Chickasaw, Ala., Thursday, Oct. 29. We were called up long before daylight, the stars brightly shining, and all was indicative of an early move, camp fires blazing brightly in all directions, baggage wagons a-moving and orderlies flying back and forth, but our place was in the rear to-day, so we took our time. Piled all the corn my horses could eat before them, cleaned them, then shelled my nose-bags full for the march. By that time—had a splendid breakfast ready of fresh meat, sweet potatoes and fried crackers. Harnessed and hitched up by seven was on the road by 7 A. M., but as the Division train was to go ahead of us, we were delayed considerable before we got under way. Frequent and heavy booms of cannonading could be plainly heard to the east, with a distant roll of musketry, and: we knew not but we were going into a fight. But we took a road leading directly north, crossing the railroad. We marched slow, frequent halts in the fore part of the day. Our course was northwest through poor country, hilly, timbered with scrub oak and pine, the road crooked and very stony. Passed but few houses and these of the poor rickety-log kind such as a well to do farmer would not put his horse in. Clearings small, filled with stones and stumps, but generally very good corn growing, and occasionally a patch of sweet potatoes which suffered from the hands of thoughtless soldiers; but I could not think of laying hands on the small stock of the poor half-clad old women and children we saw. Halted at noon and fed, putting on our nose-bags without unhitching. The water along the road was beautiful pearly springs and pebbly brooks on every side, which was enticing to look at. (Who would ask for better beverage than this?) Reached Chickasaw—a small deserted place on the Tennessee River, by 5 P. M.; found the other brigades here. The advance arrived a little after noon, but have not yet unharnessed as they expect to cross the river. We unharnessed and fed. Stuck up our tents as it looked like rain, but we were told we would have to cross to-night. A mile below is Eastport, Miss., where a good boat is busy at work crossing over the 4th Division. Health and spirit good, but would like to get mail.

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Colonel Lyons.

Nashville, Tenn., Oct. 29, 1863.—We are encamped in a dry, beautiful location in Edgefield, directly across the river from Nashville and about one-half mile from the railroad bridge. Edgefield is a clean, quiet village, and we have decidedly the softest thing that we have had since I have been with the regiment. We shall probably remain here some time, perhaps all winter, unless some unexpected emergency arises at the front.

Now make all your arrangements to come to me, and I will make my arrangements for you as fast as I can. I am living in a tent now, but will find a house, or some rooms, as soon as I can. It is necessary for you to have a permit to come here. I will have no difficulty in getting it, I think, and will send it to you in a few days, together with a list of articles you will need to bring with you.

The regiment is furnishing guards in the city, about 150 per day, which is our only duty. The weather is most lovely, and it is a delightful change from the rain and mud and filth of Stevenson.

A torpedo was exploded under one of the trains that had our regiment, when coming here, which threw the engine off the track and made a perfect wreck of the tender, but fortunately no one was hurt. This occurred Sunday night, about 28 miles this side of Stevenson.

Thursday, 29th—I went down to our old stamping ground to-day. I stopped to see Miss Eugenie Holt; had just returned from a visit to Marietta and was looking very pretty; stopped but a short time. Went on to Mr. Davis’s; nobody at home but Miss Mollie. Crossed the River at Freeman’s Ferry and went to Mr. Somers. Miss Maggie’s husband at home. I staid all night. Miss Mattie came down this morning. I staid till bout 10 o’clock.

Lenoir, October 29th.

Another letter from home last night, dated October 1 6th. Only four letters in two months; I find, too, my letters are quite as irregular.

I have just learned that Lieutenant Miller starts for home at 6 o’clock tomorrow morning. He will visit my loved ones and tell them all the news. I know not how to express myself in regard to our present situation. I am glad we were not forced to retreat. Still, I am certain we could have held those heights, and to leave without firing a gun! Oh, for a few Wolfords and Grants—men who are “here to fight.”

All sorts of rumors are afloat. “Bragg, with all his army, is advancing.” Longstreet is crossing the river six miles below Kingston to flank us on the right. Another heavy force is on our left, making for Knoxville. “Wilcox has been driven back from the east,” and a hundred others equally encouraging. We know not what to think of it, and yet must criticise and form conclusions. But it is all explained at last. We fell in at 1 o’clock today, marched about a mile to a beautiful grove near a large spring of never-failing water. Here our division formed in line and stacked arms, with orders to remain in line until further notice. Lieutenant Colonel Comstock soon called our regiment to “attention,” ordered company commanders in front of center, and then and there revealed to them the long-wished-for intelligence. All officers and men were taken by surprise. We were prepared to hear of some great calamity, but not for this. Nothing like it had ever before happened to the Ninth Army Corps. “Our fall campaign is closed. Prepare for yourselves comfortable quarters for the winter.” For a moment there was a silence that could be felt, then a shout went up that “rent the heavens and shook the everlasting hills.” Not simply because we were ordered to prepare winter quarters, but a mysterious movement had been explained—a weight of anxiety removed.

29th. Boys went out for forage, every man for himself, horses having stood hungry all night. Lay and slept considerably during the forenoon. Boys got some apples. Saw the boys play poker some. Am glad I have not the habit of playing. Col. sent for wagons to come up. Mail sent for. Bosworth went. Getting uneasy.

