Monday, 26th—Wednesday, 28th—-Nothing worthy of note.

October 2013

Lenoir, Tenn., October 28th, 1863.

I said yesterday that I was puzzled. I am more than ever today. I am confounded, disappointed, chagrined.

Our forces evacuated Loudon early this morning. The Rebels took immediate possession. Everything of value that could not be removed was destroyed. Only last night a locomotive was run across the river to be used on that side as we advanced. Four cars had been left there by the Rebels when they evacuated. As we had no time to remove them, the engineer put on steam and ran them off the embankment into the river. The Union people left with us. We have fallen back six miles and encamped for the night. A strong force is posted on the heights to prevent surprise.

I am simply stating facts as they occur. Of course, I cannot know the whys and wherefores of these movements. Perhaps they are part of the “original plan,” and not a retreat. We all have confidence in Burnside, but, if we do not see Knoxville between now and Sunday I am much mistaken. To my heated imagination the Cumberland Mountains loom up with wonderful distinctness.

28th. At 2:30 relieved and ordered to Jonesboro, 11 miles. Cold ride. Reached there at sunrise, reported to Shackleford. Sent on G. road half a mile, dismounted and fed. Whole army retreating. Went mile east of town where Regt. in line. Stayed and waited for Capt. Case to come from the river. Got chestnuts. Sent for provisions. Fed below Leesburg, then marched to old camp at Henderson Station.

October 28 — We moved camp to-day, and are now about one mile west of Brandy Station, and not far from the residence of John Minor Botts. His house is situated about a mile and a half nearly west of Brandy Station and about half a mile from the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. It is located on a beautiful eminence which slopes gently down to a level plain that lies in front of the house and extends to the railroad. The house is large and plain, nearly square, built of wood and painted white; it faces toward sunrise and the railroad, and it has a large and stately portico in front. John Minor Botts is an eminent lawyer and politician, and a strong and pronounced Union man.

Wednesday, 28th—The weather is getting quite cool, particularly the nights, and a little fire in our tents in the evening makes it quite comfortable and homelike. It is different on picket, where no fires are allowed, except on the reserves’ posts. Troops are leaving Vicksburg nearly every day, going to northern Mississippi and western Tennessee to occupy garrisons made vacant by General Sherman’s men going to the relief of the army cooped up in Chattanooga.

28th.—Our niece, M. P., came for me to go with her on a shopping expedition. It makes me sad to find our money depreciating so much, except that I know it was worse during the old Revolution. A merino dress cost $150, long cloth $5.50 per yard, fine cotton stockings $6 per pair; handkerchiefs, for which we gave fifty cents before the war, are now $5. There seems no scarcity of dry-goods of the ordinary kinds; bombazines, silks, etc., are scarce and very high; carpets are not to be found—they are too large to run the blockade from Baltimore, from which city many of our goods come.

Washington, D. C,

Oct. 28, 1863.

Dear Sister L.:—

I have just time to tell you the result of my examination, which came off yesterday. Just as I expected, the result depended on the surgeon’s verdict. Before the board I passed without trouble, unless study be trouble, and I hope I satisfied the doctor that I could see a commission. It tried my eyes to do it, though, I assure you of that.

I tried this morning to find out my fate. I could not satisfy myself, but those who pretend to know the ropes and who have heretofore been correct, say I am booked for straps, “First Lieutenant—First Class.” If so I am content. It was what I worked for. Many of my comrades here express surprise that it was not a captaincy. I am not surprised, and should not have been if it had been second lieutenant. It is no boy’s play to satisfy that board that you can make even a lieutenant.

However, it may be all moonshine and perhaps I am rejected after all, but if I am, the surgeon did it.

I return to the army to-morrow, and in the course of a week or two I shall be officially notified of the result, when I will lose no time in informing you. I hope to be able, if successful, to get leave of absence for a few days to come and see you. You would be glad to see me, wouldn’t you? My letters from the army haven’t been sent up. No doubt there is one or more there from you. If there is not I shall think you don’t care much about me, anyway, and shall not care to come home.

374 North Capitol Street,

Washington, D. C, Oct. 28, 1863.

Dear Father:—

The great day for me was yesterday. After waiting almost a month the door swung on its hinges to admit Private O. W. N. to the presence of the arbiters of his fate who would transform him to a “straps” or send him back to his regiment to be the butt for the ridicule of his companions.

Well, it is all over with and I breathe freer. My examination occupied forty-five minutes, and in that time I missed only two questions, and those on points which I had stated to the board that I was not prepared to answer. My examination was unusually long. Many have been commissioned on a ten or fifteen minutes’ examination and very few privates or non-commissioned officers stay in over half an hour.

