June 16th. The rumor of a night attack proved utterly groundless, nothing out of the usual happened. We slept in our blankets in line of battle, and slept pretty well, too. When an alarm is sounded now, all hands rush to the color line, nobody waiting for orders. This makes it easier for me, and saves time. Food still poor for officers on account of the non-appearance of the sutlers. The men get fresh beef twice a week; bean soup, salt pork, dessicated vegetables, and occasionally canned peaches. In appearance, we are almost as dark as Indians, the regulation fatigue cap being the worst possible protection for the face. All the officers wear soldiers’ trousers and blouses, the latter simply ornamented with gilt buttons and shoulder straps. We buy these things from the quartermaster, paying cost price for them. Our full dress hat is the slouch soft hat, with gold cord and acorn tassles; gold wreath in front encircling for infantry, a bugle; artillery, crossed cannons; cavalry, crossed sabres; and staff and general officers, U. S. We have long ago done away with the gold sword knot, and now use a strong leather one, which is serviceable. Seth I find the greatest of all treasures. He is indefatigable in his attention to my comfort; and never neglects anything belonging to me; books, horses, swords, buckles, and clothes are always in order; and when I want to be amused, he is ever ready to talk interestingly upon a great variety of subjects, and knows when to stop and when to go ahead.

Saturday, June 16, 2012

“In appearance, we are almost as dark as Indians.”–No rebel night attack..–Diary of Josiah Marshall Favill.

BOOK II

“I hope to die shouting, the Lord will provide!”

Monday, June 16th, 1862.

There is no use in trying to break off journalizing, particularly in “these trying times.” It has become a necessity to me. I believe I should go off in a rapid decline if Butler took it in his head to prohibit that among other things. . . . I reserve to myself the privilege of writing my opinions, since I trouble no one with the expression of them. . . . I insist, that if the valor and chivalry of our men cannot save our country, I would rather have it conquered by a brave race than owe its liberty to the Billingsgate oratory and demonstrations of some of these “ladies.” If the women have the upper hand then, as they have now, I would not like to live in a country governed by such tongues. Do I consider the female who could spit in a gentleman’s face, merely because he wore United States buttons, as a fit associate for me? Lieutenant Biddle assured me he did not pass a street in New Orleans without being most grossly insulted by ladies. It was a friend of his into whose face a lady spit as he walked quietly by without looking at her. (Wonder if she did it to attract his attention?) He had the sense to apply to her husband and give him two minutes to apologize or die, and of course he chose the former.[1] Such things are enough to disgust any one. “Loud” women, what a contempt I have for you! How I despise your vulgarity!

Some of these Ultra-Secessionists, evidently very recently from “down East,” who think themselves obliged to “kick up their heels over the Bonny Blue Flag,” as Brother describes female patriotism, shriek out, “What! see those vile Northerners pass patiently! No true Southerner could see it without rage. I could kill them! I hate them with all my soul, the murderers, liars, thieves, rascals! You are no Southerner if you do not hate them as much as I!” Ah ça! a true-blue Yankee tell me that I, born and bred here, am no Southerner! I always think, “It is well for you, my friend, to save your credit, else you might be suspected by some people, though your violence is enough for me.” I always say, “You may do as you please; my brothers are fighting for me, and doing their duty, so that excess of patriotism is unnecessary for me, as my position is too well known to make any demonstrations requisite.”

This war has brought out wicked, malignant feelings that I did not believe could dwell in woman’s heart. I see some of the holiest eyes, so holy one would think the very spirit of charity lived in them, and all Christian meekness, go off in a mad tirade of abuse and say, with the holy eyes wondrously changed, “I hope God will send down plague, yellow fever, famine, on these vile Yankees, and that not one will escape death.” O, what unutterable horror that remark causes me as often as I hear it! I think of the many mothers, wives, and sisters who wait as anxiously, pray as fervently in their faraway homes for their dear ones, as we do here; I fancy them waiting day after day for the footsteps that will never come, growing more sad, lonely, and heart-broken as the days wear on; I think of how awful it would be if one would say, “Your brothers are dead”; how it would crush all life and happiness out of me; and I say, “God forgive these poor women! They know not what they say!” O women! into what loathsome violence you have abased your holy mission! God will punish us for our hard-heartedness. Not a square off, in the new theatre, lie more than a hundred sick soldiers. What woman has stretched out her hand to save them, to give them a cup of cold water? Where is the charity which should ignore nations and creeds, and administer help to the Indian and Heathen indifferently? Gone! All gone in Union versus Secession! That is what the American War has brought us. If I was independent, if I could work my own will without causing others to suffer for my deeds, I would not be poring over this stupid page; I would not be idly reading or sewing. I would put aside woman’s trash, take up woman’s duty, and I would stand by some forsaken man and bid him Godspeed as he closes his dying eyes. That is woman’s mission! and not Preaching and Politics. I say I would, yet here I sit! O for liberty! the liberty that dares do what conscience dictates, and scorns all smaller rules! If I could help these dying men! Yet it is as impossible as though I was a chained bear. I can’t put out my hand. I am threatened with Coventry because I sent a custard to a sick man who is in the army, and with the anathema of society because I said if I could possibly do anything for Mr. Biddle — at a distance — (he is sick) I would like to very much. Charlie thinks we have acted shockingly in helping Colonel McMillan, and that we will suffer for it when the Federals leave. I would like to see any man who dared harm my father’s daughter! But as he seems to think our conduct reflects on him, there is no alternative. Die, poor men, without a woman’s hand to close your eyes! We women are too patriotic to help you! I look eagerly on, cry in my soul, “I wish —”; you die; God judges me. Behold the woman who dares not risk private ties for God’s glory and her professed religion! Coward, helpless woman that I am! If I was free —!