Thursday, 29th—It is quite pleasant today. The Mississippi river is slowly rising. Produce is very high here at Vicksburg and fruit and vegetables are scarce this fall because of the large armies in and around this section for more than a year. What little stuff has been grown by the farmers was confiscated by the soldiers before it was matured, so what we get is shipped down from the North, and we have to pay about four prices for it. Potatoes and onions are $4.00 a bushel, cheese (with worms) is fifty cents per pound, and butter—true, it’s only forty cents a pound, but you can tell the article in camp twenty rods away. Vicksburg being under military rule makes it difficult for the few citizens to get supplies, which they can obtain only from the small traders who continued in business after the surrender, or from the army sutlers. No farmers are allowed to come in through the lines without passes, and even then no farmer, unless he lives a long distance from Vicksburg, has anything to bring in.

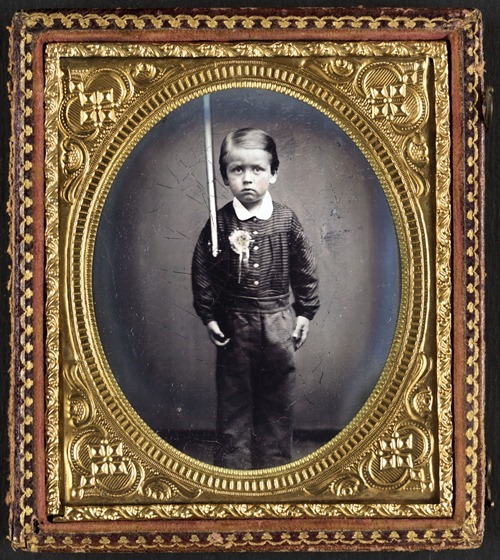

Unidentified young boy wearing secession badge and holding a rifle

__________

Sixth-plate ambrotype, hand colored ; 9.4 x 8.2 cm (case)

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot and/or scratch removal

- cropped for composition and/or to accentuate subject matter

- straighten image

Civil War Portrait 077

by John Beauchamp Jones

OCTOBER 29TH.—Gen. Lee writes (a few days since), from Brandy Station, that Meade seems determined to advance again ; that troops are going up the Potomac to Washington, and that volunteers from New York have been ordered thither. He asks the Secretary to ascertain if there be really any Federal force in the York River; for if the report be correct of hostile troops being there, it may be the enemy’s intention to make another raid on the railroad. The general says we have troops enough in Southwestern Virginia; but they are not skillfully commanded.

After all, I fear we shall not get the iron from the Aquia Creek Railroad. In the summer the government was too slow, and now it is probably too slow again, as the enemy are said to be landing there. It might have been removed long ago, if we had had a faster Secretary.

Major S. Hart, San Antonio, Texas, writes that the 10,000 (the number altered again) superior rifles captured by the French off the Rio Grande last summer, were about to fall into the hands of United States cruisers ; and he has sent for them, hoping the French will turn them over to us.

Gen. Winder writes the Secretary that the Commissary-General will let him have no meat for the 13,000 prisoners; and he will not be answerable for their safe keeping without it. The Quartermaster-General writes that the duty of providing for them is in dispute between the two bureaus, and he wants the Secretary to decide between them. If the Secretary should be very slow, the prisoners will suffer.

Yesterday a set (six) of cups and saucers, white, and not china, sold at auction for $50.

Mr. Henry, Senator from Tennessee, writes the Secretary that if Ewell were sent into East Tennessee with a corps, and Gen. Johnston were to penetrate into Middle Tennessee, forming a junction north of Chattanooga, it would end the war in three months.

October 29.—Major-General George H. Thomas sent the following dispatch to the headquarters of the United States army, from his camp at Chattanooga, Tenn.:

“In the fight last night the enemy attacked General Geary’s division, posted at Wauhatchie, on three different sides, and broke into his camp at one point, but was driven back in most gallant style by a part of his force, the remainder being held in reserve. General Howard, whilst marching to Geary’s relief, was attacked in flank. The enemy occupying in force two commanding hills on the left of the road, he immediately threw forward two of his regiments and took both of them at the point of the bayonet, driving the enemy from his breastworks and across Lookout Creek. In this brilliant success over their old adversary, the conduct of the officers and men of the Eleventh and Twelfth corps is entitled to the highest praise.”—(Doc. 211.)

—The flag of truce boat arrived at Annapolis, Md., from City Point, Va., with one hundred and eighty-one paroled men, eight having died on the passage from actual starvation. A correspondent says:

“Never, in the whole course of my life, have I ever seen such a scene as these men presented; they were living skeletons; every man of them had to be sent to the hospitals, and the surgeon’s opinion is, that more than one third of them must die, being beyond the reach of nourishment or medicine.

“I questioned several of them, and all state that their condition has been brought on by the treatment they have received at the hands of the rebels. They have been kept without food, and exposed a large portion of the time without shelter of any kind. To look at these men, and hear their tales of woe and how they have been treated, one would not suppose they had fallen into the hands of the Southern chivalry, but rather into the hands of savage barbarians, destitute of all humanity or feeling. If human means cannot be brought to punish such treatment to prisoners, God, in his justice, will launch his judgments upon the heads of any people who will so far forget the treatment due to humanity.

“It seems to be the policy of the South to keep the Union prisoners until they are so far worn out as ever to be unfit for service again, and then send them off to die; while the men captured by the Nationals are returned to them well clothed and well fed, ready to go into the field the moment they arrive within their lines.”

—Jefferson Davis sent the following letter to Lieutenant-General Polk, who had been relieved of his command, upon a charge of mismanagement at the battle of Chickamauga:

“After an examination into the causes and circumstances attending your being relieved from command with the army commanded by General Bragg, I have arrived at the conclusion that there is nothing to justify a court-martial or court of inquiry, and I therefore dismiss the application.

“Your appointment to a new field of duty, alike important and difficult, is the best evidence of my appreciation of your past services and expectation of your future career.”