I was the last one examined, and after I left the room to be examined by the surgeon, a sergeant heard the general remark that they had “not had to reject a man to-day.” So I am satisfied that I am all right if the surgeon was satisfied with me. In testing my eyes he sent me to the corner of the room and the clerk covered one of my eyes at a time while the doctor held up something and asked me what it was. I had played sharp on him by taking an inventory of the articles on the table. I could see just enough with one eye to tell a pen from a paper knife, and a pair of scissors from a cork. He discovered that I was a little near-sighted. He asked me if I could march twenty-five miles and not be sick. That was a thrust at my “shanghais,” but I told him with emphasis I could and had, and he seemed satisfied. He wouldn’t look at my captain’s letter, probably thought he didn’t want any assistance in determining my physical ability.

I went down this morning to try to learn the result, but I could not.

October 28—On my way to the wards this morning I was annoyed at something which happened. I had made up my mind to leave the hospital, but on entering the wards all of this feeling vanished. When I saw the smile with which I was greeted on every side, and the poor sufferers so glad to see me, I made up my mind, I hope for the last time, that, happen what may, nothing will ever make me leave the hospital as long as I can be of any service to the suffering.

The surgeons have told me it is impossible for Mr. Groover to live. I have written to his wife, and told her of his condition. Poor man! he cried like a child when spoken to about his wife, and begged me not to let her know how badly he was wounded.

We have a badly wounded man, named Robbins; he has always a smile on his face and a joke for every one. He sings hymns all the time, and I am told on the battle-field he was as cheerful as he is now.

We have two lads severely wounded; one named Moore, from North Carolina, wounded in the lungs. He is as patient as if he were an old man. The other, named Seborn Horton, from Alabama; ho is not more than sixteen years of age. He is a great sufferer. Nothing pleases him better than to have ladies come to see him, and I beg all the girls, little and big, to come. One day I took some ladies to see him, and there was a crowd of little girls standing around him. I remarked that he would be pleased now. He answered that he was, but he was afraid the girls would not come back again. They had brought him a bouquet, which he prized very highly. Our men all seem fond of flowers.

We have numbers of Texas soldiers, members of Hood’s division. They are a fine-looking lot of men, and seem brave enough to face any danger. I have had not a little quarreling with them. They will have it that this army is not to be compared with the one in Virginia for bravery. I do not agree with them, for I have always heard it said that up here we have the flower of the North with which to contend. But these things do for something to talk about. It is amusing to hear the men abusing the different states. Of course it is all in jest, but sometimes they wax quite warm on the subject.

When our army was in Mississippi, had I believed one half the stories told of the people, I should have thought it the meanest state in the Confederacy.

While in Tennessee the same story was told; and now that we are in Georgia, it is honored by the same cognomen. I have come to the conclusion that where our army is that by it the country is injured, and that makes the people do things they otherwise would not. This the soldiers do not think about.

It is reported that General Thomas has superseded General Rosecrans, and that at Chattanooga we have the enemy completely hemmed in.

Our army is on Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain, and we have possession of the Nashville Railroad. The enemy have to haul their supplies from a great distance. On this account it is rumored that they are starving in Chattanooga. But I have heard some say that, with all their drawbacks, they are not only not starving, but are being heavily reinforced. It seems like folly to listen to any thing. I hope and pray that General B. will not feel too secure, and that he will be on the alert. Nearly all the defeats we have ever had have been from our want of caution.

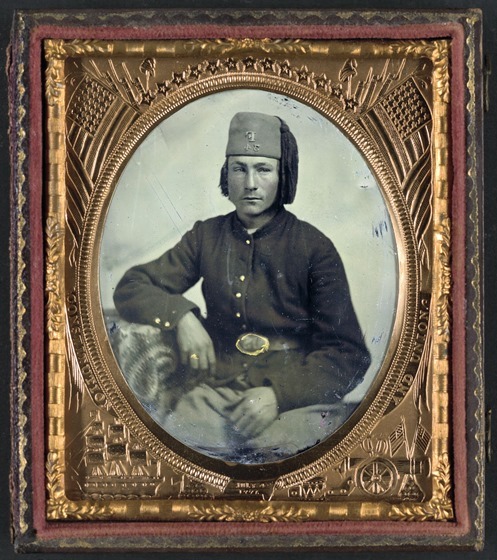

Unidentified soldier of Company F, 34th Ohio Infantry Regiment or Piatt’s Zouaves.

Note: As with many ambrotypes and tintypes, the image is a reverse image.

__________

Sixth-plate tintype, hand-colored ; 9.3 x 8.0 cm (case)

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot and/or scratch removal

- cropped for composition and/or to accentuate subject matter

- straighten image

Civil War Portrait 076