JUNE 23D.—And Gen. Johnston, I learn, has had his day. And Magruder is on “sick leave.” He is too open in his censures of the late Secretary of War. But Gen. Huger comes off scot-free; he has always had the confidence of Mr. Benjamin, and used to send the flag of truce to Fortress Monroe as often as could be desired.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Monday, 23d—Nothing of importance. I went out to the branch a mile from camp to do my washing. Burtis Rumsey of our company has been sick for about two weeks and he begged me to take two of his shirts along and wash them for him, so I did. I used a small camp kettle which the company cook has set aside for boiling clothes. Some of the boys in the company hire colored women to wash their clothes. I prefer to do my own washing.

23rd. Monday. According to orders started for Neosho at 6 A. M. Up early and flew around to get chores done. Our road lay mostly through the woods. After 8 miles ride, mail came. A letter from good Fannie. Met Co. “A” and “D” from Sherwood, three miles north of Neosho. Met some Kansas Sixth who had fallen in with a band of 400 rebels on the road to Granby. Council of War—Burnett wanting to go on with 200 men—Ratcliff not thinking it best. Bivouacked for the night in open air.

Written from the Sea islands of South Carolina.

[Diary] June 23, Monday.

General Hunter drove us out to the camp of the black regiment, which he reviewed. After our return I saw Mr. McKim and Lucy off, the steamer being crowded with the wounded and sick from the battle of Edisto. Then Mr. French advised my returning to General Hunter’s. Mrs. H. had asked me to stay all night, but I had declined. Now, however, it was too late to go back to Beaufort in the little steamer and there was no other chance but a sail-boat, so after waiting and hesitating a long time, I consented to the intrusion, and Mr. French escorted me back again, explaining to General and Mrs. Hunter my predicament. They were cordial in their invitation, and I had a long talk with them about plantation matters, sitting on their piazza, the sentry marching to and fro and members of the staff occasionally favoring us with their company.

The regiment is General Hunter’s great pride. They looked splendidly, and the great mass of blackness, animated with a soul and armed so keenly, was very impressive. They did credit to their commander.

As we drove into the camp I pointed out a heap of rotting cotton-seed. “That will cause sickness,” I said. “I ordered it removed,” he said, very quickly, “and why hasn’t it been done?” He spoke to the surgeon about it as soon as we reached Drayton’s house, which is just beside the camp. The men seemed to welcome General Hunter and to be fond of him. The camp was in beautiful order.

(This month was the one in which commenced the retreat, or “change of base,”) from before Richmond. The constant call on my time, from the last date to the 25th, prevented my keeping a full journal of events, and I therefore state, generally, that after having been compelled, for three weeks, to witness an amount of unnecessary suffering, which I cannot now contemplate without a shudder, I at last succeeded, by the efficient and cordial aid of my Assistant Surgeons, Dickinson, Tuttle, Freeman and Brett, (the last two named coming in at a late date) and by my ” insufferably insolent demands” on my superior officers, in getting the hospital well supplied with provisions, stores, bedding, &c. The Assistant Surgeons named above, have my acknowledgements and my grateful thanks for their ever willing and well-timed support of me in my efforts to relieve the sufferings of brave men under our care. I wish, too, to make my acknowledgement to Medical Director Brown, for his courteous and cordial support of my efforts. Nor can I pass here without bearing testimony to the ever-ready and humane efforts of the Sanitary Commission to aid, by every means in its power, in the proper distribution of comforts for the sick and wounded. On arriving at Washington, shortly after entering the service of the United States, I became much prejudiced by statements made to me against this organization, but it required but a short time to satisfy me that my prejudices were groundless. I have uniformly found the members both courteous and humane, and am satisfied that the privations of the soldiers would have been incomparably greater but for the aid received through them. From this Commission we received, about the 15th June, amongst other things, a generous supply of bed sacks. These, by the aid of the convalescents in hospital, were filled with the fine boughs of the cedar, pine and other evergreens, which made very comfortable beds, and in a few days after this every man was comfortably bedded and between clean, white sheets.[1] About the time of this change in the condition of the hospital, patients unable to be moved to the rear began to be sent in here from other hospitals. The removing of convalescents to the rear, and the breaking up numbers of hospitals and massing their very sick in one general field hospital, always indicates some active army operations. ‘Twas so in this case. But the condition of the patients sent in was shocking in the extreme, and a disgrace to the officers by whom such things are permitted. Poor fellows, wounded in battle, had been neglected till their wounded limbs or bodies had become a living mass of maggots. Legs were dropping off from rottenness, and yet these poor men were alive. Yet if the Surgeons had have protested against these things, perhaps they would have been threatened, as I was, with dismissal, and have been told that it was ” bad enough that this should be, without having it told to discourage the army.” There is no necessity for it, and the Surgeon who will submit to being made the instrument of such imposition on the soldiers, without a protest, deserves dismissal and dishonor. I must be permitted to insert here my most solemn protest against the action of any Governor, in promoting, at the request of (7×9) party politicians, (and in defiance of the remonstrance of those acquainted with the facts,) officers, and particularly surgeons, whose only notoriety consists in their ability to stand up under the greatest amount of whisky; and also against their re-appointing surgeons under the same influence who, after examination, have been mustered out of the service for incompetency. Under such appointments humanity is shocked, and a true and zealous army of patriots dwindle rapidly into a mass of mal-contents.

