June 27th. Contrary to expectations, the night was unusually quiet. We only fell in twice and remained in line less than hour, all told. At daybreak, however, a general fusilade opened all along the line, and the troops were kept under arms till seven o’clock. Then came a general lull, during which we got our breakfast. Heard from the right later on that Porter had been obliged to contract his lines and expected a renewal of the attack. What seems remarkable is that we are not sent over there to assist him in holding the position.

June 27th. Contrary to expectations, the night was unusually quiet. We only fell in twice and remained in line less than hour, all told. At daybreak, however, a general fusilade opened all along the line, and the troops were kept under arms till seven o’clock. Then came a general lull, during which we got our breakfast. Heard from the right later on that Porter had been obliged to contract his lines and expected a renewal of the attack. What seems remarkable is that we are not sent over there to assist him in holding the position.

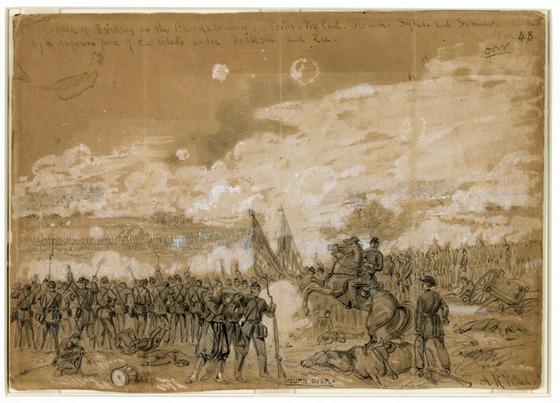

About 2 P. M. the enemy renewed the attack on Porter’s corps, while we stood under arms and watched the whole affair. This time no skirmish line commenced the fight, but immense lines of infantry, under cover of scores of guns, marched directly to the attack, followed by several other lines in succession. It was a fine sight for us, but as the rebel line of fire gradually advanced and ours retired, we grew nervous and wondered whether we were to stand by and see them thrashed, without being called to their assistance. Every little while a fusilade broke out on our front, but did not amount to much. Colonel Zook, who was field officer of the day, came in and reported most of the enemy’s force in front had disappeared. He crept out in advance of the picket line, and saw a whole lot of niggers parading, beating drums, and making a great noise; with true military instinct he concluded the enemy in front had gone to join in the attack on Porter and immediately rode in to General Sumner and demanded permission to lead an attack, asserting his ability to convince the general at once of the truth of his discovery. General Sumner was afraid to act on his own responsibility, but sent an aide to General McClellan to report the colonel’s conclusion, and that was the last we heard about the matter. Zook was greatly chagrined and amazed at the want of activity on Sumner’s part, feeling certain we could have got into Richmond or into the rear of Lee’s army. Nothing was done, however, to distract the rebels’ attention, and they were allowed to continue the fight with their whole army against our one corps. In the meantime, the battle progressed with great fury; the fighting was stubborn, our men falling back slowly and reluctantly, fighting every inch of the ground; the hills soon became entirely enveloped in thick smoke, the flashes only visible from the big guns, so we could only judge of the result by the sound of the musketry; this sufficiently indicated the gradual advance of the rebels and increased our anxiety. At three o’clock, Meagher’s Irish brigade, of our division, was ordered across to Porter’s assistance and a little later we received similar orders. We started immediately and marched directly for the pontoon bridge at the bend of the river; here there was some delay, waiting for orders. About six o’clock we crossed over and ascended the steep hill on the north side, which was crowded with a disorderly mass of wounded men and skulkers, all making their way to the rear. Rush’s regiment of lancers was riding furiously and aimlessly about the road, adding to the excitement. As the immediate rear of a battle is always a disorderly place, we did not think much of it and marched briskly forward to the heights above, and there formed in line of battle. Everything about us was in disorder; troops to right and left were hurrying away, and there was no doubt but that Porter’s corps was thrashed. After standing in line a while, we were ordered to move forward and select the best position we could find. There was no one to lead the way, and General French was not to be found, so we went ahead, passing a deserted field battery and a splendid siege battery, whose horses had been killed and the guns abandoned; at a loss what to do we moved down the side of the hill towards the rebels’ line, which was not, however, in sight, and finding a good ridge halted and lay down in a field of very tall grass. It was quite dusk by this time, and the action was over; the rebel batteries, however, fired at us with solid shot and made it slightly uncomfortable. The colonel threw out a skirmish line a short distance in front and directed me to ride back and find French and explain our position and get instructions. I rode back over the field now deserted, or occupied only by dead men and horses and abandoned guns, a most melancholy sight. I searched a long time without finding a solitary man; apparently, our brigade was alone in front, all the other troops having gone to the rear. I passed through an orchard, near which the siege guns were deserted, and after wandering about for some time, stumbled on General French, sitting beneath an