Sunday, March 15th [1863]. Mrs. Dameron’s little ones came over to breakfast. I predict that Mary Lu, or Yete, as she is called, will one day make a sweet, pretty and ingenuous woman. She is shy now, not demonstrative—not half so much noticed and petted as her sister Sydney. The latter is very communicative—she is very pretty, and as much at her ease as a grown woman and quite as worldly-minded and fond of show as some of them. She will be a coquette, I fancy, and will give her good, religious papa the heartache often. Mrs. Dameron with all the children (the baby born the night the city fell, while the Yankee gunboats were steaming up the river; a beautiful boy who has never yet seen his papa) passed yesterday with us, as did also Mrs. White. Courtnay, a fine boy whom they call Chopper(?). The little folk were quite noisy, and their peaceful-minded mother looked as well, calm and contented as if all the world were so, too. She is so honest-minded, so true, innocent and unworldly, that one cannot respect her too highly. She has a kind, good husband—but he went out with the Confederate guards, when General Soule carried them off and has not been back since. She hears often by what we “Rebels” call the “underground railroad,” and the “grapevine telegraph.” He is not in the army, but in the Commissary Department. His friend, Mr. Broadwell (Colonel, they call him, though not in service), being a sort of head man in Jackson—he, Colonel B , being a friend of President Davis, and in great trust with him, can procure favors for his friends. I do not think they will ever fall on one more worthy than Mr. Dameron— a good husband, son and brother. Mr. Broadwell was quite a neighborhood card when in the city— he is very rich, very useful to the Government, and I believe is making a still greater fortune now. He is honest, however, and his word is law, they say, in Jackson, now a military depot. He is awfully uninteresting—and I believe would be literally the death of me were I forced to entertain him long at a time. Why are useful people often so uninteresting? This man is “strong and healthy,” I say, “and ought to be in the field where so many of our delicate brothers are risking health and losing fortune.” Mr. B—— bears the title of Colonel. Then why is he in the Commissary Department?

To-day I thought I would not go to church, but stay at home and have a quiet time. Mary Ogden came first—I was glad to see her; she loves us and we love her. Then came Mrs. Dameron; then Mrs. Roselius, after she left, Mary Ogden, who had gone out, came back to dinner. She left on the three o’clock car. Doctor Fenner then arrived. Then Mrs. Norton read aloud out of newspapers, and Ginnie laid down her book with a sigh— and I, how can I possibly string together a sensible sentence! Mrs. White and Mrs. Dameron are in the other room now, if no one comes after them. I will record what Mary O—— told me in the greatest secrecy. I fear to write it. If anything should happen, will I have time to burn this record! A spy of Stonewall Jackson’s has been in this town—within this week—being known to ——; has been at his house.

He has worn the Federal uniform during his stay and has taken away all necessary information. This man is no impostor, having been seen by in Virginia last summer—he is the Captain in which ——’s son has been first lieutenant since this young man has been on detached service. The spy is well known to —— and they therefore believe what he says. He brings the astounding intelligence that Stonewall Jackson is now at Pontchatoula disguised as a wagoner! He says that when he met him he called him General, whereupon Stonewall disclaimed the honor. “You can not deceive me, General,” said he, “I served under you too long.” He was after this appointed spy. This city is to be taken back before long, unless, indeed, we should be beaten in the coming contests of Port Hudson and Vicksburg. Mary imparted this information almost with fear and trembling to us and made us promise most sacredly to not even whisper or look it to another. Ginnie and myself are the only two in all the world that she would even whisper it to, she says. Her father would be half crazy if he knew anyone else knew of this visit. I have heard so much of Confederate attacks on this place, that such reports do not excite me now. This young man’s story I would doubt altogether if had not known him and seen him in service in Virginia. Time will prove. I wish I could realize him and what he says as Mary does. There are many rumors of Stonewall’s being outside somewhere near. One reliable “lady” knows from a “reliable” gentleman that he is within five miles of the city and bent on its attack. Mr. Randolph says he heard two Federals in the car say, “Well, who knows that that old Stonewall won’t burst in on this city any day. Well, well, we must admit that Stonewall and Longstreet are two powerful men. Powerful men!”

