Gilbertsboro, Ala., Thursday, Nov. 5. Thanks to the corporal of the guard we did not get up till nearly 4 A. M. this morning, as he slept and did not wake the orderly at the proper time. But we had to hurry up to start at 5 A. M. which was a good while before daylight. Left the 3rd Brigade behind. They were just having reveille. A cloudy morning. Marched six miles through a flat country heavily timbered, with excellent soil, but entirely uncultivated. It lies in the hands of speculators. When we neared Sugar Creek it became bluffy and rocky, which was all fenced and cultivated by poor folks. Came up to the 2nd Brigade here and we halted three hours to allow them to get out of the way. We went to a neighboring corn crib, and shelled nose bags full of corn. Commenced raining very heavily. At 1 P M. we hitched and started out. The rain fell in torrents but the boys were as merry as ever and forgot the wet in singing. Halting, the infantry built a bridge across the stream with rails. Marched very lively over a hilly road but rich valley. The clay, which in dry weather made good roads, was soon converted into bottomless mud. Came into camp at sundown at Gilbertsboro, Limestone County, Alabama. A very rich plantation here surrounded by very high hills. A large amount of fodder and hay was stored away in the surrounding houses which were soon emptied by the boys and fed to the horses or made for beds. Hungarian grass and millet was the most of it. Division commissary issued out plenty of fresh meat for the boys and there was not much shooting. This evening thirty barrels of whiskey was found buried by the 48th Indiana close to camp, so there were several drunken men in camp.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

Colonel Lyons.

Nashville, Tenn., Nov. 5, 1863.—I am on a court of inquiry, to investigate a matter connected with the shooting and killing of one of his men by Colonel Meisner, of the 14th Mich., and shall be so occupied all of this week. We hold one session per day at the capitol, from 9 a. m. until noon. At the election last Tuesday, the 13th gave 400 majority for the Union ticket, only 18 or 20 votes cast for Palmer. I see by yesterday’s papers that the State has gone Union by a large majority.

I am on the track of a house two blocks from camp, which I think I can get. Boats are running up the river quite freely now, and occasionally get fired into between here and Clarksville. That region is full of guerillas now, since the troops are withdrawn from Donelson and Clarksville. The 83d is there yet, but can not do much for want of numbers.

Captain Hewitt and I have rented a house together and I moved into it on Tuesday. It is a brick house, two rooms, one story, in a quiet, pleasant spot, about 30 rods from the camp. We pay ten dollars per month rent. I send you a diagram. Mrs. Hewitt and you had better come on together. We shall have to mess together. The rooms are large and commodious, good walls and floors, and excellent fireplaces, don’t smoke a particle. We will live in our room and eat in their room. Jerry and Minerva have an outside room, and have in it a little stove that I had for my tent.

November 5th.—For a week we have had such a tranquil, happy time here. Both my husband and Johnny are here still. James Chesnut spent his time sauntering around with his father, or stretched on the rug before my fire reading Vanity Fair and Pendennis. By good luck he had not read them before. We have kept Esmond for the last. He owns that he is having a good time. Johnny is happy, too. He does not care for books. He will read a novel now and then, if the girls continue to talk of it before him. Nothing else whatever in the way of literature does he touch. He comes pulling his long blond mustache irresolutely as if he hoped to be advised not to read it—”Aunt Mary, shall I like this thing?” I do not think he has an idea what we are fighting about, and he does not want to know. He says, “My company,” “My men,” with a pride, a faith, and an affection which are sublime. He came into his inheritance at twenty-one (just as the war began), and it was a goodly one, fine old houses and an estate to match.

Yesterday, Johnny went to his plantation for the first time since the war began. John Witherspoon went with him, and reports in this way: ”How do you do, Marster! How you come on?”—thus from every side rang the noisiest welcome from the darkies. Johnny was silently shaking black hands right and left as he rode into the crowd.

As the noise subsided, to the overseer he said: “Send down more corn and fodder for my horses.” And to the driver, “Have you any peas?” “Plenty, sir.” “Send a wagon-load down for the cows at Bloomsbury while I stay there. They have not milk and butter enough there for me. Any eggs? Send down all you can collect. How about my turkeys and ducks? Send them down two at a time. How about the mutton? Fat? That’s good; send down two a week.”

As they rode home, John Witherspoon remarked, “I was surprised that you did not go into the fields to see your crops.” “What was the use?” “And the negroes; you had so little talk with them.”

”No use to talk to them before the overseer. They are coming down to Bloomsbury, day and night, by platoons and they talk me dead. Besides, William and Parish go up there every night, and God knows they tell me enough plantation scandal—overseer feathering his nest; negroes ditto at my expense. Between the two fires I mean to get something to eat while I am here.”