apple tree, and told him where we were and asked for instruction. He said he did not know what was on our right or left, but that there must be somebody, and I must go back and try and make connections, if it had not already been done. He further directed Zook to hold the line at all hazards until relieved; then he added, confidentially, that he expected we should be withdrawn during the night, so there was no necessity for any particular formation. Billy was with the general, who was not very well. On my way back, I rode past the field hospital, where strewn around a house were hundreds and hundreds of wounded men, crying and groaning, while in the house, by the aid of candles and lamps, the surgeons were working away, stripped to their shirt sleeves. This time I passed many lines of troops, all marching to the rear, which satisfied me we were going to abandon the position before daylight. I had much trouble in finding the brigade, and as the enemy still sent their round shot skipping around the field, it was anything but a comfortable ride; finally, I came out in the right place and explained the situation to the colonel, who suspected what had happened. While we lay in the long grass, keeping a sharp lookout, Doctor Dean came straggling in from the front, with thirty men, who proved to belong to the Sixth Alabama regiment. He had strayed outside the picket line and ran into a squad of men who asked him where the Sixth Alabama lay. He told them to follow him, which they did, coming directly into our line. They were highly disgusted; not disguising their chagrin at being deceived and captured by a sawbones. We gained some knowledge of the rebel lines from these prisoners, which induced us to change ours somewhat on the left. No adventure of any kind occurred during the night. Just before daylight Billy came along and gave an order to withdraw and form the rear guard, Meagher’s brigade preceding us, and everything else in the shape of troops, guns, supplies, and ambulances. French rode up to us when we reached the large orchard, and told Colonel Zook we had been selected for continuous service as rear guard, on account of our reputation for discipline, and must be prepared for all contingencies. Porter’s corps had been withdrawn during the night, and I was rejoiced to find the abandoned siege battery I noticed last night conspicuous by its absence. I felt an extreme pleasure to think it was not to be left behind. All the badly wounded were to be abandoned. Surgeons have been detailed to remain behind and care for them. We hear over thirty guns have been abandoned, but hope this is not true. Just as we reached the brow of the hill descending to the river over which we advanced yesterday, an immense pile of stores of all kinds was set on fire, and in a few moments was a mass of flames. The enemy made no attempt to follow or interrupt our retreat, and by daybreak we were across the river and the bridge destroyed. Our brigade marched directly to their camp, struck tents, and loaded everything not absolutely necessary into the wagons; as soon as this was done the wagon train started off in the direction of Savage’s Station.

After the wagon train started, the regiment lay down on their arms to await further orders and the colonel and I rode over to our one place of general information, Sumner’s headquarters, where from Captain Taylor we are always sure to get all the information it is legitimate to give. He is a genial, pleasant gentleman and remembers us all familiarly since our Camp California experiences brought us so much together. We learned from him that Stuart’s cavalry and Early’s division of infantry had been making a grand raid around the rear of our army, tearing up railroads, destroying, and capturing stores; intercepting communications, and generally scaring everybody into fits. The result of this great raid is the determination of General McClellan to change his base from Pamunkey to the James river; and, hence, the refusal to support Porter and fight a great battle. In fact, we are to turn tail, without making any further effort to perform the duty we came here for, and under the respectable guise of a change of base are really to give up the effort to capture Richmond, at least for the time being. This is not all; we are to attempt a most difficult and dangerous operation, in which we must abandon all our dead and wounded, to say nothing of immense quantities of every kind of stores. It is certainly mortifying to contrast our present situation with what might have been, and what we had good reason to believe would have been, if we had a genius in command.

In order to get to the James, we must cross the White Oak swamp; a densely wooded morass, varying from one to two feet in water, passable only by two or three wood roads. There are many roads from Richmond intersecting the crossing, which will afford ample opportunity for the enemy to make himself felt, and in the course of events will no doubt play an important part in the retreat. Casey’s division, which was on duty at the White House, has gone by transport around to the James already, together with the whole fleet of transports, gunboats, floating hospitals, etc.; all the stores that could not be loaded into wagons have been destroyed.