Tuesday, March 17th [1863]. Rose this morning feeling very badly. Coughed a great deal last night. Slept but little, but in the short interval dreamed so unhappily that Ginnie awoke me twice, after my having cried out. I was among crowds of people, it seemed, with a heavy weight upon my heart. I was traveling on an immense iron steamer—saw a boy fall over and drown, whereupon I screamed and awoke. After this I could not sleep. Listened long to see if I could hear the guns at Port Hudson. For several nights the firing has been heard by some people. At Greenville Judge Ogden, who was here yesterday, heard them at four o’clock in the morning, distinctly; he got up and waked the girls, who also heard them. The Judge has heard that his son Billy has come to Mississippi from Virginia. He can not tell whether on furlough or with the army. It is reported the 7th Regiment, Crescent Rifles, is outside with Col. Harry Hays and the great Stonewall. These are times of great excitement. This seems to us all the crisis of the struggle. If we are successful in the two coming engagements we hope to have peace at once. If the North fails to open the Mississippi to the Western people and its ports to the world, it is thought that the war must be abandoned. Heaven knows—the people of the North seem demented to me. That they should feel a wild regret for the loss of the Southern States, after having goaded them into resistance, seems natural enough, but that they should think that war and bloodshed will restore the Union, seems but a fanatical dream. No one more sincerely mourned the Union than myself, but to me the separation of the States was the blow. There would be no beauty in union now. And we have too much dear blood to remember now, if not to revenge, ever to be able to go back now. Ah, if Vallandigham had only been president instead of Lincoln! Perhaps these things are all intended—who can tell! The existence or non-existence of a nation cannot be disregarded by the Higher Intelligence. (Mrs. Roselius would regard this expression as a proof of my having gone through a course of infidel reading—she came to this conclusion the other day when she heard me use the term First Cause.)

The black people in the city have met with the most dreadful blow at the hands of their Yankee friends. These poor people have been misled by every wile and persuaded to leave their owners and even in many instances to be insolent to them. I know of a number of instances where they have been promised by the Yankees freedom, riches, free markets, a continual basking in the sun, places in the Legislative Halls, possession of white people’s houses, and a great deal more; of course, these infinite temptations have proved too much for them—they have gone over in numbers to the Yankees, insulting white people in the streets and in houses. They have been protected by Yankee courts here, both in murder and robbery. And after all this they are being picked up singly and collectively and driven by Yankee bayonets to the plantations, where they are to work or be shot down. All servants who have not passes given them by the Yankee authorities, are to be disposed of in this way—and as no pass is granted to any owner who has not taken the oath, a terrible scene of confusion is at work. These Yankees pretend that they have come to restore civilization and justice to this benighted Southern land and assume in all their printed work a vast philanthropic sympathy for the oppressed race; never since the Southern people have owned slaves has the separation of families been carried on on as large scale as now. Indeed negroes have been more protected from separation than white people until now. To-day from forty to fifty colored women, picked up without notification on the streets, were driven at the point of Yankee bayonets on a boat and taken to a plantation. Yankee soldiers seize those even who are with their own mistresses, unless they have Yankee passes. “Have you a pass?” is the question, and if the victim is not so protected, “Fall into line then,” is the response. Among all the crimes Yankee writers have heaped upon us, this cannot be enumerated. Mary, Mrs. Norton’s woman, came to us just now; she is very uneasy about her young daughter Emma, who is hired out. She fears the Yankees will take her off. Indeed, she fears to be taken, too, as she can get no pass, and some houses even have been entered by the soldiers. The insolent negroes who have been boasting of Yankee support are very much crest-fallen and ashamed. One of Mrs. Roselius’s threatened to have a gentleman arrested last week; this week she is powerless.

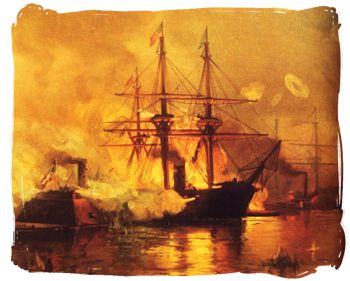

Mary Ogden just in from Greenville—full of news and excited. “It was the Albatross that passed the batteries” and was very much injured—so was the Hartford. Both injured and between two fires. Farragut, they say, has pronounced the attack useless, but makes it because ordered to do so. I really do not suppose he has opened his mouth upon the subject. He is a brave man, this much we all accord him. His family live here, and he was educated, it is said, by one of the charitable institutions of this city. His relatives would not receive him after the city fell, and when the shelling of the city was imminent, he sent word that he would protect them and received in answer that they would not accept his protection. It was reported at the time that his mother was here, but that was untrue; she is dead. I remember laughing at the excited manner in which Martine Ogden exclaimed that the city would be safe. “For surely,” said she, “he won’t shell his mother.”

