produced its effect. I felt the guilt I had incurred by not making greater efforts to gain a more robust frame; and putting on my sunbonnet as I arose from the breakfast-table this morning, I took my seat here on the wide balcony where I have remained seated on the floor ever since, with a chair for a desk, trying to drink an extra amount of fresh air.

I was sorry when Colonel Breaux arose to take his leave. As he took my hand, I said earnestly, “Thank you for giving me something to think about.” He looked gratified, made some pleasant remark, and after talking a while longer, said goodnight again and rode off. While undressing, Miriam and I spoke of nothing else. And when I lay down, and looked in my own heart and saw my shocking ignorance and pitiful inferiority so painfully evident even to my own eyes, I actually cried. Why was I denied the education that would enable me to be the equal of such a man as Colonel Breaux and the others? He says the woman’s mind is the same as the man’s, originally; it is only education that creates the difference. Why was I denied that education? Who is to blame? Have I exerted fully the natural desire To Know that is implanted in all hearts? Have I done myself injustice in my self-taught ignorance, or has injustice been done to me? Where is the fault, I cried. Have I labored to improve the few opportunities thrown in my path, to the best of my ability? “Answer for yourself. With the exception of ten short months at school, where you learned nothing except arithmetic, you have been your own teacher, your own scholar, all your life, after you were taught by mother the elements of reading and writing. Give an account of your charge. What do you know?” Nothing! except that I am a fool! and I buried my face in the sheet; I did not like even the darkness to see me in my humiliation.

October 2, Thursday. Admiral Du Pont arrived to-day; looks hale and hearty. He is a skillful and accomplished officer. Has a fine address, is a courtier with perhaps too much finesse and management, resorts too much to extraneous and subordinate influences to accomplish what he might easily attain directly, and, like many naval officers, is given to cliques, — personal, naval clanship. This evil I have striven to break up, and, with the assistance of Secession, which took off some of the worst cases, have thus far been pretty successful, but there are symptoms of it in the South Atlantic Squadron, though I hope it is not serious. It is well that the officers should not only respect but have an attachment to their commanders, but not with injustice to others, nor at the expense of true patriotism and the service. But all that I have yet seen is, if not exactly what is wished, excusable. Certainly, while he continues to do his duty so well, I shall pass minor errors and sustain Du Pont. He gives me interesting details of incidents connected with the blockade, of the entrance to Stono, and affairs at James Island, where Benham committed a characteristic offense in one direction and Hunter a mistake in another.

Thursday, 2d—We started this morning at 7 o’clock, and reaching Corinth at 10, we marched out two miles west of town where we pitched our tents in the timber for camp. Water is very scarce. I took six canteens and started to find water, but to get it I must have traveled in all four miles. The balance of the day I served on camp guard.

Thursday, 2nd. Renewed our march without breakfast. Scoured the woods for our old friends. Took five men and acted as skirmishers. No bird discovered. Reached camp in the P. M. Heard the boys relate their stories about the fight. Somewhat tired.

Thursday, 2d.—Started to march in direction of Frankfort at 12 M. Camped on Elk Horn Creek, four and one-half miles from Frankfort; stood guard at house until midnight.

On September 17th the fierce battle of Antietam was fought by the Army of the Potomac,—a drawn battle, little better than a defeat for us; and though the rebels retired there was no following up on our part, and no result worth the enormous loss of life.

And now the moment had come for the war-measure Mr. Lincoln had held in reserve. The Government had been fighting to uphold the Government, and announcing all along that if the abolition of slavery proved needful to that end, then slavery should cease.

On September 22, 1862, Mr. Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation declaring that in all States found in rebellion on January 1, slaves should “thenceforth and forever

be free.” Congress, however, delayed to take the action urged upon them by the President, until the time limit expired.

.

Jane Stuart Woolsey to a friend abroad.

Jane Stuart Woolsey to a friend abroad.

8 Brevoort Place, N. Y.

October, 1862.

The fighting at Cedar Mountain and Gainesville and on futile fields of Manassas, the mysterious ups and downs of commanders, the great invasion scare, the mean dissensions and the sad delays, have kept us constantly agitated, the more so that we were in the tauntingly still and sweet country, where the newspaper train was sure to fail in great emergencies. There was a time,—I confess it because it is past, when your correspondent turned rather cold and sick and said “It is enough!” . . . and when my sister Abby, (who acknowledged the Southern Confederacy when the rebel rabble got back unpursued across the river from Winchester), went about declaiming out of Isaiah, ” To what purpose is the multitude of your sacrifices; your country is desolate, strangers devour it in your presence.” . . . We came out of that phase, however, at any rate I did, and concluded that despondency was but a weak sort of treason; and then with the first cool weather came the Proclamation, like a

.

“Loud wind, strong wind, blowing from the mountain,”

.

and we felt a little invigorated and thanked God and took courage. . . . In Litchfield we followed with great interest the growth of the 19th Connecticut recruited in that county, all the little white crumbs of towns dropped in the wrinkles of the hills sending in their twenty, thirty, fifty fighting men; Winsted, Barkhamsted, Plymouth companies, and companies clubbed by the very little villages, marching under our windows every day to the camp ground. Almost all the young men in Litchfield village have gone; the farmers, the clerks in the shops, the singers in the choir. Who is to reap next year’s crops? Who is to sow them? Everyone spoke well of the new recruits. There was not a particle of illusion for them. They understood very well to what they were going; disease, death, a common soldier’s nameless grave. They made themselves a new verse to the marching song:

.

