June 13th. There was much excitement just before daylight this morning, the rebels opening a tremendous cannonade on Sumner’s headquarters, creating a general stampede in that direction. All the troops fell in and remained in line, till the firing ceased; our big guns in the new redoubts and forts replied and made a terrific row. It was all wasted ammunition, I suppose; no losses on our side, at any rate. Weather very hot, so we sent to the woods for pine boughs, and had them placed in front of our tents; to keep the sun off. Seth made some fine seats of inverted cracker boxes, and we can now sit outside under the shade of the pines, and get the air. How many men are killed every day on the picket line, from the fire of the sharpshooters? It does no good, and has not the most remote effect upon the ultimate result, is barbarous, and ought to be stopped. Got a furlough for Quartermaster Sergeant Smith to-day, and made out field returns. In the evening we lay under our fine shade trees, and sampled some Rhine wine brought up by the sutler; found it good; got hold of a Richmond paper to-day, containing an account of the fight of the thirty-first and first, from the rebel point of view. They admit there was great confusion on the night of the first, and that they fully expected us to follow them up. It was a serious mistake we did not do so; they must have been demoralized by the great change in affairs on the first; on the thirty-first they had considerable success, capturing Casey’s camp and stores, two or three batteries, and drove back all the reserves brought up to oppose them, until night stopped the fighting. The following morning everything was reversed; they lost all they had gained the previous day, leaving their camp equipage and dead and wounded in our hands, and lost heavily all along the line; nothing prevented a great disaster to the Confederacy on the first but the timidity of McClellan; officers and men were ready and anxious to advance, and would, if allowed to have done so, followed the enemy directly into their works. Colonel Bailey, the chief of artillery of Key’s corps, was killed on the first. I knew him when he first joined the army, after graduating from West Point. He was a splendid specimen of the genus homo, and married to one of the most beautiful women I ever saw, one of Major Patten’s daughters, of Fort Ontario, Oswego. He was a fine officer, and his death is a great loss to the service.

June 13th. There was much excitement just before daylight this morning, the rebels opening a tremendous cannonade on Sumner’s headquarters, creating a general stampede in that direction. All the troops fell in and remained in line, till the firing ceased; our big guns in the new redoubts and forts replied and made a terrific row. It was all wasted ammunition, I suppose; no losses on our side, at any rate. Weather very hot, so we sent to the woods for pine boughs, and had them placed in front of our tents; to keep the sun off. Seth made some fine seats of inverted cracker boxes, and we can now sit outside under the shade of the pines, and get the air. How many men are killed every day on the picket line, from the fire of the sharpshooters? It does no good, and has not the most remote effect upon the ultimate result, is barbarous, and ought to be stopped. Got a furlough for Quartermaster Sergeant Smith to-day, and made out field returns. In the evening we lay under our fine shade trees, and sampled some Rhine wine brought up by the sutler; found it good; got hold of a Richmond paper to-day, containing an account of the fight of the thirty-first and first, from the rebel point of view. They admit there was great confusion on the night of the first, and that they fully expected us to follow them up. It was a serious mistake we did not do so; they must have been demoralized by the great change in affairs on the first; on the thirty-first they had considerable success, capturing Casey’s camp and stores, two or three batteries, and drove back all the reserves brought up to oppose them, until night stopped the fighting. The following morning everything was reversed; they lost all they had gained the previous day, leaving their camp equipage and dead and wounded in our hands, and lost heavily all along the line; nothing prevented a great disaster to the Confederacy on the first but the timidity of McClellan; officers and men were ready and anxious to advance, and would, if allowed to have done so, followed the enemy directly into their works. Colonel Bailey, the chief of artillery of Key’s corps, was killed on the first. I knew him when he first joined the army, after graduating from West Point. He was a splendid specimen of the genus homo, and married to one of the most beautiful women I ever saw, one of Major Patten’s daughters, of Fort Ontario, Oswego. He was a fine officer, and his death is a great loss to the service.

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

While we were lying at White House in the Wilson Small, one day, Mr. Olmsted came to G. with the statement that “young Mr. Mitchell of New York, who had come down to help in the Commission’s Quarter-master’s department, was ill on the supply boat Elizabeth.” G. went across the plank to him at once, and found a most attractive six or seven feet of future brother-in-law cramped into an uncomfortable little hole of a cabin. This was E. M.’s first introduction to the family; he was looked after a little, and sent home in a returning hospital ship to recruit. Mr. Olmsted had his father’s private instructions to keep him out of the army.

Abby Howland Woolsey a little later, writes:

Abby Howland Woolsey a little later, writes:

Mr. Mitchell called yesterday afternoon to say good-bye and to offer to take anything to Georgy. Dr. Agnew had sent for him in a great hurry to go back as quartermaster on the Elm City. He had promised to go back on three or four days’ notice, and had hoped to spend those at the seaside, where his physician had told him he ought to go. We had nothing for Georgy, the Elm City lying at Jersey City, it would not have been convenient anyhow—but Carry took to his house in 9th street a letter to Georgy and a large bundle of candy for himself.—(C’s first present to her future husband).

June 13th.—Decca’s wedding. It took place last year. We were all lying on the bed or sofas taking it coolly as to undress. Mrs. Singleton had the floor. They were engaged before they went up to Charlottesville; Alexander was on Gregg’s staff, and Gregg was not hard on him; Decca was the worst in love girl she ever saw. “Letters came while we were at the hospital, from Alex, urging her to let him marry her at once. In war times human events, life especially, are very uncertain.

