Rienzi, Miss., Tuesday, Sept. 2. We went out in the morning to drill on the field but did not see much into the wild scampering way. I wrote to Sp[ring] Gr[een]. – Had no time to write home before mail went out. Was drilled on foot by Corporal Sweet in the evening.

Sunday, September 2, 2012

[The beginning of the next letter is lost, but I remember the circumstances which occasioned it. Colonel Webb, of McClellan’s staff, came up to see the Army, and he was invited to breakfast by Ruggles, who was on Pope’s staff. The rest explains itself.]

. . . Webb was quite hungry. Pretty soon he saw Pope call Ruggles aside and begin to scold at him. He thought from Pope’s manner that he was displeased at Ruggles asking him to breakfast, and so he took up his hat and bid them good morning. Ruggles came up to him and said: “The truth is, Webb, that General Pope don’t like my asking you to breakfast. He says that he won’t have any of General McClellan’s staff at his table.”Pretty small for Pope.

There is a rumor that General Porter is to take command of the Army of the Potomac. I hope it is so.

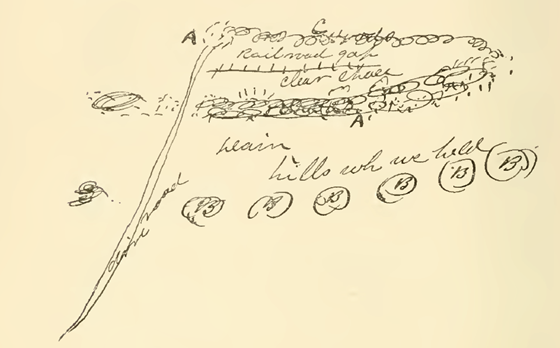

In regard to my being rash in going out so far that day, I wish to say a few words. I have always made it my intention to do everything the general has told me to do, and not come back and tell him that I could not find any one I was sent for or do anything I was sent to do. So this time I did not want to come back and tell him that I could not find the rear guard. The position of some of our troops and of the enemies’ batteries confused me, and made me go out too far. I will try and give you the position of our forces on the 2nd Bull Run field.

A was where the enemy had a battery placed during the day, that fired at us and finally withdrew, leaving only two pieces there. We advanced from the hills, B , and went across the plain into the woods A’. The enemy had a strong force in the woods C, and in the railroad gap in which they were posted. We tried to advance from the woods A’ across to C, and were repulsed by a terrible fire of grape, canister and musketry which mowed down the men like sheep. They had their batteries posted along the edge of woods C, and got a cross fire on us. The railroad gap served as a breastwork for them. Our left was turned by them and we were compelled to retreat to another range of hills behind the first, where towards night they were held in check by the Regulars, and time given us to retreat to Centreville, which was done in good order.

Some of the troops straggled dreadfully, but were all picked up by Franklin’s division. I will get a map of the country and show it to you as soon as I can. The general and staff were in the skirt of woods A; and when the enemy began shelling, it was a hot place. Their case-shot would burst and come whizzing around us, knocking the dust up under our horses and on all sides of us. Then would come the sharp zip of the bullet, and the fearful screech of the shot and shell. I saw at least a dozen round shot and pieces of shell, come flying towards us, and then only could one get an idea of the fearful force with which they were propelled. To see this dark object come by like a flash, strike the ground, and go ricochetting along with enormous bounds was fearful. Then our artillery on the hills B would open and the noise of the cannon, the whizzing of the shot and the sharp buzz of the bullets seemed to make the place a perfect hell. I saw more than a half a dozen men knocked down by these round shot but not injured, the ball knocking the ground from under them or covering [them] with dirt. After a while the wounded men who could walk came straggling out, and others were carried by their comrades. Soon well ones came running out by squads, and the general sent me to General Bayard of the cavalry to order him to form a line and stop them. We soon, however, had to abandon our position and fall back to the hills. Two batteries were lost during the fight, none of them from our corps. . . .

September 2 — This morning we renewed our march and moved within six miles of Fairfax Court House. We passed a great many wagons moving toward Fairfax and also some infantry marching in the same direction. We are now in Fairfax County, and camped on the Little River pike.