Why should Jackson be in disguise, when his very name at Port Hudson would make our army there invincible? I can offer no solution but this: if it should be known in Virginia, the effect on our army there might be dispiriting. He is so idolized by his men and so feared by the enemy. Even the cold Englishman, whose account of this hero I read a few days ago, says that he could be led anywhere under the inspiring influence of two such men as Lee and Stonewall Jackson. I am so glad that dear Claude’s short military career was passed under him. Claude was one of the famous “Foot Cavalry” until he left his poor arm at Port Republic. Taylor’s Brigade, Harry Hays and the Seventh Regiment Crescent Rifles are names doubly dear for Claude’s sake. I have now in my desk a letter of Claude’s—of last year—written in pencil on a cartridge box— which says: “We have just given Banks a complete whipping—I expect we have done rather a brilliant thing.” Banks will get another whipping soon, in a few days, we think, though the Federals have it reported that Port Hudson has already been evacuated by our troops—frightened at their approach, perhaps. ‘Tis said by our people that fighting is going on to-day. (N. B.—Mrs. Norton reading Bible aloud.) We have just held a discussion—we have expressed a wish that we might get this place by treaty—this humane desire gives offence to Mrs. N——. She “wants them killed.”

She wants to “hear the cannon—let ’em come from France or wherever they will.” If a forcible entry of this town will help to hasten the end of this terrible war, I will be glad to see it—and that speedily—but if our successes which have gained us the admiration of the world, could only buy our freedom without more bloodshed, would it not be better! Oh, I long, long to see this cruel war over! I do not like to even hear of the sufferings our enemies endure. The meeting of the two huge armies now on the river, bent on annihilating each other is a terrible matter to think of. It seems to me I have no longer any faith in civilization, learning, religion—anything good. (If I should write down a scrap of the Bible here, do not let it astonish you, my little niece—your auntie is very seldom alone. Nobody means to inflict any ill upon her, but she is talked to, or read to, almost every minute in the day from before breakfast to bed time.) Who knows what a fine journal I might not have written you if I had had the health and spirits to go about much, and had the privacy in which to record what I heard.

Mrs. Norton went yesterday to get papers for her negroes, according to Federal command—was quite astonished to be asked if she had taken the oath. In giving answer, she also managed to give offence to the official, who rudely told her to “Hush,” whereupon she told him she would talk as much as she pleased in spite of all the Federals in New Orleans and not take the oath either. The Federal said he didn’t care a damn whether she took the oath or not. She then made a very proper answer—”You have proved a gentleman of the first stamp, sir,” said she, “in swearing at an old lady; a very fine gentleman indeed.” He was then silent and ashamed. Mrs. Dameron, Mrs. Doctor Stille and Mrs. Wells all went to the same place to get papers for their servants and were treated very politely. To those who had not taken the oath he expressed great regret, that he was compelled not to issue passes for servants belonging to disloyal people. Such servants are all caught up and forced by Federal soldiers to work on the fortifications and plantations. I pity poor Julie Ann; I wonder what death she will die! She has never known real hardship. This step of the authorities here has given the negroes a great blow. So much for Federal philanthropy! Another instance of it. The Yankee Era said yesterday that the Indianola before her capture by the Confederates had been dispatched to destroy the cotton and plantation of Jeff Davis and his brother and to bring off all the male slaves— the male slaves, philanthropy! We hear constantly of negroes who are brought away unwillingly from their home comforts and their masters—and not infrequently are these poor people robbed of all they have by their pretended saviors. Mrs. Wilkinson’s old man was robbed on his plantation of his watch and money, and another of four hundred dollars, which had been hoarded up for a long time. It’s bad enough for a soldier to steal chickens and pigs, yet I have in some sort a sympathy for this sort of outrage, but when I think of how these pretended civilizers and benefactors have ransacked this town for fine linen and silver spoons—letting not even negroes escape—I feel glad enough to have ceased calling Federal soldiers brothers and countrymen. The dear old Union has ceased to be dear to all who would have once died for it. Its defenders are not knights or cavaliers, but robbers. I am growing each day fonder of our new flag. I did not love it at first—but my heart was thrilled at the accounts of our gallant Southern heroes. I am proud to hear what brave and honorable gentlemen they are, though too often clothed in homespun and too often shoeless.

