Bivouac south of Sharpsburg, Va.,

Tuesday, September 23, 1862.

Dear Sister L.:—

I think I wrote to you last from Hall’s Hill. Our stay there was short. We spent several days in marching about between Hall’s Hill, Washington and Alexandria, and then crossed over into Maryland. There, that reminds me that I have dated my letter in Virginia, a habit I have fallen into from being so long in that accursed state, but this time my habit led me astray and I am still in Maryland, and so is Sharpsburg, or what is left of it. It is a village about the size of Panama, and in passing through I could scarcely see a house that was not riddled by musketry or pierced by cannon balls. That town has had a taste of war it will not soon forget.

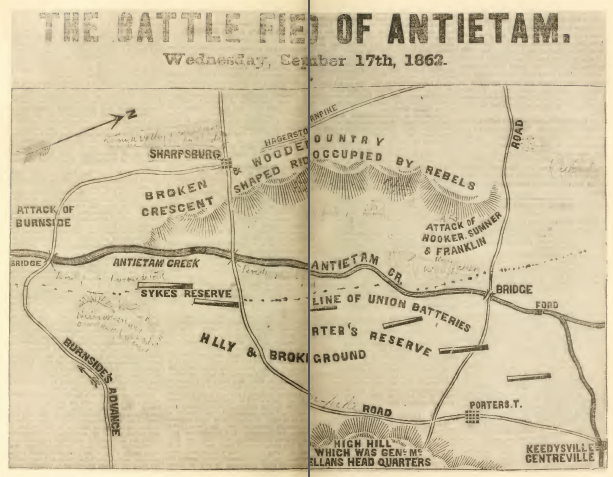

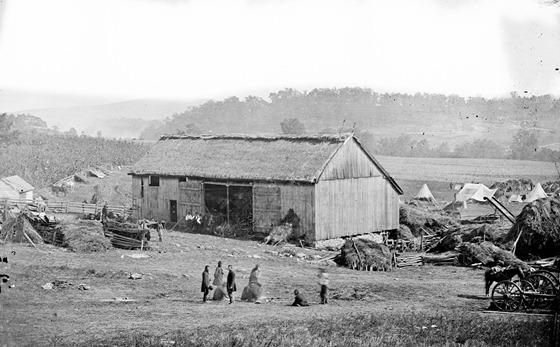

We have had quite a march in Maryland from Washington up through Frederick City, across the two ranges of the Blue Ridge mountains and the Cumberland valley between, and then down on the west side of the mountains to the Potomac above Harper’s Ferry, where we are now. I shall always remember the march through Maryland as among the most pleasant of my experiences as a soldier. The roads were splendid and the country as beautiful a country as I ever saw. It has but little of the desolate appearance of the devastated Old Dominion, but everywhere landscapes of exquisite beauty meet the eye. Pretty villages are frequent, and pretty girls more so, and instead of gazing at passing soldiers with scorn and contempt, they were always ready with a pleasant word and a glass of water. I almost forgot the war and the fact that I was a soldier as I gained the summit of the first range of mountains, and the Cumberland valley was spread out before me. I was in love with the “Sunny South.” The brightest, warmest, richest landscape I ever saw lay sleeping in the mellow sunlight of a September afternoon. Oh, how I did enjoy the pure sparkling cold water gushing from the rocks after drinking so long from the swamps of the Chickahominy and puddles by the roadside in Virginia! I did think when I saw the luxury in which the aristocratic Ruffin lived, the beauty and elegance of his country villa, that a man might be happy there, but when I reflect that it is a palace in the desert and that but few can live as he did, I say, give me the humbler dwellings but better farms of Maryland, where one man does not own all that joins him, but his neighbors can live comfortably, too. It don’t take ten thousand acres here to support one family. Maryland will yet be free and then she will be a noble state. One thing I noticed so different from what we see in the north. There, in the vicinity of cities and large towns, the land is always more carefully tilled and more productive than it is farther from the markets. Here, just the opposite is the case. As we receded from Washington and approached the mountains, the country increased in richness and in beauty. Maybe you think I am getting too warm in my praises of a southern state. Perhaps I am, but it seemed such a relief to get into a civilized country after a year’s sojourn in the deserts of Virginia, among the few Arabs left of the original population, that I grew enthusiastic at once. But I have seen war in Maryland, too. I was a spectator, though not a participant, in the greatest battle ever fought on this continent—the battle of Antietam. I stood on a hill where a battery of twenty pounders was dealing death to the enemies of our country, and there, stretched out before me, was a rough, rolling valley sloping away to the Potomac. The mountains do not rise abruptly out of a level country, but for several miles on either side the ground gradually rises. The country is broken and hilly, affording strong positions for defense, and on the western slope of the mountains along the Antietam river, the battle was fought. Our division was held in reserve near the center of the line, and from where I stood I could trace our lines extending in a semi-circle for several miles. The valley was wrapped in smoke, but the white wreaths curling from the cannon’s mouth, the boom of the report and the scream of the shell showed the position of the batteries, and the sharp rattle of musketry deepening to a roar told where the most desperate fighting was going on.

I felt proud, exultant, that night when I knew the enemy had been driven from two to three miles at every point. Many, many were the homes made desolate that day, but it is not to us as though we had lost as many and yet gained nothing. The victory is ours, and the enemy took advantage of an armistice granted them to bury the dead and care for the wounded, to ingloriously retreat across the river.

Colonel (late Captain) H. L. Brown’s new Erie regiment arrived here lately and one of our boys who was over to see them told me that he saw a young man there who inquired for me and said he was my brother. Can it be possible that E. has enlisted? The last I heard from him was at Hall’s Hill. He wrote that he would take my advice and stay at home; he had given up the idea. I cannot understand why, if he has enlisted, he did not come and enlist with me.

I am waiting news from home with anxiety. I have had but few letters lately. Our mail comes very seldom. In fact, we are constantly on the move. I have not pitched a tent but once since I left Virginia, sleeping every night on the ground, rolled up in a blanket.

I hope you will write often whether you hear from me or not. I will write as often as I can.