Rienzi, Sunday, Sept. 7. Arose to the sound of the bugle at 3 A. M. Prepared for a general inspection, but Captain, apprehending a move, did not call us out. Drew good bunks from the old camp of 2nd Missouri. After roll call at 9 P. M. I went to bed hoping to have a good night’s rest, but I was doomed to disappointment, for ere two hours had elapsed, we were awakened by Corporal Dixon telling us to pack up all our clothing and be in readiness to march. We of course obeyed and waited for further orders, when about midnight, “Strike your tents” was given. This done, the mules began driving in, loading was commenced, the horses harnessed, and by one o’clock all was ready to march. That which could not be taken was piled up ready for the march, but the order did not come, so we were obliged to pick our place and lay down for a short and uneasy sleep.

Friday, September 7, 2012

September 7 — It was midnight when we left the Southern Confederacy last night, forded the Potomac, and landed in the United States, in Montgomery County, Maryland.

We marched till the after-part of the night, and today till two o’clock, when we arrived at Frederick City. We halted there an hour or so, fed our horses, then moved to Urbana, seven miles southeast of Frederick.

Where we forded the Potomac last night it is about two and a half feet deep and four hundred yards wide, a gentle current and smooth bottom. In our march to-day we only touched the suburb of Frederick and did not go into the city, but saw its spires and cupolas. This town is situated in a beautiful country and surrounded by rich and fertile land, well cultivated. Two miles south of the city the main stem of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad crosses the Monocacy, which is but a small stream, yet the railroad bridge that spans it is not a small one, and is substantially constructed of stone and iron. Jackson’s men were destroying it today when we passed. We arrived at Urbana at sunset, and camped.

September 7. The report prevalent yesterday that the Rebels had crossed the upper Potomac at or near the Point of Rocks is confirmed, and it is pretty authentic that large reinforcements have been added.

Found Chase in Secretary’s room at the War Department with D. D. Field. No others present. Some talk about naval matters. Field censorious and uncomfortable. General Pope soon came in but stayed only a moment. Was angry and vehement. He and Chase had a brief conversation apart, when he returned to Stanton’s room.

When I started to come away, Chase followed, and after we came down stairs asked me to walk with him to the President’s. As we crossed the lawn, he said with emotion everything was going wrong. He feared the country was ruined. McClellan was having everything his own way, as he (Chase) anticipated he would if decisive measures were not promptly taken for his dismissal. It was a reward for perfidy. My refusal to sign the paper he had prepared was fraught with great evil to the country. I replied that I viewed that matter differently. My estimate of McClellan was in some respects different from his. I agreed he wanted decision, that he hesitated to strike, had also behaved badly in the late trouble, but I did not believe he was unfaithful and destitute of patriotism. But aside from McClellan, and the fact that it would, with the feeling which pervaded the army, have been an impolitic step to dismiss him, the proposed combination in the Cabinet would have been inexcusably wrong to the President. We had seen the view which the President took of the matter and how he felt at the meeting of the Cabinet on Tuesday.

From what I have seen and heard within the last few days, the more highly do I appreciate the President’s judgment and sagacity in the stand he made, and the course he took. Stanton has carried his dislike or hatred of McC. to great lengths, and from free intercourse with Chase has enlisted him, and to some extent influenced all of us against that officer, who has failings enough of his own to bear without the addition of Stanton’s enmity to his own infirmities. Seward, in whom McC. has confided more than any member of the Administration, from the common belief that Seward was supreme, yielded to Stanton’s malignant feelings, and yet, not willing to encounter that officer, he went off to Auburn, expecting the General would be disposed of whilst he was away. The President, who, like the rest of us, has seen and felt McClellan’s deficiencies and has heard Stanton’s and Halleck’s complaints more than we have, finally, and I think not unwillingly, consented to bring Pope here in front of Washington; was also further persuaded by Stanton and Chase to recall the army from Richmond and turn the troops over to Pope. Most of this originated, and has been matured, in the War Department, Stanton and Chase being the pioneers, Halleck assenting, the President and Seward under stress of McClellan’s disease “the slows,” and with the reverses before Richmond, falling in with the idea that a change of commanders and a change of base was necessary. The recall of the army from the vicinity of Richmond I thought wrong, and I know it was in opposition to the opinion of some of the best military men in the service. Placing Pope over them roused the indignation of many. But in this Stanton had a purpose to accomplish, and in bringing first Pope here, then by Pope’s assistance and General Scott’s advice bringing Halleck, and concerting measures which followed, he succeeded in breaking down and displacing McClellan, but not in dismissing and disgracing him. This the President would not do or permit to be done, though he was more offended with McC. than he ever was before. In a brief conversation with him as we were walking together on Friday, the President said with much emphasis: “I must have McClellan to reorganize the army and bring it out of chaos, but there has been a design, a purpose in breaking down Pope, without regard of consequences to the country. It is shocking to see and know this; but there is no remedy at present, McClellan has the army with him.”

