September 22.—I read aloud to Grandfather this evening the Emancipation Proclamation issued as a war measure by President Lincoln, to take effect January 1, liberating over three million slaves. He recommends to all thus set free, to labor faithfully for reasonable wages and to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defense, and he invokes upon this act “the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”

Saturday, September 22, 2012

Monday, 22nd.—A beautiful morning and all quiet, except that the officers are pitching tents and fixing up tables, as if for a stay. But that is no indication of what is in store for us; even before night we may be ordered to pull up and move again. But this would be very cruel. Our poor, worn out enemy, having fought and been driven for seven days, and now being entirely without provisions, must be exhausted and need rest. How cruel it would be to pursue him, under these circumstances. The kind heart of our Commander can entertain no such idea.

In the afternoon, I rode up to Williamsport and found the town full of soldiers. A little incident occurred, which I shall notice. Walking through the streets I encountered a young lady, fresh, rosy, plump and pretty. Her look told me that she would like to speak to me, but she was hesitating as to the propriety of doing so. I spoke, and she at one commenced a conversation on the war. She said that last night there were three thousand rebels encamped near by, and that we might easily have captured them. She pointed out to me with much military tact, how they might have been surrounded, and then said she could not get any one to come in the night and inform us, though only two miles away; that she got ready to come herself, but (with tears and sobs) that her father would not let her, and only because it was night. Poor child, I did want to kiss her.

Not for the sake of the kiss. Oh, no!

But only for sympathy, you know—you know.

I have suffered some to-day, from a most singular pain in my finger. It is peculiar, and runs up the lymphatics to the arm and shoulder. Ordered to move at 7 tomorrow morning.

Headquarters 5th Army Corps,

Camp near Shepardstown, Sept. 22.

Dear Father, — . . . The enemy are still on the opposite side of the river and I do not know what measures will be taken to drive them off. Meanwhile we are getting a day’s rest, which every one needs badly enough. I am in the saddle almost all the time, and have very few chances to write. I feel so tired after coming in at night, that I go to bed instantly.

We have four guns here at headquarters which were taken the other evening from the other side of the Potomac. One of them is a gun taken from Griffin’s Battery at Bull Run No. 1. Griffin, who is now a general in the corps, is well pleased at getting the gun back, and is going to have it placed with his old battery.

I went over the river this afternoon with a message to Colonel Webb, who was over there with a flag of truce. We sent over some paroled prisoners and also applied for leave to bury our dead, who were killed in the skirmish on that side. I saw Colonel Lee,[1] who was in College with me, being in the class of ’58. He now commands the 9th Virginia Cavalry. He said that their men behaved disgracefully in the fight of September 17 and ran like sheep. He gave as the reason, that they were starved and had nothing to eat. When the 4th Michigan crossed the river the other evening, he said, they drove a whole brigade of rebels, who ran shamefully. These are Colonel Lee’s own words. He also said that the rebels deserted 27 guns that evening, of which we got four, not knowing where the rest were. There is no doubt that the rebels are mighty hard up for food and clothing. There were some forty of our dead there, and all of them had their shoes taken and pockets rifled. The faces of the dead were horrible. Some could hardly be distinguished from negroes, their faces were so black. I had charge of burying a good many of them. There are some 1200 rebels wounded, in the barns and hospitals around here, most of whom will be paroled. . . .

I have every reason to think General Porter is satisfied with me, from the messages he intrusts to me, many of which are very important.

September 22 — Still on picket. From our post we can see the white tents of an extensive camp of Yankees, way up on South Mountain in Maryland, just beyond Maryland Heights.

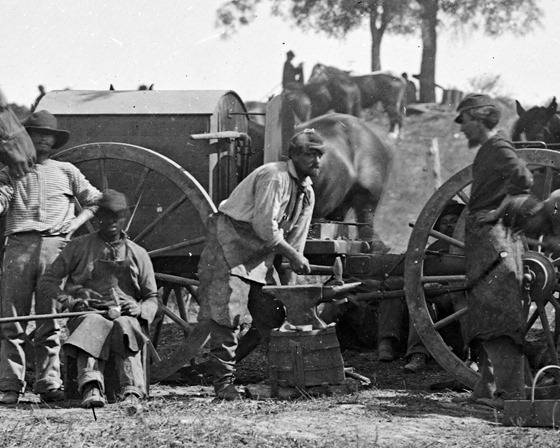

Antietam, Md. Blacksmith shoeing horses at headquarters, Army of the Potomac.