[1] This passage was later annotated by Mrs. Dawson as follows: “Friend (Farragut). Lady (I know her, alas!). Husband (She had none!).”

June 16.—A few days ago Mrs. Thornton received news that her eldest son had been wounded in the late battle near Richmond. She is a good deal worried about him, but bears the news with fortitude. She is one who would think life a disgrace, received as the price of liberty. She is very hopeful as to his being well cared for, and is certain that some good woman is administering to his wants in that grand old patriotic state—Virginia. We hear much about the kindness of the people there to the sufferers.

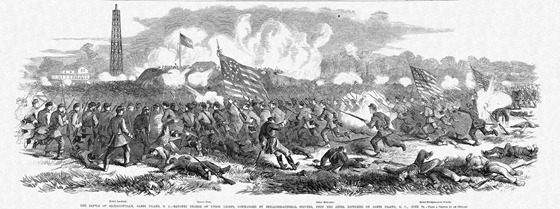

Bayonet Charge at Secessionville, SC, June 16, 1862 – Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

Click on image to view larger version.

The Battle of Secessionville.

(from The days of the Swamp Angel by Mary Hall Leonard, 1914)

Since the taking of Port Royal the United States had gradually gained possession of nearly all the Sea Islands south of Charleston, as the Confederates left them one by one. Now it was said at the War Department in Washington that if the Union forces were suddenly concentrated on James Island, and if Fort Johnson could be taken, the city itself might be reached by Federal batteries. So from Hilton Head the troops embarked, landing at Old Battery on the Stono River. But by this time the Confederates had erected the new fortification, afterward called Fort Lamar, to keep off the invaders. The commander of the Union forces now attempted by a sudden overwhelming movement to capture this fort.

On the morning of June 16 the people of Charleston were startled by the discharge of guns and by smoke in the direction of James Island. Messengers soon began to arrive in the city and telegrams from the nearest points came pouring in.

The whole town was in a tremor of excitement. People thronged the streets, watching the smoke of the battle, listening to the sounds of the firing, and eagerly asking one another for news.

Thus was precipitated the battle of James Island, or Secessionville, resulting in the repulse of the United States troops, who fell back, leaving their killed and wounded on the field.

With the retreat of the invaders a great wave of rejoicing swept over the community. But there was no time for idle exultation. The wounded must be cared for. Mourners must be comforted. Preparations must be made for further defense in case of renewed attack.

Frampton Place, near the scene of the battle, was at once made into a temporary hospital, though as soon as possible the wounded and the prisoners were brought into the city. The hospitals were filled with the injured of both armies, and many of the ladies of Charleston found a new field for service as volunteer nurses. As for Dr. MacPherson, he seemed to be in a dozen places at once, attending personally to the most important cases, and organizing and superintending the work of other surgeons.

To the relief of the Confederates, the Northern general did not renew the attack. The defeat at Secessionville terminated this invasion, and no more attempts were made to enter Charleston from the rear.

June 16.—The Richmond Dispatch of this date says: “Desertion has become far too frequent in the confederate army. And yet the habit is not peculiar to confederate soldiers. There must be desertions from all military service where there is no punishment for desertion. We mean no punishment adequate to the offence—none which a coward or vagabond had not rather encounter than endure the service or the perils of a battle. Death is the proper punishment, and it is the punishment prescribed in our laws—the punishment meted to the deserter by governments generally. We anticipate that our own government will be forced to resort to it. With a creditable humanity and forbearance, the policy of appealing to the pride of the soldier by advertisement, by disgraces, has been pursued by our commanders; but there is little pride and no honor in the deserter, and the fear of disgrace will not deter him from absconding. The penalty of death will. An example or two would have a fine effect.”

—The battle of Secessionville, James Island, S. C, was fought this day, resulting in the defeat of the National forces.—(Doc. 72.)

—Attorney-General Bates officially communicated to the Secretary of War his opinion concerning the relations of Governors of States to volunteers in the National service.—(See Supplement.)

—At Memphis, Tenn., a large body of rebel officers and soldiers, together with citizens of the city, took the oath of allegiance to the United States.—Memphis Avalanche, June 17.

—This day, while a few soldiers were hunting for deserters in the vicinity of Culpeper, Va., they suddenly came upon a rebel mail-carrier who was endeavoring to conceal himself in the woods. He was immediately arrested, after a slight resistance, and taken to headquarters at Manassas. A large number of letters to prominent officers in the rebel service, many of which contained valuable information, were found in the mail-bag, also ten thousand dollars in confederate bonds. The carrier’s name was Granville W. Kelly.—Baltimore American, June 18.

—Surgeon Hayes, One Hundred and Tenth regiment Pennsylvania volunteers, having been ordered to conduct to Washington a large detachment of sick and wounded men, and having shamefully neglected them after their arrival, the President directed that for this gross dereliction of duty he be dismissed the service, and he was accordingly dismissed.— General Order.

—This afternoon the rebels in front of the National pickets near Fair Oaks, Va., attempted to flank a portion of the Union forces during a violent thunder-storm, but were soon repulsed with some loss. Lieut. Palmer, Aid to Gen. Sickles, while giving orders to the commandant of the regiment attacked by the rebels, fell pierced with three balls.

—Four of the five men, who, while personating Union soldiers, entered and pillaged a house in New-Orleans, La., of a large sum of money and other valuables, were this day hanged in that city. The fifth man was reprieved.