2d.—The battle continued yesterday near the field of the day before. We gained the day! For this victory we are most thankful. The enemy were repulsed with fearful loss; but our loss was great. The wounded were brought until a late hour last night, and to-day the hospitals have been crowded with ladies, offering their services to nurse, and the streets are filled with servants darting about, with waiters covered with snowy napkins, carrying refreshments of all kinds to the wounded. Many of the sick, wounded, and weary are in private houses. The roar of the cannon has ceased. Can we hope that the enemy will now retire? General Pettigrew is missing—it is thought captured. So many others “missing,” never, never to be found! Oh, Lord, how long! How long are we to be a prey to the most heartless of foes? Thousands are slain, and yet we seem no nearer the end than when we began!!

Saturday, June 2, 2012

“So many others ‘missing,’ never, never to be found!”—Diary of a Southern Refugee, Judith White McGuire.

JUNE 2D.—Great indignation is expressed by the generals in the field at the tales told of the heroism of the amateur fighters. They say _____ stripped a dead colonel, and was never in reach of the enemy’s guns. Moreover, the civilians in arms kept at such a distance from danger that their balls fell among our own men, and wounded some of them! An order has been issued by one of the major-generals, that hereafter any stragglers on the field of battle shall be shot. No civilians are to be permitted to be there at all, unless they go into the ranks.

Gen. Johnston is wounded — badly wounded, but not mortally. It is his misfortune to be wounded in almost every battle he fights. Nevertheless, he has gained a glorious victory. Our loss in killed and wounded will not exceed 5000; while the enemy’s killed, wounded, and prisoners will not fall short of 13,000. They lost, besides, many guns, tents, and stores—all wrung from them at the point of the bayonet, and in spite of their formidable abattis. Prisoners taken on the field say: “The Southern soldiers would charge into hell if there was a battery before them—and they would take it from a legion of devils!” The moral effect of this victory must be great. The enemy have been taught that none of the engines of destruction that can be wielded against us, will prevent us from taking their batteries ; and so, hereafter, when we charge upon them, they might as well run away from their own guns.

Monday, 2d—I was one of a hundred men detailed to clean up our camp ground. Pope’s men who went in pursuit of the rebels are returning and going into camp in and around Corinth. I spent $1.00 for peaches and bread at the sutler’s tent.

June 2—We received some visitors from home.

June 2 — It rained all last night, and we were lying in it without tents. At daylight we renewed our march up the Valley. The road was very muddy and slushy.

We overtook Jackson’s wagon train again, which thronged the road and moved slowly. I think that a shell or two in the right place would increase the speed of his trains, which would be highly beneficial just now to all concerned, as the Yanks are pressing our rear and itching for a fight. One mile south of Edenburg, on a commanding hill, we halted and went in position, which we held till nearly night. While we were there we heard cannon firing, which seemed to be below Woodstock. Quartered in a barn near Red Banks.

Flat Top Mountain, June 2, 1862. Monday. — A clear, hot, healthy summer day. General McClellan telegraphs that he has had a “desperate battle”; a part of his army across the Chickahominy, is attacked “by superior numbers”; they “unaccountably break”; our loss heavy, the enemy’s “must be enormous”; enemy “took advantage of the terrible storm.” All this is not very satisfactory. General McClellan’s right wing is caught on the wrong side of a creek raised by the rains, loses its “guns and baggage.” A great disaster is prevented; this is all, but it will demonstrate that the days of Bull Run are past.

2nd. Passed a Catholic Mission for Indians. Very good conveniences. Many children. Three or four buildings. Stopped often to graze. Passed through a good country. Good oak and hickory timber. Passed an Indian village—Osages. Encamped upon a good plat of grass along the Neosho. After supper went to the river and bathed. Received invoice of provisions from “Buckshot.”

Camp near New Bridge, Hanover Co., Va.,

Camp near New Bridge, Hanover Co., Va.,

Monday, June 2, 1862.

Dear Brother and Sister:—

Before this reaches you, you will have heard of the battle of Hanover Court House, and I know you will be very anxious to hear from me. I should have written before, but my time has been so taken up and I have been so worn out by the extraordinary exertions of the past week that really I could not. In fact. I can scarcely write to-day.

