Saturday, 14th—Left Mr. Hatcher’s and came up to Cave Spring, saw Jenkins and Capt. Hooks. Mart Lee was there but I did not get to see him. Came on to Dr. Richardson’s near Cedar Town and staid all night, a very fine family indeed. Has one grown daughter. Met Col. Bryant, a Kentucky refugee.

Thursday, November 14, 2013

Lenoir, Tenn., November 14th, 1863.

We have been under orders for several days to be ready to fall in at a minute’s notice. That order was repeated at 3 o’clock this morning. We had become so accustomed to it, we began to think it only form, and meant nothing. At sunrise, however, we were startled by the order, “Pack everything and be ready to march immediately, bag and baggage.” Officers’ baggage was put on wagons, the sick in ambulances, supplies of food and clothing—a fresh supply had but just arrived—were reloaded, and the whole train headed toward Knoxville.

Our consternation can better be imagined than described. Every movement spoke of evacuation; of hasty, inglorious retreat. About 10 o’clock the cars came screaming in from Knoxville, bringing General Bumside. The wagon train was nearly formed, and, in half an hour, everything would have been ready for a general stampede. At 10 o’clock the bugle sounded fall in, and off we started toward Loudon. It soon leaked out the Rebels are crossing six miles below Loudon, and Burnside’s arrival had changed the program. So away we went, through rain and mud, fourteen miles without stopping to rest, rejoicing it was not, after all, an ignominous retreat. We halted a little after dark in a thick wood, with orders to light no fires, but remain beside our arms, ready to fall in when called on. It had been very warm during the day, raining at times, and those not wet with rain were wet with sweat. Toward night the wind had changed, and it was bitter cold. And there we sat, two hours or more, cold and hungry, having eaten nothing since morning. The men began to grow impatient. The First Brigade were on our left, and fires burned brightly all along their line. Why could not we have fires? Tom Epley, of our company, thought we could, and away he goes for a coal of fire, while others gather wood and kindlings. But our lynx-eyed Adjutant discovers it, and down he comes. “Who built that fire?” says he. “I did, sir,” says Tom. “Didn’t you know ’twas against orders?” “No, sir; I thought the order was one fire to a company, sir.” “You must put it out.”

“Then how the h—1 are we to cook? Do you think we can march all day in rain and mud and eat flour and raw beef?” “It’s tough, boys,” says the Adjutant, “but that’s the order.” Tom did not put out the fire, but built it larger, and soon the order came, “One fire to a company.”

We kept our fires brightly burning all night, expecting each moment the coming order. At 4 o’clock it came. Fall in, boys, very quietly, and quick as possible. Then, “about face,” and off we went in the darkness, taking precisely the route we came. What was the meaning of this backward move? Our officers agreed it was to draw them out from the river that we might cut off their retreat and “bag them,” as is our custom. We marched slowly and reached Lenoir about 2 p. m., when we formed in line of battle. At dark the Eighth Michigan was thrown out as skirmishers, or outpost pickets. They advanced about four miles on the Jamestown road, and as they formed their last post were fired on by Rebel pickets. The Rebels then rallied their skirmishers and charged the Eighth, which fell back to within a mile of our line of battle. They then faced about, charged the advancing Rebels, drove them a short distance, and held them until relieved. I now began to see how matters stood. The enemy had pursued us promptly and with energy; we were in line of battle awaiting an attack. Would they attack us before daylight? Probably not, as we held a good position. Will we await an attack or retire during the night? Of the latter I was confident, judging by what I saw and heard. Fires were kept up along the whole line, and some of the boys, worn out with fasting and marching, wrapped themselves in their blankets and lay down and slept. But there was no sleep for me, and there I sat, listening to every sound, watching every move. Two trains of cars, heavily loaded with supplies, crept slowly away toward Knoxville, the very engines seeming to hold their breath fearful of exciting suspicion. The distant rattle of wheels told me the wagon train was falling into line, and the bright glare of fire at the depot spoke of government property being sacrificed because there was no time to remove it. At 2 o’clock I heard the artillery on the hill near us, and which we were supporting, move away and join the train. A few minutes later we followed the artillery, silent as an army of spectres. Our regimental Surgeon and his staff occupied a tent a few rods in the rear of the regiment. Before we had proceeded a dozen yards I missed them and asked our Captain if they had gone on ahead. He seemed puzzled, as their place was in the rear. Perhaps, he said, they were not notified —had been overlooked in the confusion—if so, they will be captured. I asked permission to go back and warn them of their danger. I found them soundly sleeping in their tent, aroused them, and in a few hurried whispers explained the situation—then struck across the fields for the Knoxville road. About two miles distant we came across a body of troops resting beside stacked arms. Near by we found our regiment, and all was well.