[1] A little incident here. Amongst the loads of hospital supplies furnished by the U. S. Sanitary Commission, were many articles of clothing and bedding marked with the names of the persons by whom they were donated. After the new beds were all made and severally assigned to those who were to occupy them, I was supporting a poor, feeble Pennsylvanian to his bed. As he was in the act of getting in he started back with a shriek and a shudder, accompanied by convulsive sobs so heart-rending that there was scarcely a dry eye in the ward. He stood fixed, staring and pointing at the bed, as if some monster was there concealed. As soon as he became sufficiently calm to speak, I asked what was the matter? With a half-maniacal screech he exclaimed—his finger still pointing—” My mother!” Her name was marked upon the sheet. Three days after the poor fellow died with that name firmly grasped in his hand. The sheet was rolled around him, the name still grasped, and this loved testimonial of the mother’s affection was committed with him to his last resting place. This circumstance was published at the time, in a letter from myself and I have seen it also stated in several papers, extracted from letters written to friends by soldiers in the hospital.

Eliza Woolsey Howland’s Journal.

Wilson Small, June 23.

A very anxious day. An orderly from Brigade Headquarters brought word from Captain Hopkins that Joe was ill and unable to write. I at once put up a basket of stores for him—bedsack, pillows, sheets, arrowroot, etc., etc., to go by the orderly, and Charley telegraphed Generals Slocum and Franklin to know the truth, while Mr. Olmsted arranged with Captain Sawtelle for a pass to take me to the front to-morrow morning. My mind was relieved, however, by the telegraphic answers and better accounts, and I have given up the idea of going out.

Saturday, 23d.—Feel some better this morning. Brother J. H. Magill came up from Mouse Creek to see me to-day. In afternoon, regiment passed through Knoxville, and Brother Tom is sent to this hospital, sick. J. H. got him in the same room with me. Got two letters to-day; one from Cousin Fannie Lowry, the other from 3, 3, 1.

(Note: picture is of an unidentified Confederate soldier.)

June 23—Moved our camp two miles up the road toward Richmond. It is a very bad camp—low ground and muddy. But there is a factory here, and plenty of girls to make up for the damp ground.

June 23d. Hot during the day, nothing important to note. In the course of the night it rained and blew terrifically. I was awakened by the tent blowing down on top of me and was obliged to crawl out and run to the guard house for assistance. Puffy, the quartermaster, who tents with me crawled out too, on the other side, swearing like a Dutch trooper. After a considerable struggle we succeeded in getting it up again and making the pegs hold; the difficulty is the ground is all sand and when it rains hard the pegs will not hold, and, consequently, the tent must come down. We got a famous bath by the operation.

June 23.—The London Times, of this date, said that whatever might be the result of the civil war in America, it was plain that it had reached a point at which it was a scandal to humanity. It had become a war of extermination. Utter destruction might be possible, or even imminent, but submission was as far off as ever. Persons who listened to the excited railers on either side might think that there was no alternative but to let a flood of blood pass over the land; but, at that calm distance, it might perhaps be wisely calculated that such voices did not represent the mind of the American people. Both parties ought by this time to be tired of the strife. There had been blood enough shed, fortunes enough made, losses enough suffered, and wrongs enough inflicted and endured. The opportunity ought to be either present or at hand when some potent American voice, prudently calling, “Peace,” might awaken an universal echo.

—Martial law was proclaimed in the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth, Va., by order of Brig. General E. L. Viele, Military Governor.

— Brigadier- General Schofield, Military Commandant District of Missouri, this day issued a General Order from his headquarters, St Louis, warning the rebels and rebel sympathizers in Missouri that he would hold them responsible in their property and persons for any damages that might thereafter be committed by the lawless bands of armed men which they had brought into existence, subsisted, encouraged, and sustained up to that time.

—The Third battalion, Fifth Pennsylvania cavalry. Col. Campbell, stationed at Gloucester Point, made a reconnoissance under the command of Major Wilson, into the counties of Gloucester and Mathews, Va., for the purpose of capturing a body of rebel cavalry, who were overrunning those counties, arresting deserters, and impressing others into their service who were unwilling to volunteer.

On arriving at Mathews’s Court-House, Major Wilson found he was a day too late. The rebel cavalry had been there, and arrested twenty-four men as being deserters from their army.

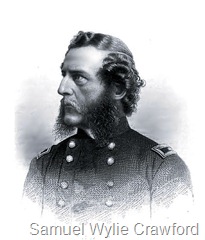

Samuel Wylie Crawford (Wikipedia) was the surgeon on duty at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, during the Confederate bombardment in 1861, which represented the start of the Civil War. Despite his purely medical background, he was in command of several of the artillery pieces returning fire from the fort.

A month after Fort Sumter, Crawford decided on a fundamental career change and accepted a commission as a major in the 13th U.S. Infantry. He served as Assistant Inspector General of the Department of the Ohio starting in September 1861. He was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers on April 25, 1862, and led a brigade in the Department of the Shenandoah, participating in the Valley Campaign against Stonewall Jackson, but the brigade saw no actual combat.