September 25 —This morning we were ordered up the Berryville pike. We went about three miles toward Berryville, then came right back to camp. After we got back we moved camp to Leetown, which is seven miles from Charlestown, on the Smithfield and Shepherdstown road.

September 2012

September 25, Thursday. Had some talk to-day with Chase on financial matters. Our drafts on Barings now cost us 29 percent. I object to this as presenting an untrue statement of naval expenditures, — unjust to the Navy Department as well as incorrect in fact. If I draw for $100,000 it ought not to take from the naval appropriation $129,000. No estimates, no appropriations by Congress, embrace the $29,000 brought on by the mistaken Treasury policy of depreciating the currency. I therefore desire the Secretary of the Treasury to place $100,000 in the hands of the Barings to the credit of the Navy Department, less the exchange. This he declines to do, but insists on deducting the difference between money and inconvertible paper, which I claim to be wrong, because in our foreign expenditures the paper which his financial policy forces upon us at home is worthless abroad. The depreciation is the result of a mistaken financial policy, and illustrates its error and tendency to error.

The departure from a specie standard and the adoption of an irredeemable paper currency deranges the finances and is fraught with disastrous consequences. This vitiation of the currency is the beginning of evil, — a fatal mistake, which will be likely to overwhelm Chase and the Administration, if he and they remain here long enough.

Had some conversation with Chase relating to the War. He is much discouraged, thinks the President is, believes the President is disposed to let matters take their course, deplores this state of things but can see no relief. I asked if the principal source of the difficulty was not in the fact that we actually had not a War Department. Stanton is dissatisfied, and he and those under his influence do not sustain and encourage McClellan, yet he needs to be constantly stimulated, inspired, and pushed forward. It was, I said, apparent to me, and I thought to him, that the Secretary of War, though arrogant and often offensive in language, did not direct army movements; he appears to have something else than army operations in view. The army officers here, or others than he, appear to control military movements. Chase was disturbed by my remarks. Said Stanton had not been sustained, and his Department had become demoralized, but he (C.) should never consent to remain if Stanton left. I told him he misapprehended me. I was not the man to propose the exclusion of Stanton, or any one of our Cabinet associates, but we must look at things as they are and not fear to discuss them. It was our duty to meet difficulties and try to correct them. It was wrong for him, or any one, to say he would not remain and do his duty if the welfare of the country required a change of policy or a personal change in any one Department. If Stanton was militarily unfit, indifferent, dissatisfied, or engaged in petty personal intrigues against a man whom he disliked, to the neglect of the duties with which he was intrusted, or had not the necessary administrative ability, was from rudeness or any other cause offensive, we ought not to shut our eyes to the fact. If a man were to be brought into the War Department, or proposed to be brought in, with heart and mind in the cause, sincere, earnest, and capable, who would master the generals and control them, break up cliquism, and bring forward those officers who had the highest military qualities, we ought not to object to it. I knew not that such a change was thought of. Without controverting or assenting, he said Stanton had given way just as Cameron did, and in that way lost command and influence. It is evident that Chase takes pretty much the same views that I do, but has not made up his mind to act upon his convictions. He feels that he has been influenced by Stanton, whose political and official support he wants in his aspirations, but begins to have a suspicion that S. is unreliable. They have consulted and acted in concert and C. had flattered himself that he had secured S. in his interest, but must have become aware that there is a stronger tie between Seward and Stanton than any cord of his. C. is not always an acute and accurate reader of men, but he cannot have failed to detect some of the infirm traits of Stanton. When I declined to make myself a party to the combination against McClellan and refused to sign the paper which Chase brought me, Stanton, with whom I was not very intimate, spoke to me in regard to it. I told Stanton I thought the course proposed was disrespectful to the President. Stanton said he felt under no obligation to Mr. Lincoln, that the obligations were the other way, both to him and to me. His remarks made an impression on me most unfavorable, and confirmed my previous opinion that he is not faithful and true but insincere.

The real character of J. P. Hale is exhibited in a single transaction. He wrote me an impertinent and dictatorial letter which I received on Wednesday morning, admonishing me not to violate law in the appointment of midshipmen. Learning from my answer that I was making these appointments notwithstanding his warning and protest, he had the superlative meanness to call on Assistant Secretary Fox, and request him, if I was actually making the appointments which he declares to be illegal, to procure on his (Hale’s) application the appointment of a lad for whom he felt an interest. This is after his supercilious letter to me, and one equally supercilious to Fox, which the latter showed me, in which he buttoned up his virtue to the throat and said he would never acquiesce in such a violation of the law. Oh, John P. Hale, how transparent is thy virtue! Long speeches, loud professions, Scriptural quotations, funny anecdotes, vehement denunciations avail not to cover thy nakedness, which is very bald.

The President has issued a proclamation on martial law, — suspension of habeas corpus he terms it, meaning, of course, a suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. Of this proclamation, I knew nothing until I saw it in the papers, and am not sorry that I did not. I question the wisdom or utility of a multiplicity of proclamations striking deep on great questions.

Thursday, 25th—Our knapsacks and tents arrived today by train from Corinth, and it will be more like living now. We have excellent water here, and there are large hotels for invalids, this having been a health resort for Southern people. There are quite a number of mineral springs here, some of sulphur and others of iron.