For him we got up a charming picnic at Mulberry. Everything was propitious—the most perfect of days and the old place in great beauty. Those large rooms were delightful for dancing; we had as good a dinner as mortal appetite could crave; the best fish, fowl, and game; wine from a cellar that can not be excelled. In spite of blockade Mulberry does the honors nobly yet. Mrs. Edward Stockton drove down with me. She helped me with her taste and tact in arranging things. We had no trouble, however. All of the old servants who have not been moved to Bloomsbury scented the prey from afar, and they literally flocked in and made themselves useful.

5th. Up at 4 A. M. Co. “C” ordered to go with Capt. Easton on scout. Got on wrong road, being dark. Trotted two or three miles, returned and fell in with the regt. Moved to near Rheatown and waited for 5th Ind. to come down from Leesburg. Rainy and unpleasant. 14th Ill. to front. Returned near old camp. During night rained heavily. Boys got very wet. Slept well and dry.

Thursday, 5th—It rained all day and on account of it the fatigue party did not work on the fortifications. Our camp number 3 is located on the town commons, and because of no timber near by the northwest wind has a full sweep over the camp. No news of importance.

November 5 — We had a grand review to-day. General Stuart’s cavalry corps and horse artillery passed in general review before General R. E. Lee and John Letcher, Governor of Virginia. We arrived on the field early in the day. A great many of the cavalry were then already arriving on the review ground from two or three different directions, and the whole field was soon covered with bodies of horsemen in their cleanest attire and best appearance, all carefully prepared and trying to look pretty for review. Some of us men tried to blacken our shoes by rubbing them over a camp kettle.

On the east side of the field on a small wave-like hill was a flagstaff with a large, new, beautiful Confederate flag proudly floating in the crisp November breeze. At twelve o’clock the troops were all formed and ready for the grand reviewing exhibition. General R. E. Lee and staff, General Stuart and staff, and Governor Letcher rode in a gentle gallop along the whole length of the line, then quickly repaired to the review station and assembled in the rippling shadow of the large Confederate flag that moved above their heads.

When the resplendent and brilliant little cavalcade, with the grand old chieftain, R. E. Lee, in the center, had settled down for business, the column of horsemen began to move like some huge war machine. The horse artillery moved in front, then came the cavalry in solid ranks and moving in splendid order,— horsemen that have followed the feather of Stuart in a hundred fights. General Wade Hampton’s mounted band was on the field and enlivened the magnificent display with inspiring strains of martial music. The review was held on John Minor Botts’ farm. After the review we came back to camp, when the first section of our battery was detached from the battalion and ordered to report to our old brigade, now commanded by General Rosser.

We immediately prepared to march after we received the order, and at dusk we left the battalion camp and started for Rosser’s brigade. At ten o’clock to-night we arrived at Rosser’s camp near Major’s house on the Rickseyville road, about eight miles north of Culpeper Court House. We had very dark and difficult marching to-night on a cut across the country road; at one place one of our horses fell in a ditch, which detained us some little time to extricate it from its doubled-up, hors de ditch situation.

November 5, 1863. — A warm fall evening. How I am moved as I read the letter below. My own dear boys, and my feelings towards the soldiers who are kind to them; Willie too — the name of sister Fanny’s lost boy. Oh, and my dear sister too. How many will love General Sherman for that letter who would never care for any laurels he might earn in battle.

[Pasted in the Diary is a copy of General Sherman’s famous letter to Captain C. C. Smith of the Thirteenth Regulars, thanking the regiment — in which his little son Willie had fancied himself a sergeant — for the “kind behavior” of its officers and soldiers to his “poor child.” “Please convey to the battalion,” the letter says in conclusion, “my heartfelt thanks, and assure each and all that if in after years they call on me or mine, and mention that they were of the Thirteenth Regulars, when poor Willy was a sergeant, they will have a key to the affections of my family that will open all it has, that we will share with them our last blanket, our last crust.”]