My convictions are with the President that McClellan and his generals are this day stronger than the Administration with a considerable portion of this Army of the Potomac. It is not so elsewhere with the soldiers, or in the country, where McClellan has lost favor. The people are disappointed in him, but his leading generals have contrived to strengthen him in the hearts of the soldiers in front of Washington.

Chase and myself found the President alone this Sunday morning. We canvassed fully the condition of the army and country. Chase took an early opportunity, since the report of Pope was suppressed, to urge upon the President the propriety of some announcement of the facts connected with the recent battles. It was, he said, due to the country and also to Pope and McDowell. I at once comprehended why Chase had invited me to accompany him in this visit. It was that it might appear that we were united on this mission. I therefore promptly stated that this was the first time I had heard the subject broached. At a proper time, it seemed to me, there would be propriety in presenting a fair, unprejudiced, and truthful statement of late disasters. The country craved to know the facts, but the question was, Could we just now with prudence give them? Disclosing might lead to discord and impair the efficiency of the officers. The President spoke favorably of Pope, and thought he would have something prepared for publication by Halleck.

When taking a walk this Sunday evening with my son Edgar, we met on Pennsylvania Avenue, near the junction of H Street, what I thought at first sight a squad of cavalry or mounted men, some twenty or thirty in number. I remarked as they approached that they seemed better mounted than usual, but E. said the cavalcade was General McClellan and his staff. I raised my hand to salute him as they were dashing past, but the General, recognizing us, halted the troop and rode up to me by the sidewalk, to shake hands, he said, and bid me farewell. I asked which way. He said he was proceeding to take command of the onward movement. “Then,” I added, “you go up the river.” He said yes, he had just started to take charge of the army and of the operations above. “Well,” said I, “onward, General, is now the word; the country will expect you to go forward.” “That,” he answered, “is my intention.” “Success to you, then, General, with all my heart.” With a mutual farewell we parted.

This was our first meeting since we parted at Cumberland on the Pamunkey in June, for we each had been so occupied during the three or four days he had been in Washington that we had made no calls. On several occasions we missed each other. In fact, I had no particular desire to fall in with any of the officers who had contributed to the disasters that had befallen us, or who had in any respect failed to do their whole duty in this great crisis. While McClellan may have had some cause to be offended with Pope, he has no right to permit his personal resentments to inflict injury upon the country. I may do him injustice, but I think his management has been generally unfortunate, to say the least, and culpably wrong since his return from the Peninsula.

He has now been placed in a position where he may retrieve himself, and return to Washington a victor in triumph, or he may, as he has from the beginning, wilt away in tame delays and criminal inaction. I would not have given him the command, nor have advised it, strong as he is with the army, had I been consulted; and I feel sad that he has been so intrusted. It may, however, be for the best. There are difficulties in the matter that can scarcely be appreciated by those who do not know all the circumstances. The army is, I fear, much demoralized, and its demoralization is much of it to be attributed to the officers whose highest duty it is to prevent it. To have placed any other general than McClellan, or one of his circle, in command would be to risk disaster. It is painful to entertain the idea that the country is in the hands of such men. I hope I mistake them.

