JUNE 25TH.—The people of Louisiana are protesting strongly against permitting Gen. Lovell to remain in command in that State, since the fall of New Orleans (which I omitted to note in regular order in these chronicles), and they attribute that disgraceful event, some to his incompetency, and others to treason. These remonstrances come from such influential parties, I think the President must listen to them. Yes, a Massachusetts man (they say Gen. L. came froth Boston) was in command of the troops of New Orleans when that great city surrendered without firing a gun. And this is one of the Northern generals who came over to our side after the battle of Manassas.

Monday, June 25, 2012

Wednesday, 25th—The weather is very hot today and our camp is becoming very dry and dusty. Twenty-seven men were detailed this morning to clean up our camp for general inspection.

Ditto, Ditto, June 25, 1862. Wednesday. — Dined with General Cox. He has a plan of operations for the Government forces which I like: To hold the railroad from Memphis through Huntsville, Chattanooga, Knoxville [and] southwest Virginia to Richmond; not attempt movements south of this except by water until after the hot and sickly season. This line is distant from the enemy’s base of supplies; can therefore by activity be defended, and gives us a good base.

June 25th. Issued the remainder of the ten days’ rations taken along. Received a letter from home.

Headquarters ist Division,

Battery Island, June 25th, 1862.

My dear Mother:

I have received your kind letters with their urgent requests from both you and Lilly to be present at the great affair which is to take place in July. How I would like to be there you can well divine, yet the fates never seem to favor my leaving my post. With all quiet in Beaufort I had my hopes; with all in turmoil here my chances seem but small, and yet there are some who have not been half the time in the service I have, who have visited their homes once, twice, and are now going home again. That is a sort of luck some people have, a sort of luck which does not favor me. Yet there will be a time, I suppose, when it will be pleasant to remember I was never absent from duty, though I cannot see that strictness in such respects is held in any special honor now. You must tell Lilly I will think of her with all a brother’s feeling of love when the day comes. I will see that I am properly represented at the table which bears her marriage gifts. I will dream of the orange flowers that bind the brow of the bride and will wish them — the bride and groom— God speed. I will wish them a brave career, and will rejoice that they do not fear to face the future together. I have no patience with that excessive prudence which would barter the blessings of youth and happiness and love for some silly hope of wealth, and the happiness wealth can give to hearts seared with selfishness and avarice. If misfortunes come, will they be heavier when borne together? And are men less likely to prosper when they have something more than themselves for which to toil? And when one man and one woman are brave enough to show they have no fear, but are willing to trust, “Bravo!” say I, “and God grant them all that they deserve.”

My coat and pants have come. All very well, only the coat is about six inches bigger round the waist than I am. There are tailors around the camp, though, who can remedy so excellent though rather ungraceful a fault.

I have had a letter from Hall lately, who seems quite happy. On this island, dear Mother, there are secret, hidden, insidious foes which undermine one’s happiness. We are truly in the midst of enemies which give no quarter, whose ruthless tastes blood alone can satisfy. Now I am not alluding to the human “Seceshers” — they are only mortal — but the insect kingdom. What a taste they have for Union blood! Mosquito bars are useless. They form breaches, and pierce every obstruction imagination can invent, when they once scent Union blood. Flies march over one in heavy Battalions — whole pounds of them at a time. Mosquitoes go skirmishing about and strike at every exposed position. Sandflies make the blood flow copiously. Fleas form in Squadrons which go careering over one’s body leaving all havoc behind. Ticks get into one’s hair. Ants creep into one’s stockings. Grasshoppers jump over one’s face. You turn and brush your face. You writhe in agony. You quit a couch peopled with living horrors. You cry for mercy! — In vain. These critters are “Secesh.” They give no quarter. You rush wildly about. You look for the last ditch. Until utterly exhausted you sink into unrefreshing sleep. Then begins a wild scene of pillage. Millions of thirsty beings, longing for blood, drink out one’s life gluttonously. Enough! Why harass you with these dismal stories?

Benham has been sent home under arrest. The last thing he did on leaving Hilton Head was to lie. He doubtless has not discontinued the practice since.