Thursday, 25th. In the morning went to town and did some chores for the Capt. Made out a requisition and got corn. Helped Chamberlain get some clothing and issue it. Got me a blue overcoat, pants and lariat. Wrote brief letter to Fannie A. In P. M. detachment started for Mt. Vernon. Encamped at “Little York,” 10 miles. Stayed behind with Porter and a few men and drew rations. I couldn’t but notice the difference between the business officers here and at most posts. All pleasant and accommodating. Last night Capt. Nettleton promised me a place in his company as sergeant if I wanted after being mustered out. I was delighted. I should like it well. Overtook the command about an hour after camping. Became quite cold. Frightened a girl—called to inquire our way and surprised them. All seemed frightened.

Thursday, 25th.—Started on after regiment early; walked about four miles and called at house for breakfast; would not take any pay; overtook regiment one and one-half miles west of Paris. Only four of Company F present when stacked arms last night. This gives some idea as to how nearly worn out the whole army was. Started at 10:30 A. M. Passed through Paris 11 A. M. Took Mount Sterling Road; marched six miles and halted on the banks of a beautiful stream and cooked rations. Started at 8 P. M., and marched four miles.

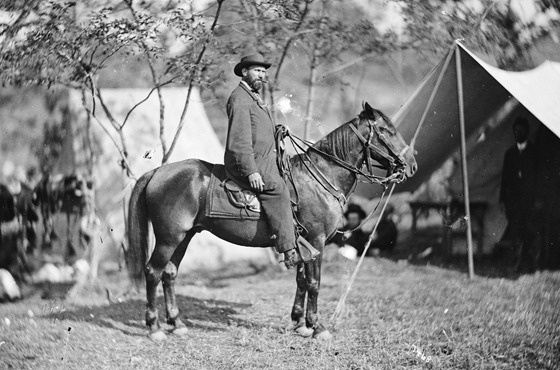

Antietam, Md. Allan Pinkerton (“E. J. Allen”) of the Secret Service on horseback; photograph by Alexander Gardner.

Library of Congress image.

SEPTEMBER 25TH.—Blankets, that used to sell for $6, are now $25 per pair; and sheets are selling for $15 per pair, which might have been had a year ago for $4. Common 4-4 bleached cotton shirting is selling at $1 a yard.

Gen. Lee’s locality and operations, since the battle of Sharpsburg or Shepherdstown, are still enveloped in mystery.

About one hundred of the commissioned officers of Pope’s army, taken prisoners by Jackson, and confined as felons in our prisons, in conformity to the President’s retaliatory order, were yesterday released on parole, in consequence of satisfactory communications from the United States Government, disavowing Pope’s orders, I presume, and stating officially the fact that Pope himself has been relieved from command.

We have taken, and paroled, within the last twelve or fifteen weeks, no less than forty odd thousand prisoners! The United States must owe us some thirty thousand men. This does not look like progress in the work of subjugation.

Horrible! I have seen men just from Manassas, and the battle-field of the 30th August, where, they assure me, hundreds of dead Yankees still lie unburied! They are swollen “as large as cows,” say they, “and are as black as crows.” No one can now undertake to bury them. When the wind blows from that direction, it is said the scent of carrion is distinctly perceptible at the White House in Washington. It is said the enemy are evacuating Alexandria. I do not believe this.

A gentleman (Georgian) to whom I gave a passport to visit the army, taking two substitutes, over forty-five years of age, in place of two sick young men in the hospitals, informs me that he got upon the ground just before the great battle at Sharpsburg commenced. The substitutes were mustered in, and in less than an hour after their arrival, one of them was shot through the hat and hair, but his head was untouched. He says they fought as well as veterans.

September 25.—The One Hundred and Sixty-ninth regiment of New-York volunteers, commanded by Col. Clarence Buel, left Camp Corcoran, at Troy, for the seat of war.— The One Hundred and Fifty-seventh regiment New-York State volunteers,. Col. Philip P. Brown, left Hamilton for Washington City.—The Convention of loyal Governors, at Altoona, Pa., adjourned to meet again in Washington, D. C.

—Sabine Pass, Texas, was this day attacked and captured by the United States steamer Kensington, under the command of Acting Master Crocker, assisted by the mortar-boat Henry Janes, and blockading schooner Rachel Seaman. —See Supplement.

—Judge T. W. Thomas, in the Superior Court, Elbert County, Georgia, in the case of James M. Lovinggood, decided that the rebel conscript act was unconstitutional, and that, therefore, the plaintiff was entitled to his liberty.

24th.—Still no official account of the Sharpsburg fight, and no list .of casualties. The Yankee loss in generals very great—they must have fought desperately. Reno, Mansfield, and Miles were killed; others badly wounded. The Yankee papers say that their loss of “field officers is unaccountable;” and add, that but for the wounding of General Hooker, they would have driven us into the Potomac!

24th.—All quiet this morning. The day is beautiful and bright. I am feeling badly, but as my wound has began to superate, I think I shall be better shortly. I have great confidence in the recuperative power of my constitution, and trust it will be sufficient to eliminate this poison.

We have now had time to look over the late battles and to reflect on the results. We have successfully fought the whole force of the enemy for five days. We drove them at every place, and on the sixth day we permitted them, worn out, discouraged, and out of rations, to depart unmolested. They admitted to our wounded, whose haversacks they robbed, that all they had to eat was what they had taken from our wounded. Gen. McClellan’s aims were satisfied with clearing Maryland of the enemy, when destruction or capitulation should have been demanded. This I do not doubt will be the verdict of history. But how terrible was our loss! Nine Generals fell, killed or wounded, in their determined efforts to vindicate McClellan. All in vain.

We are again on the sea of uncertainty, in relation both to the character of our leaders, and the prospects of the country.