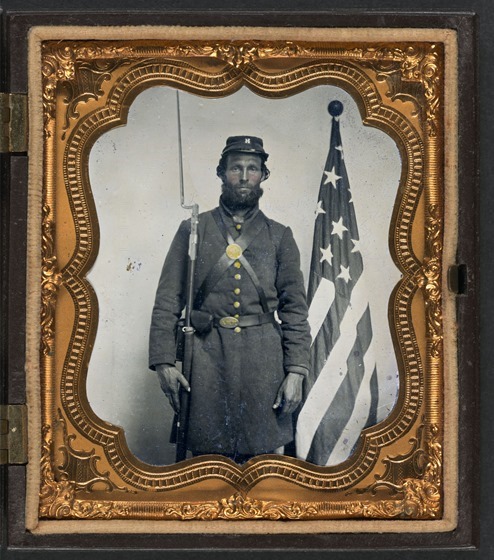

Unidentified soldier in Union uniform and Company H cap with bayoneted musket, cap box, and Volunteer Maine Militia (VMM) belt buckle in front of American flag

__________

Sixth-plate tintype, hand-colored ; 9.5 x 8.4 cm (case)

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:

- fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot and/or scratch removal

- cropped for composition and/or to accentuate subject matter

- straighten image

Civil War Portrait 084

by John Beauchamp Jones

NOVEMBER 5TH.—The President has not yet returned, but was inspecting the defenses of Charleston. The Legislature has adjourned without fixing a maximum of prices. Every night troops from Lee’s army are passing through the city. Probably they have been ordered to Bragg.

Yesterday flour sold at auction at $100 per barrel; to-day it sells for $120! There are 40,000 bushels of sweet potatoes, taken by the government as tithes, rotting at the depots between Richmond and Wilmington. If the government would wake up, and have them brought hither and sold, the people would be relieved, and flour and meal would decline in price. But a lethargy has seized upon the government, and no one may foretell the consequences of official supineness.

The enemy at Chattanooga have got an advantageous position on Bragg’s left, and there is much apprehension that our army will lose the ground gained by the late victory.

The Commissary-General (Northrop) has sent in his estimate for the ensuing year, $210,000,000, of which $50,000,000 is for sugar, exclusively for the hospitals. It no longer forms part of the rations. He estimates for 400,000 men, and takes no account of the tithes, or tax in kind, nor is it apparent that he estimates for the army beyond the Mississippi.

A communication was received to-day from Gen. Meredith, the Federal Commissioner of Exchange, inclosing a letter from Gov. Todd and Gen. Mason, as well as copies of letters from some of Morgan’s officers, stating that the heads of Morgan and his men are not shaved, and that they are well fed and comfortable.

November 5.—The United States transport Fulton captured the rebel blockade steamer Margaret and Jessie, this morning, at seven o’clock, when off Wilmington, N. C. The look-out at the foretop masthead made out a suspicious steamer painted entirely white, and burning soft coal, three points on the port-bow ; immediately gave chase, which resulted in her altering her course several times; following her, after a short time it was discovered that she was throwing cargo overboard, which confirmed our first suspicions that she was a blockade-runner. There was also in sight a fore-and-aft-rigged gunboat, five points on our port-bow. She remained in sight for a short time, when we lost sight of her astern. At ten A.M., made a side-wheel gunboat on the port-beam, (afterward ascertained to be the Keystone State.) About this time we fired three shots at the chase from a twenty-pound Parrott gun, falling short of the mark. At eleven A.M., made a side-wheel gunboat, (afterward ascertained to be the Nansemond,) three points on the port bow, also in pursuit. From this time until four P.M., continued in pursuit, gradually widening the space between us and the gunboats, and nearing the chase, when, after having fired fifteen shots, some of which passed entirely over the object, and others striking quite near, and after leaving our competitors far astern, the prize hove to. At this time the Keystone State was about ten miles astern, and the Nansemond about five miles. When the prize hove to, a prize crew, in charge of our first officer and the purser, was immediately sent on board, and a hawser from our stern attached to the prize— now ascertained to be the steamer Margaret and Jessie, of Charleston, from Nassau, N. P., for a confederate port The gunboat Nansemond arrived alongside the prize about half an hour, and the Keystone State about one hour after our hawser was made fast to the prize. This steamer is a valuable vessel, of about eight hundred tons burden, and has on board an unusually valuable cargo.—Official Report.

—The bombardment of Fort Sumter was kept up by slow firing from the monitors and land batteries.

—General Sanders, in command of a Union cavalry force, overtook a rebel regiment at Motley’s Ford, on the Little Tennessee River, charged and drove them across the river, capturing forty, including four commissioned officers. Between forty and fifty were killed or drowned, and the entire regiment lost their arms. Colonel Adams, who led the charge, lost no man or material.— Tbe ship Amanda was captured and burned, when about two hundred miles from Java Head,

by the confederate steamer Alabama.—Brownsville, Texas, was occupied by the National troops, under the command of Major-General Banks, the rebels having evacuated the place, after destroying the barracks and other buildings.—(Doc. 6.)