“A little group stands weeping in every cottage door,

But were coming, Father Abraham, three hundred thousand more.”

.

General Tyler went over to Danielsonville to look at a company just raised in that town, and was waited on to know if another company would be accepted. “If it is here this time tomorrow,” he answered in jest. It was there. It is not altogether a question of bounty. A fine young fellow came into our hotel a day or two after the bounty-giving ended, to inquire the way to camp. Charley asked him, “Why didn’t you come before the pay stopped?” “That’s just what I was waiting for,” he answered; and a dozen men went from the village to whom the bounty could offer not the slightest inducement. The Congregational clergyman told us he looked over the growing list of names with tears, knowing what good names they were and how ill they could be spared. But the 19th Connecticut is no better than a hundred other regiments. There are very few men in the 18th Connecticut who are not persons of weight and value in their community, cousin Mary Greene says. And see how they fight! Look at the Michigan Seventh at South Mountain. The Michigan Seventh was two weeks old. And yet it is coming to us from over the sea that we can’t get men, and if we do they will run! . . .

The generalship and fighting of the rebels is also certainly very fine—corn-cobs and no shoes are pathetic when one forgets the infamous cause. . . . Their “obsolete fowling-pieces” go off with considerable accuracy, says a malcontent at my elbow.

When we came to town last week the streets seemed full of anxious and haggard faces of women, and when I caught sight of my own face in a shop glass I thought it looked like all the rest. The times are not exactly sad, but a little oppressive. . . . G. and I cannot stand it any longer and we are off to-morrow. We are in the government service now and entitled to thirteen dollars a month![1] We are going into exile—a blessed exile.

[1] At the Portsmouth Grove Hospital, as assistants to Miss Wormeley.

OCTOBER 2D.—News from the North indicate that in Europe all expectation of a restoration of the Union is at an end; and the probability is that we shall soon be recognized, to be followed, possibly, by intervention. Nevertheless, we must rely upon our own strong arms, and the favor of God. It is said, however, an iron steamer is being openly constructed in the Mersey (Liverpool), for the avowed purpose of opening the blockade of Charleston harbor.

Yesterday in both Houses of Congress resolutions were introduced for the purpose of retaliating upon the North the barbarities contemplated in Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

The Abolitionists of the North want McClellan removed—I hope they may have their will. The reason assigned by his friends for his not advancing farther into Virginia, is that he has not troops enough, and the Secretary of War has them not to send him. I hope this may be so. Still, I think he must fight soon if he remains near Martinsburg.

The yellow fever is worse at Wilmington. I trust it will not make its appearance here.

A resolution was adopted yesterday in the Senate, to the effect that martial law does not apply to civilians. But it has been applied to them here, and both Gen. Winder and his Provost Marshal threatened to apply it to me.

Among the few measures that may be attributed to the present Secretary of War, is the introduction of the telegraph wires into his office. It may possibly be the idea of another; but it is not exactly original; and it has not been productive of good. It has now been in operation several weeks, all the way to Warrenton; and yet a few days ago the enemy’s cavalry found that section of country undefended, and took Warrenton itself, capturing in that vicinity some 2000 wounded Confederates, in spite of the Secretary’s expensive vigilance. Could a Yankee have been the inventor of the Secretary’s plaything? One amused himself telegraphing the Secretary from Warrenton, that all was quiet there; and that the Yankees had not made their appearance in that neighborhood, as had been rumored! If we had imbeciles in the field, our subjugation would be only pastime for the enemy. It is well, perhaps, that Gen. Lee has razed the department down to a second-class bureau, of which the President himself is the chief.

I see by a correspondence of the British diplomatic agents, that their government have decided no reclamation can be made on us for burning cotton and tobacco belonging to British subjects, where there is danger that they may fall into the hands of the enemy. Thus the British government do not even claim to have their subjects in the South favored above the Southern people. But Mr. Benjamin is more liberal, and he directed the Provost Marshal to save the tobacco bought on foreign account. So far, however, the grand speculation has failed.

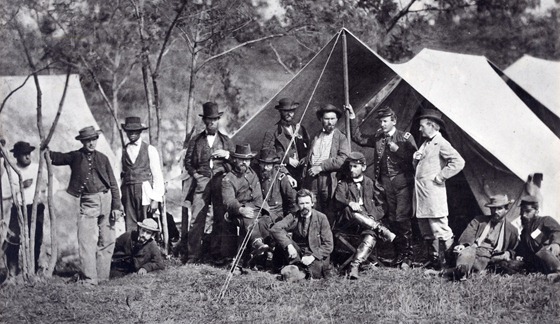

Incidents of the war, group at Secret Service Department Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, Antietam, October 1862.

50th year anniversary print (1912) from original print.

Summary: Photograph shows fourteen men, including Allan and William Pinkerton, and several Union Army officers posed in front of a tent.

Library of Congress image.

October 2.—We are very busy, trying to get clothes made for the exchanged prisoners. They are in a dreadful state for want of them; many of them have not changed their clothes for more than a mouth. Some of the ladies of the place promised to help us, but we have as yet seen nothing of them; they do not assist us in any way. This is not a wealthy place, and our army has been here for some time, which has impoverished it still more.

The prisoners complain bitterly of their treatment while in Jackson, Miss. Some of them told me that if they had been convicts they could not have been worse treated. This is something I can not understand. Who could forget Fort Donelson, and the hardships our poor men endured there! Every time I think of it a cold shudder runs through me; and then, to think what these poor fellows have endured since, during nearly one long year, in a cold northern prison! I hope that the patriotic state of Mississippi “has not tired of well-doing.”