My love to Mary and Lilly, the little boys (how I would like to see them), and all my dear friends. I have been several times with a flag of truce to the enemy, concerning our prisoners in their hands. In all these interviews I heard of Sam Lord. I wished to see him very much, but permission was not granted. I was allowed, however, to write him concerning Miss Alice Mintzing’s welfare. The Colonel of his Battalion — Lamar — was badly wounded in our late engagement. Genl. Stevens has mentioned me handsomely in his official report of the fight, but he has done the same to all his staff-.

Very affec’y, your Son,

Will.

25th.—All in the hospital having been made comfortable, we set to work yesterday to take care of ourselves. Arranged our tents, and to-day find ourselves a band of contented Surgeons, assistants and nurses, willing now to remain where we are. The above lines were written at noon, and before the ink dried, an orderly rode up with a note, the first line of which read: “Surgeon, you will report for duty with your regiment, without delay.” So the fat of my content is all in the fire. I suppose there is another hospital to be organized. This constant change from newly established order and organization, to unorganized, chaotic confusion, is very trying. To establish a large field hospital, provision it and put it in good condition for the comfort of sick and wounded, in the short time allowed and with the disentangling of the red tape, is a big work, which I have been so frequently called on to perform, that I am heartily sick of it. No sooner do I get all comfortable, and become interested in the men under my care, than we must separate, perhaps, never to meet again.

On receipt of order to join my regiment, immediately mounted my horse in obedience, leaving behind me my tent, trunk, books, mess chest—everything but a case of surgical instruments, and reported at headquarters on the Richmond side of the Chickahominy. Found all quiet on the surface, but there was underneath a strange working of the war elements, which I could not comprehend. Officers spoke to each other in whispers—there was a trepidation in everything. There was “something in the wind.” But it blew no definite intelligence to me. I received no order for duty; only to hold myself in readiness for whatever might be assigned me.

Eliza Woolsey Howland’s Journal.

. . . June 25th. General Van Vliet says that if I want to go to the front at any time and will send him word, he will have his wagon meet me and take me over to J’s camp. This morning Dr. Bigelow came back to our boat from the front.

June 25—Reported fighting near Richmond.

“All the forts and redoubts belched forth their murderous fire over the heads of the advancing columns…” –Diary of Josiah Marshall Favill.

June 25th. The wind blew terrifically all day long. Early detailed six companies for picket duty. Shortly after they left camp the firing along the lines grew fast and furious, and at eight o’clock, we, with the other regiments of the brigade, were ordered to Seven Pines, to man the works in front of Heintzleman’s corps. We took position on the site of the original camp of Casey’s division, now transformed into a formidable fortress. Heintzleman moved forward through a heavy piece of timber to a clearing in front and met with determined opposition. All the forts and redoubts belched forth their murderous fire over the heads of the advancing columns, and thus assisted, they drove the enemy before them and got within four miles of Richmond. If they had remained there, and we had all marched forward, it would have amounted to something, but towards evening the whole force returned, and reoccupied their works, and we returned to our own camp. There was an immense expenditure of powder and shot, but little good resulted from it.

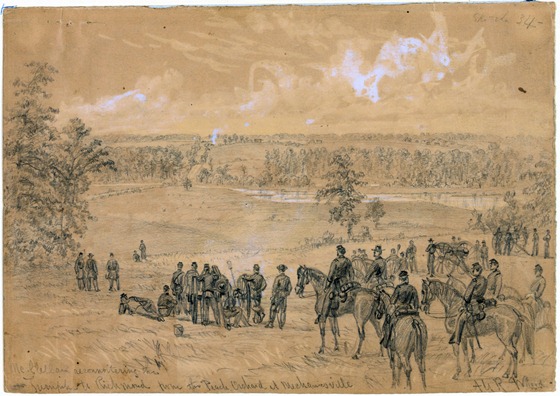

From Library of Congress:

1862 ca. June 25 – July 1

Signed lower right: Alf R. Waud. Title inscribed below image

1 drawing on light brown paper : pencil and Chinese white ; 18.3 x 26.0 cm. (sheet).

Part of Morgan collection of Civil War drawings. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Record page for this image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660821/