Read an account in the New York World of the sinking of the Hatteras by the Alabama. It is given out by the officers of the Hatteras on their return to New York. The short conflict was thrillingly interesting. I fancy I can hear Semmes call out, “Do you want assistance!” to the sinking crew—and the awful moments that followed the inquiry. The paper says, “Every comfort was provided for both officers and men” on board the Alabama, and every attention was paid to the littlest wants of the prisoners. Cots were erected on the spar deck for the wounded in order to give them fresh air, and the surgeon of the Alabama extended every facility in their power, furnishing all sorts of medicinal stores for the use of the wounded. A guard was placed round the sick and wounded, and all on board prohibited from making a noise. Some of the Rebel officers gave up their sleeping accommodations; treated them with the utmost courtesy and consideration.” In the Yucatan channel the Alabama ran up to a strange vessel which they ascertained to be English. The Confederate flag was then hoisted and the English vessel dipped her colors three times in token of respect. At Port Royal many British residents and others came on board greeting the officers of the 290 warmly— “We are glad to see you; our whole hearts are with you.” Handshakings and congratulations were exchanged all around and the Southern Confederacy and its representatives were exalted to the skies. Her Brittanic Majesty’s steamer Greyhound was in port, and when it was known on board this vessel that the Alabama was there, it was proposed to greet her with “Dixie Land” and the band struck up. Hearing this air, Semmes remarked to some of the Union officers, “Do you hear that greeting to the lone wanderer of the seas? That is what we hear everywhere.” The English and other visitors on board the Alabama spoke contemptuously of the Yankees, and the Yankee Government before the Union prisoners. “Contemptible Yankees,” was their mildest appellation. This, I think, was mean. The feelings of the unfortunate should never be wounded. The officers of the Hatteras had only done their duty. I am glad that on the Alabama and our other war vessels, that prisoners are treated with respect and kindness. Such things are the triumphs of civilization.

The New York papers are indignant at the sympathy we receive. Indeed, it is wonderful how our young Confederacy has sustained itself with a new and untried government; a volunteer army comprised of men unused to hardship or discipline; many of them high-blooded young fellows who cannot be prone to bear meekly the harshness of officers; with ports blockaded; shut out from not only comforts—but needs; badly clad; poorly armed and coarsely fed; cut off from all United States natural resources; without navy or arsenal—yet have we defied the enemy and preserved our border line almost unbroken. These are triumphs indeed, and it is a grand thing to feel that our countrymen are endowed with faculties which ripen under misfortune and trial, with an enthusiasm which ennobles their deeds, and a courage which is the best of foundations both for national and social character. But, alas! will not this Southern Confederacy be torn asunder sometime as the once sacred Union now is! I want to love all the States with the same love. I used to honor all American soil from Maine to Georgia. I have had a great blow in the severing of the old States and it seems to me that the security has gone from all things. No Constitution made by man could be better or nobler than that our old fathers framed—yet how was it trampled on! There will not be, I fear, in future years any better security against the machinations of bad politicians than there has been in the present time, and here among us may arise some other Lincoln-like demagogue to whom our people will yield their liberties and self-respect as the Northern people have yielded theirs. The separation of States and the blood shedding and suffering of a people will be the consequence. Texas, I fear, will certainly form a republic of her own. There are enough of Texan hearts still beating who regretted the old Union with the United States, though no soldiers have borne more nobly the arms of the Confederacy with honor than those of Texas. They have been distinguished on every field. Talking of Texas stirs in my heart the ever-longing to see my loved ones there. My sister and her dear little ones; my brothers— more especially poor, wounded Claude. No letter or word can reach us from there. I fear my many efforts to smuggle scraps of paper through to them have failed. I have a spool of cotton in which I propose to send a few lines when the Wilkinsons go, but they will wait now I suppose until Port Hudson falls or is pronounced impregnable.