Last Tuesday morning at 3:30 o’clock we were called out and formed in line without time to get breakfast. It was raining great guns and continued to rain till 10 o’clock and the rest of the day was intensely hot. We took a blanket and tent, three days’ rations and sixty rounds of cartridges and started, we knew not where, and cared not, only that we went toward secesh. We had the hardest march we have ever had yet, over twenty miles through mud, swamp and cornfield, fording creeks and climbing hills. Officers and men gave out, unable to go further. Four captains, ours included, and a half a score of lieutenants, gave up and still we kept on at a killing pace. At last we came up to them. The Twenty-fifth New York was ahead and was the first fired on, which they returned with interest. Then our brigade and a battery. The rebels, of course, were in the woods and we in the field, but they were driven out and we drove them over two miles to the north and then turned, supposing the fighting was all over. In this we were mistaken. A train of cars from the south brought reinforcements to the enemy, and, when our boys were half way back, the rebels, six regiments strong, attacked the Forty-fourth and Twenty-fifth, which had not joined in the chase. They stood their ground well, though they were terribly cut up, but a came to the rescue. On came the brigade and poured in a fire that quickly caused the discomfited secesh to beat a retreat. They were totally routed. Here then is the amount of the day’s work—a forced march, three separate fights and three victories, with a loss on our side of three hundred and seventy-nine in killed, wounded and prisoners—fifty-three killed, over one thousand rebels ditto, and over two thousand prisoners, North Carolina and Georgia troops. The Eighty-third lost two killed and thirteen wounded. Sergeant Hulbert and Frank McBride in Company K were both shot in the foot. Sergeant H. loses his foot and Frank his toes, the only casualties in our company.

I cannot tell you how I felt that day. As long as there was any prospect of a fight I kept my place in the ranks, but, when we gave up the chase and turned back to where our blankets were left, I fell out to get some water and bathe my head. My tongue was swollen with the heat and thirst, and I so faint I could hardly stand. I followed on, however, but the regiment was some distance ahead. I came up to Denny and Henry. Henry could not walk but a little way without stopping, and Denny and I waited for him and helped him along, but soon we heard the sharp rattle of musketry ahead and the third fight had commenced. We tried to get Henry along, but finally left him and he came on slowly while Denny and I pushed on as fast as we could, but the firing was done when we caught up. The regiment was in line in a very large wheat field and the rebels in the woods beyond. The balls whistled round us, but none touched me, so I am perfectly safe, but I was so worn out that I have not felt right since. Night closed in and we went back to our blankets and, wrapping up, lay down between the rows of corn to sleep. Generals and privates alike spent the night on the ground. Morning came, and stiff and sore we rose. The work of collecting and burying the dead was soon commenced. The woods were full of dead rebels who lay, as they fell, in all shapes. They were carried out and laid in a ghastly row on the grass. One fine looking young man was shot through the heart as he was loading his gun. His hands had not changed their position, one extended above his head drawing his rammer and the other grasping his gun by his side. His eyes were open and the expression of his countenance as calm as though he was sleeping, but the fearful wound in his breast told that he would never wake on earth again. We buried over one hundred of them. We spent the day in recruiting our exhausted soldiers. General Porter gave permission to stay and eat, and, if an army ever made havoc with an enemy’s provisions, we did. We killed all the beef, pork, veal, mutton and poultry we could eat and carry away. We captured a train of cars loaded with supplies for the rebels, and our regiment got over fifteen hundred pounds of sugar and nearly a ton of splendid tobacco, which will all be given to the men. Secesh knapsacks were scattered everywhere, and our boys, if they could have carried away the things, would have got a good many comforts, but we could not. We got a good many love letters, etc., bowie knives and pistols, and I got a great bowie but I threw it away, I couldn’t carry it. I send you a letter that I got in a knapsack, and a secesh stamp. The letter is an excellent specimen of secesh literature and love. I almost wish I had as fond a sweetheart. We retraced that long weary march on Thursday night, arriving in camp at 3 o’clock in the morning. On Saturday night we were ordered out at midnight and went out to the Chickahominy. We came back yesterday afternoon. Lowe’s balloon is up in our camp watching the rebels and the report is that they are all leaving Richmond. I have heard no firing to-day and we are expecting orders to follow them every minute. I must close. Goodbye. Write very soon to your brother Oliver. Direct Company K, Eighty-third Pennsylvania Volunteers, Morell’s Division, Porter’s Corps, Army before Richmond, Va.

Dear A.,—The “Daniel Webster” is filling, to sail to-night. This letter shall go in her. What a day and night we have had! What a whirlwind of work, sad work, we have been in! Immediately after closing my letter of yesterday, Mrs. Griffin and I were whisked away in a little boat, at the peril of our lives, and hustled, tumbled, hoisted, first into the “State of Maine,” where we lost our way amid frightful scenes, until we finally reached the “Elm City,” where we were going as night-watch to relieve the ladies belonging to her, who had been up all the night before. She had four hundred and seventy wounded men on board. We passed the night up to our elbows in beef-tea, milk-punch, lemonade, panada, etc. The men were comfortable. The surgeons let them, for the most part, have a night’s rest before their wounds were opened. Not so, however, on the “State of Maine,” where operations were going on all night; the hideous sounds filling our ears even in the midst of our own press of work.