The Era is filled with insolent braggadocio because Farragut has passed—even in crippled condition. The Yankees have called their military collection in all quarters—”The vast Anaconda,” which is “to crush the rebellion.” We think that Farragut’s being separated from the fleet by powerful batteries looks very much as if the head of the water snake was severed from its body. He said that his ship should pass, though that should be the only one. The town is all excitement—the Yankees here expect an attack. Indeed, if possible, we should make it— the enemy would then have to capitulate. The forts below we could take later. Every hour brings its report. Indeed, it is an awful time, fraught as it is with death and ruin to the majority. The Yankee woman at the corner is in much trouble; we think that she has heard no hopeful news from Baton Rouge. She is all packed to start somewhere at a moment’s notice. Mary Ogden took dinner and passed the afternoon with us. She had been out in the morning to look up some Mrs. Colonel Pinckney, who is just in from the Confederacy, and knows her brother in the army. This lady reports everything going on well outside. She passed through Baton Rouge. On the way she fell in with many Federal soldiers—they volunteered conversation and told her a good deal. She is a daughter of an officer in the old United States’ army, and was brought up in garrison circles, so I presume she knew how to talk to military folk. She learned that the soldiers at Baton Rouge were bent on not fighting—that they were going over to us at the first opportunity. Vicksburg and Jackson are filled with officers and men who have resigned the Federal service. This seems almost incredible, but this war is being held now as both useless, senseless and wicked. Thousands of these soldiers say they do not hate Southern people and that they want to live among them. Two officers left the steamer Mississippi and changed their uniform before that unfortunate vessel left this city.

Late in the evening I took a walk and stopped at Doctor Glenn’s—found Sarah in bed with a roomful of ladies. Her baby is nine days old—called “Robert Lee,” after our great General. Mrs. Pritchard and her daughter were there and told me much of what these Federals are doing in the city. If the United States had chosen to war against the Union, instead of for it, she could not have chosen better people for her service. Three ladies of Mrs. Pritchard’s acquaintance were arrested not long ago and thrown into a room filled with all sorts of horrid people—drunken soldiers and half-dressed ones—for having been singing “The Bonnie Blue Flag” in their own houses with some officers from the British ship. Another lady giving an entertainment to some British officers in her own home had it forcibly entered and was threatened with a search for flags while the company were present. These disgraceful things often happen. Not very long ago an officer rode in among the flowers in Mrs. Budike’s yard, because a child was singing “The Bonnie Blue Flag”—he had the lady called to the balcony, and told her that it was “a pity that United States officers who had worked hard all day could not take a ride for recreation without being insulted by that Rebel song.” Was there ever such nonsense and such a want of pride and dignity. I’m afraid that Mrs. Stewart’s daughters next door will be arrested some day, for their piano and mingled voices are continually doing duty to that contraband ditty. A gentleman of Mrs. Pritchard’s acquaintance has been arrested—he asked Mayor Miller wherefore, “For hanging out a Confederate flag,” said he. “I know the gentleman,” said Mrs. Pritchard, “and I am sure he did no such foolhardy a thing—he would not be guilty of such silly hardihood.” “Oh, well, then,” returned this easy-natured upstart, “he must have had one somewhere in his house, and besides he has been circulating these obnoxious poems,” meaning the “Battle of the Handkerchiefs” and a prose article purporting to be an official report of one of Banks’ men. The town is flooded with these articles—some of them very cutting. The Federals can not find out their authors or the place of their publishing.

Mrs. Callender has just been in; says she is going to the funeral of Commander Cummings, who was killed up the river when Farragut passed. We told her she would be taken for one of the mourners. She laughed. Colonel Clarke, the only gentleman among the Federals, has been wounded, some say seriously; his death is even reported. There appears to be much regret for him among our people, and if he is brought here our women intend to do all in their power for him, to show their grateful distinction between himself and others.