June 6 — Early this morning we left camp and passed through Harrisonburg, turning off of the Valley pike half a mile above town on the Port Republic road. We had not left town an hour before the Yankee cavalry entered it. A little while after we left the pike I saw a Yankee cavalryman at the south end of Harrisonburg, sitting on his horse in the middle of the street, gazing about, making observations in a daring manner, and unconcernedly too prominent for his own or his country’s welfare. A Brock’s Gap rifleman was near me, and I saw that he was deeply interested in the Yankee’s bold deportment and conspicuous display of adventurous intrepidity. The rifleman watched him a while, and then I saw him take aim at the Yankee. When he fired I saw the Yankee’s horse walk leisurely away, and from all appearances the cavalryman had received a clear pass to that silent land from whose mystery-veiled fields no soldier e’er returns. It was a first-class shot, as the distance was about six hundred yards.

June 6 — Early this morning we left camp and passed through Harrisonburg, turning off of the Valley pike half a mile above town on the Port Republic road. We had not left town an hour before the Yankee cavalry entered it. A little while after we left the pike I saw a Yankee cavalryman at the south end of Harrisonburg, sitting on his horse in the middle of the street, gazing about, making observations in a daring manner, and unconcernedly too prominent for his own or his country’s welfare. A Brock’s Gap rifleman was near me, and I saw that he was deeply interested in the Yankee’s bold deportment and conspicuous display of adventurous intrepidity. The rifleman watched him a while, and then I saw him take aim at the Yankee. When he fired I saw the Yankee’s horse walk leisurely away, and from all appearances the cavalryman had received a clear pass to that silent land from whose mystery-veiled fields no soldier e’er returns. It was a first-class shot, as the distance was about six hundred yards.

We moved out about a mile on the Port Republic road and put our battery into position on a high and commanding elevation, from where we had a good view of the country around Harrisonburg. There were twelve pieces of artillery on the hill, and as a support for the batteries the First Maryland Infantry was on our right in the woods. The Yanks did not advance on our position, and after holding it two hours we moved back about four miles toward Cross Keys. We were then suddenly halted by heavy skirmish firing only a few hundred yards from us. We were ordered to wheel in battery immediately, on a hill where two of Jackson’s batteries, a Baltimore battery and Rice’s Virginia, were already in position. We were in position not more than half an hour before we were ordered to move to the front, where all our cavalry were. When we arrived within two miles of the Valley pike we went into position on a hill and in the edge of a woods, from where we saw the Yankee cavalry and infantry advancing and maneuvering through the fields south of Harrisonburg.

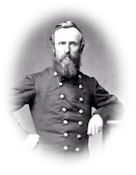

In the meantime General Ashby, with two regiments of infantry, the First Maryland and Fifty-Eighth Virginia, pushed through the woods on our right with the intention and object, I think, of checkmating the movement of a body of infantry that were thrown forward of their main army for the purpose of flanking and pressing our right.

It appears that Ashby’s object was to strike the body of infantry on the left flank and drive it back whence it came. It seems that the enemy contemplated Ashby’s movement, as they had already a line of infantry on their left posted along a fence hidden by a thicket at the edge of a woods, awaiting Ashby’s advance. The fence along which the enemy was posted was right in front of the field through which Ashby advanced. The field sloped gently to the east, which was a decided advantage to the enemy, as Ashby’s men had to approach their line over rising ground.

It seems that General Ashby was rather surprised to find the enemy in that particular locality, and it may have somewhat thwarted the original plan of his movement. However, as quick as he properly located the Yankee line he ordered up his infantry at a double-quick. When they arrived in the open field Ashby placed himself at the head of the Fifty-Eighth Virginia, with the First Maryland Regiment on his left. As they advanced across the field the Fifty-Eighth Virginia poured volley after volley into the thicket, that glowed with the shining musket barrels of the Pennsylvania Bucktails.

The fire of the Fifty-Eighth was promptly returned by the enemy all along the line behind the fence. For a while the musketry raged furiously, when the gallant Marylanders opened on the left with a well-directed and raking fire and advanced on the Yankee line.

