Camp Oliver.

June 6. We are now in a neatly arranged camp on somewhat elevated ground at the west side of the city, and about a quarter of a mile to the rear of Fort Totten, a large field fortification mounting twenty heavy guns. A back street runs along the left flank, on which is situated the guard quarters, and a line of sentinels extends along it. This camp is named Camp Oliver, in honor of Gen. Oliver of Salem, Mass., formerly adjutant general of that state. We can now brush ourselves up and settle down to the dull routine of camp life—Drills, parades, reviews, inspections, guard duty, fatigue duty and all manner of things which come under the head of a well ordered camp. Our two companies left at Red house are drawn in about five miles, and are now at the Jackson place on the Trent road. That brings them within easy distance. They can be easily reinforced in case of attack or make their own way back to camp. The Red house is again in the enemy’s country, but Mr. Bogey is not there; he thought he had rather live under the old flag and take his chances, and so moved with us into town.

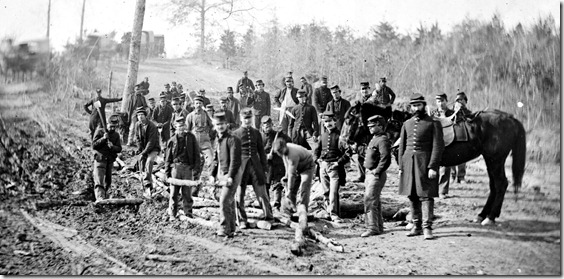

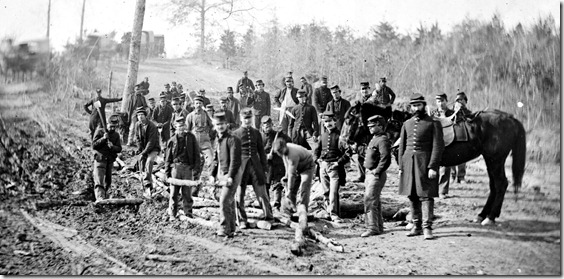

Title: Richmond, Va., vicinity. Engineers building corduroy road.

June 1862

Photographer: David B. Woodbury

I cropped this image to frame the road crew tighter than the original, while still showing the wagons behind them.

June 6th. The regiment moved forward to-day, over the large field we bivouacked on the night before the battle, and went into position on the very spot where the Texas rangers started their fires, which astonished us so much the night of our arrival. Have not removed our clothes, or accoutrements since the thirtieth day of May; the men sleep fully equipped, with arms by their side, ready for instant action; twice last night we turned out, and stood under arms for over an hour; picket firing heavy, with an occasional fort joining in the racket.

Georgeanna Woolsey to her mother.

June 6, Wilson Small.

We have on our boats nine “contraband” women from the Lee estate, real Virginia darkeys but excellent workers, who all “wish on their souls and bodies that the rebels could be put in a house together and burned up.” “Mary Susan,” the blackest of them, yielded at once to the allurements of freedom and fashion, and begged Mr. Knapp to take a little commission for her when he went to Washington. “I wants you for to get me, sah, if you please, a lawn dress, and a hoop skirt, sah.” The slave women do the hospital washing in their cabins on the Lee estate, and I have been up to-day to hurry them with the Knickerbocker’s eleven hundred pieces. The negro quarters are decent little houses with a wide road between them and the bank, which slopes to the river. Any number of little darkey babies are rushing about and tipping into the wash-tubs. In one cabin we found two absurdly small ones, taken care of by an antique bronze calling itself grandmother. Babies had the measles which would not “come out” on one of them, so she had laid him tenderly in the open clay oven, and with hot sage tea and an unusually large brick put to his morsels of feet, was proceeding to develop the disease. Two of the colored women and their husbands work for us at the tent kitchen. The other night they collected all their friends behind the tent and commenced in a monotonous recitative, a condensed story of the creation of the world, one giving out a line and the others joining in, from Genesis to the Revelation, followed with a confession of sin, and exhortation to do better ; till—suddenly—their deep humility seemed to strike them as uncalled for, and they rose at once to the assurance of the saints, and each one instructed her neighbor at the top of her voice to

“Go tell all de holy angels

I done, done all I kin.”