Photographed by Alexander Gardner.

Library of Congress image.

Monday Night, September 22d.—Probably the most desperate battle of the war was fought last Wednesday near Sharpsburg, Maryland. Great loss on both sides. The Yankees claim a great victory, while our men do the same. We were left in possession of the field on Wednesday night, and buried our dead on Thursday. Want of food and other stores compelled our generals to remove our forces to the Virginia side of the river, which they did on Thursday night, without molestation. This is all I can gather from the confused and contradictory accounts of the newspapers.

September 22. A special Cabinet-meeting. The subject was the Proclamation for emancipating the slaves after a certain date, in States that shall then be in rebellion. For several weeks the subject has been suspended, but the President says never lost sight of. When it was submitted, and now in taking up the Proclamation, the President stated that the question was finally decided, the act and the consequences were his, but that he felt it due to us to make us acquainted with the fact and to invite criticism on the paper which he had prepared. There were, he had found, not unexpectedly, some differences in the Cabinet, but he had, after ascertaining in his own way the views of each and all, individually and collectively, formed his own conclusions and made his own decisions. In the course of the discussion on this paper, which was long, earnest, and, on the general principle involved, harmonious, he remarked that he had made a vow, a covenant, that if God gave us the victory in the approaching battle, he would consider it an indication of Divine will, and that it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation. It might be thought strange, he said, that he had in this way submitted the disposal of matters when the way was not clear to his mind what he should do. God had decided this question in favor of the slaves. He was satisfied it was right, was confirmed and strengthened in his action by the vow and the results. His mind was fixed, his decision made, but he wished his paper announcing his course as correct in terms as it could be made without any change in his determination. He read the document. One or two unimportant amendments suggested by Seward were approved. It was then handed to the Secretary of State to publish to-morrow. After this, Blair remarked that he considered it proper to say he did not concur in the expediency of the measure at this time, though he approved of the principle, and should therefore wish to file his objections. He stated at some length his views, which were substantially that we ought not to put in greater jeopardy the patriotic element in the Border States, that the results of this Proclamation would be to carry over those States en masse to the Secessionists as soon as it was read, and that there was also a class of partisans in the Free States endeavoring to revive old parties, who would have a club put into their hands of which they would avail themselves to beat the Administration.

September 22. A special Cabinet-meeting. The subject was the Proclamation for emancipating the slaves after a certain date, in States that shall then be in rebellion. For several weeks the subject has been suspended, but the President says never lost sight of. When it was submitted, and now in taking up the Proclamation, the President stated that the question was finally decided, the act and the consequences were his, but that he felt it due to us to make us acquainted with the fact and to invite criticism on the paper which he had prepared. There were, he had found, not unexpectedly, some differences in the Cabinet, but he had, after ascertaining in his own way the views of each and all, individually and collectively, formed his own conclusions and made his own decisions. In the course of the discussion on this paper, which was long, earnest, and, on the general principle involved, harmonious, he remarked that he had made a vow, a covenant, that if God gave us the victory in the approaching battle, he would consider it an indication of Divine will, and that it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation. It might be thought strange, he said, that he had in this way submitted the disposal of matters when the way was not clear to his mind what he should do. God had decided this question in favor of the slaves. He was satisfied it was right, was confirmed and strengthened in his action by the vow and the results. His mind was fixed, his decision made, but he wished his paper announcing his course as correct in terms as it could be made without any change in his determination. He read the document. One or two unimportant amendments suggested by Seward were approved. It was then handed to the Secretary of State to publish to-morrow. After this, Blair remarked that he considered it proper to say he did not concur in the expediency of the measure at this time, though he approved of the principle, and should therefore wish to file his objections. He stated at some length his views, which were substantially that we ought not to put in greater jeopardy the patriotic element in the Border States, that the results of this Proclamation would be to carry over those States en masse to the Secessionists as soon as it was read, and that there was also a class of partisans in the Free States endeavoring to revive old parties, who would have a club put into their hands of which they would avail themselves to beat the Administration.

The President said he had considered the danger to be apprehended from the first objection, which was undoubtedly serious, but the objection was certainly as great not to act; as regarded the last, it had not much weight with him.