14th. After breakfast bugle sounded and tents were struck, horses saddled and 2nd Ohio moved to St. Clair, 9 miles distant. Moved qrs. up near Hdqrs. Rainy day, very during the night. Went down and saw the colored men dance jigs and reels. Quite a jolly time. Commenced messing with Com’ry detail. Good time. Heavy shower.

Saturday, 14th—The weather is quite warm, but windy and smoky. Wild grapes are still growing. There is no change; all is quiet and no news. We still maintain our regular picket of two thousand men.

November 14 — This morning we were ordered back to Orange Court House to report to the battalion of horse artillery again. We started for Orange Court House and marched about twelve miles to-day, and camped about nine miles west of Spottsylvania Court House.

We exult very much over Massachusetts and her verdict. She has not left treason a hiding place in her limits.

Charles Francis Adams, Jr., to Henry Adams

Boston, November 14, 1864

I am disposed to believe that I have just witnessed the most sublime moral spectacle of all time. As you know I got home in time to throw my vote and found myself one of some 5000 superfluous majority in the solid city of Boston. Think of it! The state of Massachusetts, as the result of four years of war and bloodshed and taxes and paper money, reviews her action and declares it good, and reordains the ministers of that action by a majority hitherto unknown in her annals. I never saw a more orderly election. I never saw people after an election settle down to its results with so little discussion, exultation or noise. All seemed to breathe more freely when the result was known, but there was a sober serious tinge in the general feeling not usually noticed. We exult very much over Massachusetts and her verdict. She has not left treason a hiding place in her limits. I cannot but attribute the unanimity of that result to Mr. Everett’s manly and decided course. For the influences which led to it do not seem to have gone beyond the State, and the most surprising changes are to be found in the strongholds of the old Bell-Everett party. He seems to have carried with him the bulk of his party, and left to the opposition only its stock leaders and organ. I delight and triumph over some of the dead in this struggle, e.g. R. C. Winthrop. During the last fifteen years our old Commonwealth has been not infrequently sorely tried. Few of her children were silent when Sumner was assailed, and fewer still when Sumter surrendered. One of these few was Winthrop. In our moments of anger and sorrow and exultation he could not find his voice, or even make a sign; but at last, when the traitors within struck hands with the traitors without, and it seemed possible that the nation might soon cashier its own good name, then, at last, Winthrop found his voice and his strength, and spoke forth in company with Rynders and Wood; he made haste, to affiliate himself with traitors, and, verily, he has his reward.

Thus you see we are very gay over the election, and make out to count the living and the dead. We do not see that it has left us anything to be desired. We have the popular majority, two-thirds and over of Congress, and not one single State Executive, except New Jersey, that is not in harmony with the Administration. I do not see why now the rebellion should not be crushed out. This election has relieved us of the fire in the rear and now we can devote an undivided attention to the remnants of the Confederacy. As for you and for most of us, it is a new and not unnecessary lesson. Here we have for months been deploring this election. We have regarded it as an indisputable misfortune and considered its occurrence now as an incident from which much evil might ensue and no good could. The clouds we so much dread have in this case indeed been big with mercy. This election has ratified our course at its most doubtful stage and it has crushed domestic treason as no other power could have. It is very pleasant to us to think how cheering these tidings will be to you. Abroad this election can hardly fail to produce a greater effect than any victory in the field or military movement. It is not only a great moral spectacle but a decisive moral victory, and the world, I should say, could hardly fail to admire the people who have achieved it. . . .