Just as they came to a pause, the train from the front with wounded arrived—midnight, and the work of feeding and caring for the sick began again. Dr. Ware was busy seeing that the men were properly lifted from the platform cars and put into our Sibley tents. Haight was “processing” his detail with blankets, and our Zouave and five men were going the rounds with hot tea and fresh bread, while we were getting beef tea and punch ready for the sickest through the night. By two o’clock we could cross the plank to our own staterooms on the Wilson Small.

June 6. [Okolona, Mississippi]—The enemy are still in Corinth, and are fortifying it. They do not seem inclined to follow us.

I have just received a letter from my brother, who is in camp near Baldwin.

June 6th.—Paul Hayne, the poet, has taken rooms here. My husband came and offered to buy me a pair of horses. He says I need more exercise in the open air. “Come, now, are you providing me with the means of a rapid retreat?” said I. “I am pretty badly equipped for marching.”

June 6th.—Paul Hayne, the poet, has taken rooms here. My husband came and offered to buy me a pair of horses. He says I need more exercise in the open air. “Come, now, are you providing me with the means of a rapid retreat?” said I. “I am pretty badly equipped for marching.”

Mrs. Rose Greenhow is in Richmond. One-half of the ungrateful Confederates say Seward sent her. My husband says the Confederacy owes her a debt it can never pay. She warned them at Manassas, and so they got Joe Johnston and his Paladins to appear upon the stage in the very nick of time. In Washington they said Lord Napier left her a legacy to the British Legation, which accepted the gift, unlike the British nation, who would not accept Emma Hamilton and her daughter, Horatia, though they were willed to the nation by Lord Nelson.

Mem Cohen, fresh from the hospital where she went with a beautiful Jewish friend. Rachel, as we will call her (be it her name or no), was put to feed a very weak patient. Mem noticed what a handsome fellow he was and how quiet and clean. She fancied by those tokens that he was a gentleman. In performance of her duties, the lovely young nurse leaned kindly over him and held the cup to his lips. When that ceremony was over and she had wiped his mouth, to her horror she felt a pair of by no means weak arms around her neck and a kiss upon her lips, which she thought strong, indeed. She did not say a word; she made no complaint. She slipped away fron the hospital, and hereafter in her hospital work will minister at long range, no matter how weak and weary, sick and sore, the patient may be. “And,” said Mem, “I thought he was a gentleman.” “Well, a gentleman is a man, after all, and she ought not to have put those red lips of hers so near.”

June 6.—At five o’clock A.m., the United States fleet in the Mississippi river, near Memphis, engaged the rebel fleet of eight rams and gunboats, and after a two hours’ fight, seven of the rebel craft were either captured or destroyed. On the conclusion of the battle, the Mayor of Memphis surrendered the city.—(Doc. 60.)

—Gen. Fremont’s army reached Harrisonburgh, Va., at two o’clock this afternoon, and drove out the rebel rear-guard from the town. At four o’clock the First New-Jersey cavalry, after driving the enemy through the village, fell into an ambuscade, and Colonel Windham, its commander, was captured. The regiment sustained considerable loss. General Bayard subsequently engaged the rebels with his brigade, drove them from his position, capturing their camp. They then continued their retreat—(Doc. 63.)

—The tax bill was passed by the Senate of the United States, by a vote of thirty-seven to one, Mr. Powell, of Kentucky, voting in the negative.

June 6th.—Paul Hayne, the poet, has taken rooms here. My husband came and offered to buy me a pair of horses. He says I need more exercise in the open air. “Come, now, are you providing me with the means of a rapid retreat?” said I. “I am pretty badly equipped for marching.”

June 6th.—Paul Hayne, the poet, has taken rooms here. My husband came and offered to buy me a pair of horses. He says I need more exercise in the open air. “Come, now, are you providing me with the means of a rapid retreat?” said I. “I am pretty badly equipped for marching.”