Our men were so touchingly grateful. There was a poor fellow lying close to the door of the pantry where we were making and dispensing the food and drinks: his leg was amputated. I noticed, after a time, that he was stretching and straining to get at a bundle or something in his berth. I went to him as soon as I could. He turned his face to me, covered with tears, and put a little crumpled roll of pink paper into my hand, saying: “I heard you tell that man you gave him the last pin out of your dress: don’t give us everything; please take these,” — precious little roll! will I ever part with it! Such things are better for us than all the quinine in the country. We stayed chiefly in our pantry, giving out to the dressers and nurses all that was wanted; also to a detail who came from time to time from the “State of Maine.”

Oh, when shall I forget the sunrise that morning as it looked in through the little window beside me! When can I cease to remember the feelings with which I saw it!

Mr. Olmsted sent peremptory orders at nine o’clock that we should return home; and we left the “Elm City,” sure that the men had everything needful, and were safe in the faithful hands of Mrs. Balestier and Miss Charlotte Bradford. We were no sooner washed and dressed than the “Small ” scudded up to the landing to take on forty wounded just arriving by the railroad. The forty proved, as usual, to be eighty,— ghastly objects: this was like being on a battle-field. The men were just as they fell, in their muddy clothing, saturated with blood and filth. From then until now, when we have just put them on the “Webster,” Mrs. Griffin and I have been with them. One died in her care, and one in mine; there were some too far gone to know anything more in this world, but there were others, almost as badly hurt, who were cheerful, bright, and even talkative, — so different from the dreary sadness and listlessness of sick men. They seldom groan, except when their wounds are being dressed, and then their cries are agonizing: “Oh, doctor, doctor!” in such heartrending tones.

General Devens, wounded in the knee, Colonel Briggs, Tenth Massachusetts, wounded in the thigh, and several other wounded officers, were among the eighty; but they had their staff-officers or orderlies, and though we saw that they had what was necessary, we stayed ourselves with the men. We have just put part of them on the “Webster,” which sails for Boston this evening, and the rest on the “Elm City,” which sails for Annapolis at the same time. The “Spaulding” has just come up the river, and the quartermaster hails me that there are cases on board for me. Thank you all! Dr. Grymes has invited us to dinner on the “Webster,” that we may swallow necessary food, which we could not do on the polluted decks of the “Small.”

The trouble the medical authorities give Mr. Olmsted is terrible. They send the most conflicting orders, and there is no United States medical officer here, at this most important point, to refer to. Captain Sawtelle, Assistant Quartermaster, is so good to us. He and Colonel Ingalls and General Van Vliet are constantly shielding the Commission from annoyance. How nobly the Commission has done its work, how thoroughly, how wisely; with what lavish disregard of labor and care and fatigue, so long as the best possible is done for the service! Day and night, without sleep, sometimes without food, Mr. Olmsted and Mr. Knapp are working their brains and their physical strength to the utmost. Good-by! we are just going on board the “Webster.” No, we have only run alongside to give her the order to sail. So good-by to our dinner! I hoped to have sent this letter by her. The victory is a victory; but oh, the lives and the suffering it has cost!

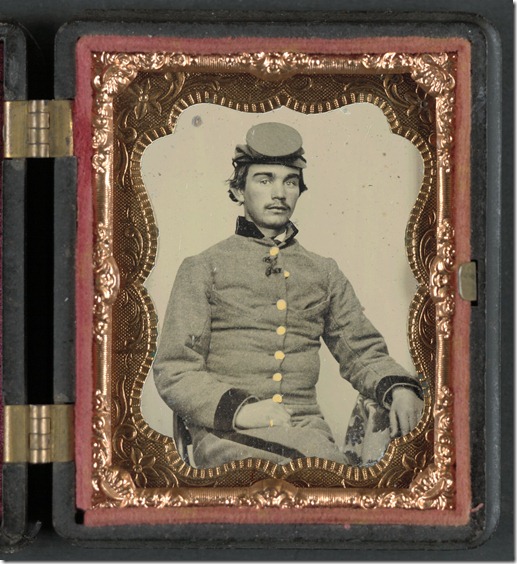

John W. Anthony of Company B, 11th Virginia Infantry Regiment, Southern Guards

Photograph shows identified soldier, John W. Anthony, who enlisted in Company I, 2nd Virginia Cavalry Regiment, and then in Company B, 11th Virginia Infantry Regiment, as a private and was later promoted to sergeant.

A letter from John W. Anthony to Ma, Pa & Callie, June 2, 1862, is also at the Library of Congress, but is not available online.

Liljenquist Family Collection of Civil War Photographs. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs DivisionWashington, D.C. 20540 USA

Record page for this image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011647974/

Embracing the History of CAMPBELL COUNTY, VIRGINIA

Southern Guard (Company B) 11th Va. Reg. C. S. Army Roll Enrolled at Yellow Branch, Campbell County:

Private John W. Anthony, wounded at Seven Pines and Manassas

Note: The photograph part of this image has been lightly enhanced, primarily to correct for fading.