The question of power, authority, in the Government to set free the slaves was not much discussed at this meeting, but had been canvassed by the President in private conversation with the members individually. Some thought legislation advisable before the step was taken, but Congress was clothed with no authority on this subject, nor is the Executive, except under the war power, — military necessity, martial law, when there can be no legislation. This was the view which I took when the President first presented the subject to Seward and myself last summer as we were returning from the funeral of Stanton’s child, — a ride of two or three miles from beyond Georgetown. Seward was at that time not at all communicative, and, I think, not willing to advise, though he did not dissent from, the movement. It is momentous both in its immediate and remote results, and an exercise of extraordinary power which cannot be justified on mere humanitarian principles, and would never have been attempted but to preserve the national existence. The slaves must be with us or against us in the War. Let us have them. These were my convictions and this the drift of the discussion.

The effect which the Proclamation will have on the public mind is a matter of some uncertainty. In some respects it would, I think, have been better to have issued it when formerly first considered.

There is an impression that Seward has opposed, and is opposed to, the measure. I have not been without that impression myself, chiefly from his hesitation to commit nimself, and perhaps because action was suspended on his suggestion. But in the final discussion he has as cordially supported the measure as Chase.

For myself the subject has, from its magnitude and its consequences, oppressed me, aside from the ethical features — of the question. It is a step in the progress of this war which will extend into the distant future. A favorable termination of this terrible conflict seems more remote with every movement, and unless the Rebels hasten to avail themselves of the alternative presented, of which I see little probability, the war can scarcely be other than one of emancipation to the slave, or subjugation, or submission to their Rebel owners. There is in the Free States a very general impression that this measure will insure a speedy peace. I cannot say that I so view it. No one in those States dare advocate peace as a means of prolonging slavery, even if it is his honest opinion, and the pecuniary, industrial, and social sacrifice impending will intensify the struggle before us. While, however, these dark clouds are above and around us, I cannot see how the subject can be avoided. Perhaps it is not desirable it should be. It is, however, an arbitrary and despotic measure in the cause of freedom.

Monday, 22d—No news of importance. Rain last night. Foraging parties are bringing in all the fresh pork that we can use, besides plenty of sweet potatoes. Our crackers, having been kept in storage so long, are musty and full of the weevil web, and there are no trains from Corinth to bring a fresh supply. We often clean them the best we can and bake them again in ashes or in skillets.

Middletown, Monday, September 22, 1862.

Dear Uncle : — I am still doing well. I am looking for Lucy. My only anxiety is lest she has trouble in finding me. Indeed, I am surprised that she is not here already. I shall stay here about ten days or two weeks longer, then go to Frederick and a few days afterwards to Washington. About the 15th or 20th October, I can go to Ohio, and if my arm cures as slowly as I suspect it will, I may come via Pittsburgh and Cleveland to Fremont and visit you. I do not see how I can be fit for service under two months.

The Eighth Regiment was in the second battle and suffered badly. You must speak well of “old Frederick” hereafter. These people are nursing some thousands of our men as if they were their own brothers. McClellan has done well here. The Harpers Ferry imbecility or treachery alone prevented a crushing of the Rebels. Love to all. Send me papers, etc., here “care Jacob Rudy.”

Do you remember your Worthington experience in 1842? Well this is it. I don’t suffer as much as you did, but like it.

Middletown is eight miles west of Frederick on the National Road. The nearest telegraph office is at Frederick. Two thirds of the wounded men of my regiment have gone to Frederick. The worst cases are still here. In my regiment, four captains out of eight present were wounded, thirty-nine men killed, one hundred and thirty-seven wounded, and seven missing. I expect about twenty to twenty-five of the wounded to die. The New York Times account gives us the nearest justice of anybody in its details of the Sunday fight but we are all right. Everybody knows that we were the first in and the last out, and that we were victorious all the time. How happy the men are — even the badly wounded ones. One fellow shot through the body has gathered up a banjo and makes the hospital ring with negro songs!

Good-bye,

H.

S. BIRCHARD.

Monday, 22nd. Breakfast at 4:15 A. M. Marched at sunrise, passing through Greenfield, a very pretty little village. One encouraging sign, seldom seen of late months, a comfortable schoolhouse. Stopped two miles out of town, by a spring for dinner. Capt., one or two others and myself explored a cave near by. Found the layers of stone filled with shells and all sorts of stones. Several lizards lying about. Learned afterwards that some bushwhackers were watching us from the bluffs above. Here the country changed from boundless prairie to woodlands and hills. Like the variety better. Encamped for the night after riding 7 miles farther. Slept beneath a clump of trees with Archie.