Sweden’s Cove, Tenn., Saturday, Nov. 14. Reveille sounded at 5 A. M. A very dark and cloudy morning, not a star to be seen or ray of daylight. Fed our hard-worked horses a scant feed of twelve ears of corn to a team, cleaned them off and harnessed, Coffee and crackers for breakfast. 2nd Brigade stationed in front. Followed the 2nd. Camped at the foot of the hill last night. Commenced to rain very heavy as we hitched up and it continued until noon, with loud peals of thunder and vivid lightning. The road ran along the summit for about five miles which was very muddy and hard to travel. Commenced the descent about 1 P. M. which was not as laborious but far more dangerous. The cavalry that crossed let the wagons down by rope, but we locked wheels, and about two miles brought us to the bottom, very stony and steeper than the other side. So we were over Raccoon Mountain of the Cumberland Range, considerably higher than Point Judith, and we crossed in the lowest point. We were now in a narrow valley not a mile wide, all under cultivation, but now idle, called “Sweden’s Cove”. The first trace of civilization that met the soldier eye was a hog, the next a corn crib. Due attention paid to both, the cannoneers charged on the pigs and the drivers filled their nose bags. Camped at the headwaters of Battle Creek. Health of all good and spirits also.

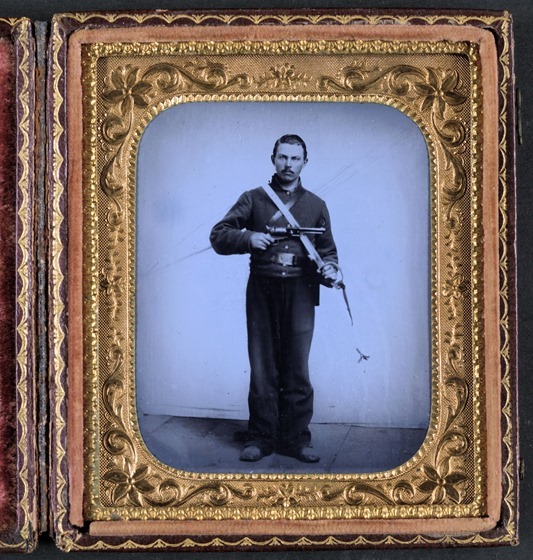

Unidentified soldier in Union cavalry uniform with Colt Dragoon revolver and sword

__________

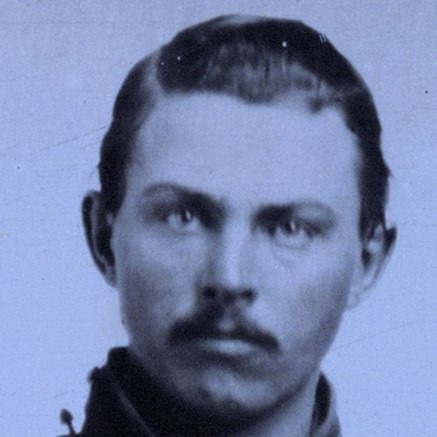

Close-up crop:

__________

Sixth-plate tintype, hand-colored ; 9.2 x 7.9 cm (case)

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs; Ambrotype/Tintype photograph filing series; Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Record page for image is here.

__________

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:fade correction,

Note – This image has been digitally adjusted for one or more of the following:fade correction,

- color, contrast, and/or saturation enhancement

- selected spot and/or scratch removal

- cropped for composition and/or to accentuate subject matter

- straighten image

Civil War Portrait 093

by John Beauchamp Jones

NOVEMBER 14TH.—Some skirmishing between Chattanooga and Knoxville. From prisoners we learn that the enemy at both those places are on half rations, and that Grant intends to attack Bragg soon at LookoutMountain. Either Grant or Bragg must retire, as the present relative positions cannot long be held.