The enemy fought stubbornly, and was difficult to dislodge from his position, but after the musketry roared for about an hour our men charged the line and drove the enemy into the woods, which ended the battle.

Ashby’s horse was shot from under him just before he ordered the charge. He then led the Fifty-Eighth on foot, and was in the thickest of the fight when he called on the Fifty-Eighth to charge, and as he was defiantly flourishing his saber at the Yankee line he was shot through the breast, and expired on the field immediately after. Thus fell the noble, brave, and gallant Ashby in the fore-front of battle, and the last command he gave was, “Virginians, Charge.”

When the infantry opened, which was done without many preliminary remarks in the way of skirmishing or sharpshooting, a body of Yankee cavalry debouched from a woods about a mile from our position. We opened on them with our rifled pieces, and as our percussion shell exploded in the midst of them it got too hot for the Yanks. They scattered and slunk back into the woods. Then we advanced and fired on their infantry until it was too dark to see where our shell anchored. We remained in battery for some time after we ceased firing, to see if the Yanks had anything else to try in the way of experimenting in the dark. Our position was in a low field which was thickly covered with rye nearly as high as our heads. A while after nightfall a line of Yankee sharpshooters fired in our direction, and I heard the bullets clipping through the rye like frightened grasshoppers. I have no idea what they were shooting at, as it was certainly too dark to see us in the rye, yet their bullets landed right in our neighborhood.

In the infantry fight where Ashby was killed there was no artillery engaged on either side. We were in position about half a mile to the left of the field where Ashby fell. The battle was fought late in the afternoon, and General Ashby was killed just before sunset, and the fighting ceased soon after he fell.

It was some time after dark when we left our last position, and as we were falling back a column of Ashby’s cavalry was slowly passing along a winding road through a dark woods, singing with rather feeling tones, with subdued voices,

….

“He sleeps his last sleep,

He has fought his last battle,

No sound can awake him to glory again.”

…

We had not heard then that our noble Ashby had fallen in the fray, but the ominous words of the song foretold that some brave spirit of the brigade had passed over the path of glory that leads to the grave, for the pathos of the voices engaged in singing evidently evinced that unbidden tears were stealing over cheeks of warriors who never wept in battle.

When it flashed over us that it was our beloved, generous, and brave leader, Ashby, who was sleeping his last sleep, the gloomy shadows of the night at once grew deeper, darker, and blacker, and the sable of grief hung like a slumbering pall over the whole command.

Ashby is gone. He has passed the picket line that is posted along the silent river, and the genius of science, the ingenuity of man, earth, and mortality combined cannot invent a countersign that will permit him to return. He is tenting to-night on the eternal camping-ground that lies beyond the mist that hangs over the River of Death, where no more harsh reveilles will disturb his peaceful rest nor sounding charge summon him to the deadly combat again.

To-day the South lost a true, courageous, and fearless champion of the cause when Ashby fell, and Virginia a worthy and noble son who fell with his face to the foe and his sword unsheathed, who poured out his blood in watchfully defending her homes and firesides against the encroachment of a hostile invader. And we as members of his command deeply feel the irreparable loss of an affable and generous leader and a brave and valiant commander. But his spirit still broods over us and its silent but cogent inspiration will always actuate us to avenge his death by valorous deeds in standing bravely and fearlessly in the fiery surge of battle’s deadly tide, sturdily fighting and daringly facing danger and even death for the home of the brave and the cause that our leader loved so well.

This afternoon by a little shrewd strategy and daring adventure General Ashby with a mere squad of men had captured Sir Percy Wyndham, an English officer, a real live Britisher, a colonel in the Yankee army, fighting for buncombe. A few hours afterwards, when Ashby passed us going to the front to lead the infantry, we wanted to cheer him for capturing a live Englishman from Great Britain. But Ashby surmised our intentions, and said, “Boys, don’t cheer me.” They were the last words I heard him speak. We are camped to-night about midway between Harrisonburg and Port Republic.