“For several days consecutively she cried without ceasing, and then she consented. The rooms at the hospital were all crowded. Decca and I slept together in the same room. It was arranged by letter that the marriage should take place; a luncheon at her grandfather Minor’s, and then she was to depart with Alex for a few days at Richmond. That was to be their brief slice of honeymoon.

“The day came. The wedding-breakfast was ready, so was the bride in all her bridal array; but no Alex, no bridegroom. Alas! such is the uncertainty of a soldier’s life. The bride said nothing, but she wept like a water-nymph. At dinner she plucked up heart, and at my earnest request was about to join us. And then the cry, ‘ The bridegroom cometh.’ He brought his best man and other friends. We had a jolly dinner. ‘Circumstances over which he had no control’ had kept him away.

“His father sat next to Decca and talked to her all the time as if she had been already married. It was a piece of absent-mindedness on his part, pure and simple, but it was very trying, and the girl had had much to stand that morning, you can well understand. Immediately after dinner the belated bridegroom proposed a walk; so they went for a brief stroll up the mountain. Decca, upon her return, said to me: ‘Send for Robert Barnwell. I mean to be married to-day.’

“‘Impossible. No spare room in the house. No getting away from here; the trains all gone. Don’t you know this hospital place is crammed to the ceiling?’ ‘Alex says I promised to marry him to-day. It is not his fault; he could not come before.’ I shook my head. ‘I don’t care,’ said the positive little thing, ‘I promised Alex to marry him to-day and I will. Send for the Rev. Robert Barnwell.’ We found Robert after a world of trouble, and the bride, lovely in Swiss muslin, was married.

“Then I proposed they should take another walk, and I went to one of my sister nurses and begged her to take me in for the night, as I wished to resign my room to the young couple. At daylight next day they took the train for Richmond.” Such is the small allowance of honeymoon permitted in war time.

Beauregard’s telegram: he can not leave the army of the West. His health is bad. No doubt the sea breezes would restore him, but—he can not come now. Such a lovely name—Gustave Tautant Beauregard. But Jackson and Johnston and Smith and Jones will do—and Lee, how short and sweet.

“Every day,” says Mem, “they come here in shoals— men to say we can not hold Richmond, and we can not hold Charleston much longer. Wretches, beasts! Why do you come here? Why don’t you stay there and fight? Don’t you see that you own yourselves cowards by coming away in the very face of a battle ? If you are not liars as to the danger, you are cowards to run away from it.” Thus roars the practical Mem, growing more furious at each word. These Jeremiahs laugh. They think she means others, not the present company.

Tom Huger resigned his place in the United States Navy and came to us. The Iroquois was his ship in the old navy. They say, as he stood in the rigging, after he was shot in the leg, when his ship was leading the attack upon the Iroquois, his old crew in the Iroquois cheered him, and when his body was borne in, the Federals took off their caps in respect for his gallant conduct. When he was dying, Meta Huger said to him: “An officer wants to see you: he is one of the enemy.” “Let him come in; I have no enemies now.” But when he heard the man’s name:

“No, no. I do not want to see a Southern man who is now in Lincoln’s navy.” The officers of the United States Navy attended his funeral.

June 13.—This day a force of about three hundred rebel troops left Fort Chapman, and proceeded to Hutchinson Island, S. C, where they killed and wounded a number of negroes, and burned a chapel and dwelling-house. On the approach of the boats of the United States ship Dale, lying in St Helena Sound, the rebels retreated. About seventy negroes were taken on board the Dale, including several of the wounded.—(Doc. 69.)

—Colonel James R. Slack, commanding at Memphis, Tenn., issued the following order:

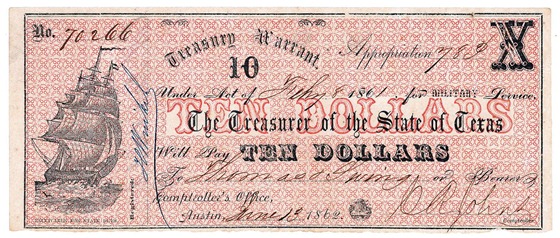

“Hereafter the dealing in and passage of currency known as ‘confederate scrip’ or ‘confederate notes’ is positively prohibited, and the use thereof as a circulating medium regarded as an insult to the Government of the United States, and an imposition upon the ignorant and deluded. “All persons offending against the provisions of this order will be promptly arrested and severely punished by the military authorities.”

— The Bank of Louisiana, at New-Orleans, being ordered by the Provost-Judge to pay a citizen in current funds his deposit formerly received by them in confederate notes, the Bank appealed to General Butler, who sustained the decision of the Judge.—Congress passed a joint resolution of thanks to Lieut. Morris and the other officers and men of the United States frigate Cumberland.

—The pickets of Gen. McClellan’s army near Richmond were driven in from Old Church, and large bodies of the rebels were discovered moving from the neighborhood of Mechanicsville bridge and Richmond towards the battle-field of Fair Oaks.—(Doc. 67.)

—At daylight this morning the rebels opened a sharp fire of artillery in front of Gen. Sumner’s position, in the vicinity of Richmond, which continued three hours, killing one and wounding another of the National troops.

—The United States flag was this day raised in the village of Gretna, La., amid the rejoicings of a large number of spectators. After the ceremony a series of patriotic resolutions were unanimously passed.

—The rebel transport Clara Dolsen was captured on the White River, Arkansas, by the tug Spitfire.—(Doc. 70.)

—A fight took place on James Island, S. C, between a body of Union troops and a much superior force of the rebels, resulting in the retreat of the rebels with a loss of nineteen killed and six wounded. The Union party lost three killed and nineteen wounded.—Official Report.

From Library of Congress:

Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s raid around McClellan, June 1862

copyright 1900, Jones Bros. Pub. Co.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Record page for this image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93504431/