Mr. A. Moseley, formerly editor of the Whig, writes, in response to a letter from the Secretary of War, that he deems our affairs in a rather critical condition. He is perfectly willing to resume his labor, but can see no good to be effected by him. He thinks, however, that the best solution for the financial question would be to cancel the indebtedness of the government to all except foreigners, and call it ($800,000,000) a contribution to the wars—and the sacrifices would be pretty equally distributed. He suggests the formation of an army, quietly, this winter, to invade Pennsylvania next spring, leaving Lee still with his army on this side of the Potomac. Nevertheless, he advises that no time should be lost in securing foreign aid, while we are still able to offer some equivalents, and before the enemy gets us more in his power. Rather submit to terms with France and England, or with either, than submission to the United States. Such are the opinions of a sagacious and experienced editor.

Another letter from Brig.-Gen. Meredith, Fortress Monroe, was received to-day, with a report of an agent on the condition of the prisoners at Fort Delaware. By this report it appears our men get meat three times a day—coffee, tea, molasses, chicken soup, fried mush, etc. But it is not stated how much they get. The agent says they confess themselves satisfied. Clothing, it would appear, is also issued them, and they have comfortable sleeping beds, etc. He says several of our surgeons propose taking the oath of allegiance, first resigning, provided they are permitted to visit their families. Gen. M. asks for a similar report of the rations, etc. served the Federal prisoners here, with an avowed purpose of retaliation, provided the accounts of their condition be true. I know not what response will be made; but our surgeon-general recommends an inspection and report. They are getting sweet potatoes now, and generally they get bread and beef daily, when our Commissary-General Northrop has them. But sometimes they have little or no meat for a day or so at a time—and occasionally they have bread only once a day. It is difficult to feed them, and I hope they will be exchanged soon. But Northrop says our own soldiers must soon learn to do without meat; and but few of us have little prospect of getting enough to eat this winter. My family had a fine dinner to-day—the only one for months. As for clothes, we are as shabby as Italian lazzaronis—with no prospect whatever of replenished wardrobe, unless some European power will come and take us, as the French have done Mexico.

November 14.—The farmers of Warren, Franklin, and Johnson counties, N. C, having refused to pay the rebel tax in kind by delivering the government’s tenth to the quartermaster-general, James A. Seddon, the Secretary of War, issued the following letter of instructions to that officer:

“It is true the law requires farmers to deliver their tenth at depots not more than eight miles from the place of production; but your published order requesting them for the purpose of supplying the immediate wants of the army, to deliver at the depots named, although at a greater distance than eight miles, and offering to pay for the transportation in excess of that distance, is so reasonable that no good citizen would refuse to comply with it.

“You will, therefore, promulgate an addition to your former order, requiring producers to deliver their quotas at the depots nearest to them by a specified day, and notifying them that in case of their refusal or neglect to comply therewith, the Government will provide the necessary transportation at the expense of the delinquents, and collect said expense by an immediate levy on their productions, calculating their value at the rates allowed in cases of impressment.

“If it becomes necessary to furnish transportation, the necessary teams, teamsters, etc., must be impressed as in ordinary cases.

“All persons detected in secreting articles subject to the tax, or in deceiving as to the quantity produced by them, should be made to suffer the confiscation of all such property found belonging to them.

“The people in the counties named, and in fact nearly all the western counties of that State, have ever evinced a disposition to cavil at, and even resist the measures of the Government, and it is quite time that they, and all others similarly disposed, should be dealt by with becoming rigor. Now that our energies are taxed to the utmost to subsist our armies, it will not do to be defrauded of this much-needed tax. If necessary, force must be employed for its collection. Let striking examples be made of a few of the rogues, and I think the rest will respond promptly.”

—Major-General Schofield, from the headquarters of the Department of the Missouri, at St. Louis, issued an important order regarding the enlisting of colored troops.