September 2, Tuesday. At Cabinet-meeting all but Seward were present. I think there was design in his absence. It was stated that Pope, without consultation or advice, was falling back, intending to retreat within the Washington intrenchments. No one seems to have had any knowledge of his movements, or plans, if he had any. Those who have favored Pope are disturbed and disappointed. Blair, who has known him intimately, says he is a braggart and a liar, with some courage, perhaps, but not much capacity. The general conviction is that he is a failure here, and there is a belief and admission on all hands that he has not been seconded and sustained as he should have been by McClellan, Franklin, Fitz John Porter, and perhaps some others. Personal jealousies and professional rivalries, the bane and curse of all armies, have entered deeply into ours.

Stanton said, in a suppressed voice, trembling with excitement, he was informed McClellan had been ordered to take command of the forces in Washington. General surprise was expressed. When the President came in and heard the subject-matter of our conversation, he said he had done what seemed to him best and would be responsible for what he had done to the country. Halleck had agreed to it. McClellan knows this whole ground; his specialty is to defend; he is a good engineer, all admit; there is no better organizer; he can be trusted to act on the defensive; but he is troubled with the “slows” and good for nothing for an onward movement. Much was said. There was a more disturbed and desponding feeling than I have ever witnessed in council; the President was greatly distressed. There was a general conversation as regarded the infirmities of McClellan, but it was claimed, by Blair and the President, he had beyond any officer the confidence of the army. Though deficient in the positive qualities which are necessary for an energetic commander, his organizing powers could be made temporarily available till the troops were rallied.

These, the President said, were General Halleck’s views, as well as his own, and some who were dissatisfied with his action, and had thought H. was the man for General-in-Chief, felt that there was nothing to do but to acquiesce, yet Chase earnestly and emphatically stated his conviction that it would prove a national calamity.

Pope himself had great influence in bringing Halleck here, and the two, with Stanton and Chase, got possession of McC.’s army and withdrew it from before Richmond. It has been an unfortunate movement. Pope is denounced as a braggart, unequal to the position assigned him.

Stanton and Halleck are apprehensive that Washington is in danger. Am sorry to see this fear, for I do not believe it among remote possibilities. Undoubtedly, after the orders of Pope to fall back, and the discontent and contentions of the generals, there will be serious trouble, but not such as to endanger the Capital. The military believe a great and decisive battle is to be fought in front of the city, but I do not anticipate it. It may be that, retreating within the intrenchments, our own generals and managers have inspired the Rebels to be more daring; perhaps they may venture to cross the upper Potomac and strike at Baltimore, our railroad communication, or both, but they will not venture to come here, where we are prepared and fortified with both army and navy to meet them.

In a conversation with Commodore Wilkes, who came up yesterday from Norfolk to take command of the Potomac Flotilla, consisting now of twenty-five vessels, he took occasion to express his high appreciation of McClellan as an officer. This can be accounted for in more ways than one. The two have been associated together in a severe disappointment, and persuade themselves they should have accomplished something important if they had not been interrupted. I have no doubt Wilkes, who has audacity, would have dashed on, and perhaps have compelled McClellan to do so, but with what prudence and discretion I am not assured. They both believe they would have taken Richmond. I apprehend they would have disagreed before getting there, even if McClellan could have been brought to the attempt. An adverse result has made them friends in belief, and they condemn the decision which led to their recall. I had no part in that decision. Probably should not have advised the order had I been consulted, although it may have been the proper military step. But whether recalled or not, McC. would never have struck a blow for Richmond, even under the impulsive urging of Wilkes, who is often inconsiderate; and so strife would have arisen between them.

Wilkes says they would have captured Richmond on the 1st inst., had there been no recall. His last letter to me, about the 27th, said they would have made an attempt by the 12th if let alone. I have no doubt that, could he have had the cooperation of the army, Wilkes would have struck a blow; perhaps he would alone.

Tuesday, 2d—There was some fighting south of town this morning and there is still some skirmishing. Old Patrick and several other citizens left, for they were afraid that the rebels would catch them and hang them. They had violated their oaths to support the Confederacy and then when the Union army took this section they had sworn to support the United States, and now thinking that this place would be retaken, they got out so as not to fall into the hands of the rebels.