Sunday, 7th—There have been no rebels to see us yet. Things are very quiet today; the weather being so hot, no one cares to stir.

Sunday, September 7. Washington City. — Left the suburbs of Washington to go on Leesboro Road about twelve to fifteen miles. Road full of horse, foot, and artillery, baggage and ambulance waggons. Dust, heat, and thirst. “The Grand Army of the Potomac” appeared to bad advantage by the side of our troops. Men were lost from their regiments; officers left their commands to rest in the shade, to feed on fruit; thousands were straggling; confusion and disorder everywhere. New England troops looked well; Middle States troops badly; discipline gone or greatly relaxed.

On coming into camp Major-General Reno, in whose corps we are, rode into the grounds occupied by General Cox’s troops in a towering passion because some of the men were taking straw or wheat from a stack. Some were taking it to feed to horses in McMullen’s Battery and to cavalry horses; some in the Twenty-third Regiment were taking it to lie upon. The ground was a stubble field, in ridges of hard ground. I saw it and made no objection. General Reno began on McMullen’s men. He addressed them: “You damned black sons of bitches.” This he repeated to my men and asked for the colonel. Hearing it, I presented myself and assumed the responsibility, defending the men. I talked respectfully but firmly; told him we had always taken rails, for example, if needed to cook with; that if required we would pay for them. He denied the right and necessity; said we were in a loyal State, etc., etc. Gradually he softened down. He asked me my name. I asked his, all respectfully done on my part. He made various observations to which I replied. He expressed opinions on pilfering. I remarked, in reply to some opinion, substantially: “Well, I trust our generals will exhibit the same energy in dealing with our foes that they do in the treatment of their friends.” He asked me, as if offended, what I meant by that. I replied. “Nothing — at least, I mean nothing disrespectful to you.” (The fact was, I had a very favorable opinion of the gallantry and skill of General Reno and was most anxious to so act as to gain his good will.) This was towards the close of the controversy, and as General Reno rode away the men cheered me. I learn that this, coupled with the remark, gave General Reno great offense. He spoke to Colonel Ewing of putting colonels in irons if their men pilfered! Colonel Ewing says the remark “cut him to the quick,” that he was “bitter” against me. General Cox and Colonel Scammon (the latter was present) both think I behaved properly in the controversy.

7h.—Having marched all night, I slept until awakened by the city bells, the first I had heard for nearly eight months. How forcibly I felt the application to the wilderness in which we had been, of Selkirk’s soliloquy:

..

“The sound of the church-going bells

These valleys and rocks never heard,—

Never sighed at the sound of a knell,

Nor smiled when a Sabbath appeared.”

..

It has been a beautiful Sunday, and we have been all day “lying around loose,” (no tents pitched) :awaiting orders.

Had it not been for this move, I should now have been packing up for home. We supposed that we were to remain idle in garrison this winter, and my Colonel promised that he would approve and aid me in getting the acceptance of my resignation. On appearing at his tent four days ago, with my resignation, I received orders for this march. I did not present it, and do not know now when I shall; but not on the eve of battle.

Yesterday, (I learn,) General McClellan was made Commander-in-Chief of the combined armies of Virginia and the Potomac. This looks very much as if there was some truth in the statements of his friends, that he had been held back and controlled in his movements by the President and General Halleck; very much, in fact, as if it were an acknowledgment that General McClellan had had but little voice in the management of the war, and that his superior officers were in the wrong. Should this prove true, I shall have much to atone for in the wrong I have done him in this journal. How gladly will I make all the amends in my power, should he only now prove to be the man for the occasion, and close up this war, as he has promised to do. This prompt and sudden move, too; this all night march in pursuit of the enemy, on the very first day of his accession to the command, gives additional ground for a belief in the hypothesis. God grant that it may be true, and that our General may by saving the country, retrieve his own waning popularity.