“While I was sick Mrs. Roselius brought over a photograph of a large picture painted here last summer in great secrecy. It was to be sent to Europe to give an idea to the people there what Butler was doing in this conquered city. While Butler was here he seemed almost insane on the subject of enriching himself. He was not content in robbing people of their wealth and women of their jewels and silver; he opened several graves, supposing that gold had been hidden in them. It was thought that he was led on to these searches by the reports of negroes. It is well known here that he opened the grave of our well-loved hero, Sydney A. Johnston (killed at Shiloh). This picture, therefore, represents a graveyard, with the inscription on several tombs very distinct—Sydney A. Johnston, Charles Dreux and the Washington Artillery. On the steps of one of the tombs sits, with back erect, a huge and hideous hyena, with Butler‘s head. A skull and several bones lie near. The effect is sickening and appalling. When I looked at it the same sick feeling came over me of dread and horror that I had felt the day that the wretched thing was done—when Mrs. Brown came up and whispered what Butler was doing and whom he had last seized, and a creeping horror made us all feel the power and wickedness of the wretch to whom we had yielded the city. Over this picture appear the words, “Great Federal Menagerie now on exhibition,” and beneath, “The Great Massachusetts Hyena—true to his traditional instincts, he violates the Grave.” It would have been death last summer to have been caught painting this picture as it would have been to have been known to know anything about it; Mrs. Brown having whispered it to us, though not to her mother. I never saw it until Mrs. Roselius brought it over—she seemed quite astonished to hear we knew anything of it. This picture on a large scale, exhibited over the civilized world would be certainly a greater though more refined punishment than hanging or tearing to pieces by a mob would be for Butler, with which he is so often threatened in private conversation. I do not like violent measures of any sort which inflict physical torture, but I do think that a wretch like Benjamin Butler should be held up to the execration of the entire civilized world. Such rebukes must turn the most hardened villain’s eye inward, and moreover they act wholesomely on others. There should be no revenge in punishment in a civilized society; punishments should be administered for their effect merely for prevention of crimes.

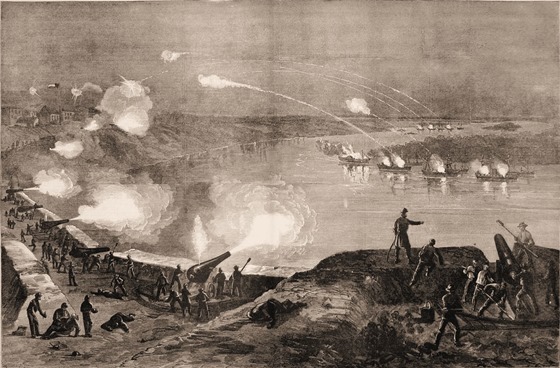

Mrs. Wells has paid us a visit. Reports that Farragut has passed by Port Hudson. Great rejoicing among the Yankees. Mrs. Wells, who has been on a long visit to Mrs. Montgomery, has told us so much of the quiet charities done by both Mrs. Montgomery and the Judge. I was glad to hear it, as they are very rich and as they entertain but little, are thought mean generally. They are very kind to Confederate soldiers, taking them in, nursing them, clothing them and giving them money. People never have any right to pronounce on human character, at least until it has been brought under close inspection. So many are overrated because of some manner that may be entirely superficial and deceptive as to the character it conceals. Mrs. Norton has been down town—brings the Yankee Era. Farragut has passed with two vessels, the flagship Hartford and one other. The Mississippi was destroyed by our batteries—thirty men killed. Farragut is now expected to be between two fires now that he is separated from the rest of his fleet. His position seems dangerous to us— flanked on one side by Port Hudson and on the other by Vicksburg, and a bold report that he has been captured, is already out. Mr. Dudley was up this afternoon; I was making a sack and made Ginnie go out. It is wrong for us to seclude ourselves as we do, but oh, when one feels wretched, anxious and lonely as I do, how can I wish for anything but solitude. Other people seem to be able to throw off their grief by merely meeting and chatting about it. Mrs. Dameron and Mrs. Norton received letters this afternoon. All are well outside the lines. Mary Lou Harrison wrote to her grandma, so also Charley. They have not heard from Texas—the mails being broken up. Charley says that he sent the letter I sent him to Claude—I suppose by Mr. Riley, who is about to return to Galveston where his father is stationed. I feel so dreadfully being thus cut off from all I love. Mrs. Roselius came in this evening, so did Mrs. White and Mrs. Dameron. I walked a little way home with the two latter, after shutting myself up all day long. Mrs. Roselius promised to get me one of the pictures of Butler as hyena. I should like to have the large oil painting.