Tuesday, September 2, 1862. Upton’s. — A clear, cold, windy day; bracing and Northern. No news except a rumor that the armies are both busy gathering up wounded and burying dead; that the enemy hold rather more of the battlefield than we do.

12:30 P. M. — I have seen several accounts of the late battles, with details more or less accurate. The impression I get is that we have rather the worst of it, by reason of superior generalship on the part of the Rebels.

9:30 P. M. — New and interesting scenes this P. M. The great army is retreating, coming back. It passes before us and in our rear. We are to cover the retreat if they are pursued. They do not look or act like beaten men; they are in good spirits and orderly. They are ready to hiss McDowell. When General Given announced that General McClellan was again leader, the cheering was hearty and spontaneous. The camps around us are numerous. The signal corps telegraphs by waving lights to the camps on all the heights. The scene is wild and glorious this fine night. Colonel White of the Twelfth and I have arranged our plans in case of an attack tonight. So to bed. Let the morrow provide for itself.

Tuesday, 2nd. Slept till rather late—up in time for Sandy’s breakfast. During the day wrote to Fannie Andrews. Delos called in the morning and I read Ella’s letter to him. Commented upon it. In the evening Charlie came up and I again reviewed Ella’s letter with him. Read some in Shakespeare and the latest papers. Received letter from home. Last one from Minnie E. Tenney.

Written from the Sea islands of South Carolina.

[Diary] September 2.

I think the last three days have been the darkest hours of the summer, for we have been so sure of evacuation. To-day it brightens a little. General Saxton was to have sailed, but Mr. French came with despatches that have prevented the General leaving at present. Captain Hooper is light-hearted again and ate some supper. The cavalry, which were all ordered North, had embarked when the counter-order came. They have disembarked and that does not look like evacuation.

News from the North that McClellan’s army is in confusion and Pope in retreat.

Chaplain Henry Hopkins to Georgeanna Woolsey.

Alexandria Hospital, Sept., 1862.

My dear Miss Woolsey: In great haste I write to say that to dispense anything which will do the bodies of these poor sufferers good will be a most welcome task. . . . Outside of the house, at the Mansion Hospital, we fed 1,500, 1,900, 2,500, and 1,600 patients passing North on successive days, so that those inside suffer some lack of care and of good food. Last night 75 came in from beyond the lines by flag of truce. I thought I had seen weary and worn-out human beings before, but these bloody, dirty, mangled men, who had lain on the battlefield, some of them two and three days, with wounds untouched since the first rude dressing, and had ridden from near Centreville in ambulances, were a new revelation. We cut their clothes from them, torn and stiff with their own blood and Virginia clay, and moved them inch by inch onto the rough straw beds; the poor haggard men seemed the personification of utmost misery. But some of them were happy. One nobleman who attracted me by the manliness of his very look in the midst of his sufferings, when I spoke to him of the strong consolations of a trust in the Saviour, threw his arms about my neck and told me, weeping, that for him they were more than sufficient. Some of these fellows I love like brothers and stand beside their graves for other reasons than that it is an official duty. . .

It was for such heroic sufferers as the “nobleman” described by Chaplain Hopkins that Mary wrote these verses:

.

“Mortally Wounded.”

.

I lay me down to sleep,

With little thought or care

Whether my waking find

Me here—or THERE!

.

A bowing, burdened head,

Only too glad to rest,

Unquestioning, upon

A Loving breast.

.

My good right hand forgets

Her cunning now;

To march the weary march

I know not how.

.

I am not eager, bold,

Nor strong,—all that is past!

I am willing not to do,

At last, at last !

.

My half-day’s work is done,

And this is all my part:

I give a patient God

My patient heart;

.

And grasp His banner still,

Though all its blue be dim;

These stripes, no less than stars,

Lead after Him.

.

Weak, weary and uncrowned,

I yet to bear am strong;

Content not even to cry,

“How long ! How long!”

September 2.—Passed through Richmond at 7 A. M. Very nice little city. Saw quite a number of prisoners. Crossed Kentucky River at 12 o’clock; camped in a beautiful country, nine miles from Lexington.