Sunday, 7th. At breakfast Capt. Seward and Bernard said Nettleton had returned. After breakfast saw him and received a note from Sister Melissa expressing her delight at the visit with “her dear Lu” and giving a description of Minnie’s marriage. Sent a nice handkerchief. Read some during the day. In the evening Capt. Nettleton called, invited me to walk and gave me a minute description of his call at Chicago for Melissa; his visit on the road; visit and business with Tod, about colonel etc.; visit at home, and Minnie’s marriage. Enjoyed all. Capt. Welsh interrupted us and I went to my quarters.

Sunday, 7th.—Passed through Holmansville at 12 M. Camped for the night two miles north of Williamstown, after making a march of thirty miles in twenty-six hours.

SEPTEMBER 7TH.—We see by the Northern papers that Pope claimed a great victory over Lee and Jackson! It was too much even for the lying editors themselves! The Federal army being hurled back on the Potomac, and then compelled to cross it, it was too transparently ridiculous for the press to contend for the victory. And now they confess to a series of defeats from the 26th June to the culminating calamity of the 30th August. They acknowledge they have been beaten—badly beaten—but they will not admit that our army has crossed into Maryland. Well, Lee’s dispatch to the President is dated “Headquarters, Frederick City.” We believe him.

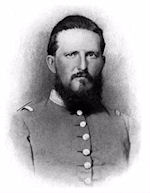

“The assault upon our line was very severe, and for a while the tide of battle seemed to turn against us; but our men stubbornly resisted the assault, and soon the enemy’s line gave way”–Letters from Elisha Franklin Paxton.

Frederick, Md., Sunday, September 7,1862.

Your two last letters came to hand yesterday, and I was indeed very happy to hear from you. The date of my letter will surprise you. You would have thought it hardly possible that the fortunes of war should have so turned in our favor that this quiet Sabbath would find us here quietly encamped beyond the limits of our own Confederacy. It has cost us much of our best blood and much hardship, but it is a magnificent result, which, I trust, will secure our recognition in Europe, and be a step at least towards peace with our enemies. We left the Rappahannock two weeks ago to-morrow, and such a week as the first was has no parallel in the war. Two days’ severe march brought us about fifty miles to Manassas. That night we had an engagement with the enemy, in which the place was captured and some prisoners. The next day there was another battle, in which Mr. Newman was wounded. That night—Wednesday—we evacuated the place and took up our position adjoining the old battle-ground, and that evening we had another severe engagement, in which Maj .-Gen. Ewell was severely wounded and our loss very heavy. The next day—Friday —we were attacked by the enemy in much larger force, but we repulsed the enemy and at night both armies occupied about the same ground. We expected the battle to be renewed the next morning. The enemy had time to collect his whole force, Pope and McClellan combined, and we had brought up all we had on this side of the Rappahannock. For a while, the lines were unusually quiet, but after a while the picket-firing began to increase, and soon the whole line was engaged. The assault upon our line was very severe, and for a while the tide of battle seemed to turn against us; but our men stubbornly resisted the assault, and soon the enemy’s line gave way, flying in confusion, our artillery playing upon them as they retreated. Our lines were then pushed forward, and by night the enemy was driven from every position. It was a splendid victory, partly fought on the same ground with the battle of Manassas last year. We sustained a very heavy loss, but how much I have no idea. The next day we moved towards Fairfax C. H. The next day—Monday—we had another severe engagement. Tuesday we spent at rest and in cooking. Wednesday we started in this direction, and reached here early on yesterday, without meeting any further obstruction. What next—where do we go—and what is to be done? We will probably know by the end of next week what our General means to do with us. I think it likely we will not stay here, and that this time next week will find us either in Pennsylvania or Baltimore.

I heartily wish with you that the war was over and we were all at home again. But our success depends upon the pertinacity with which we stick to the fight. I think it may not last through another winter. I spend but little time now thinking about business on the farm. I trust it all to you. My duties here are onerous and responsible, occupying my time and mind so completely that I have but little opportunity to think of much else. Not enough, however, to keep me from thinking of dear wife and little ones left at home, and fondly hoping that the day may soon come when I will be with them. It may never come. My fate may be that of many others. Whatever the future may have in store for me, I trust that I am prepared to meet it with becoming resignation.

And now, darling, I will take leave of you. Think of me often, and believe me, with much love, ever yours.