Friday, 26th.—Passed through North Middleton, at 7 A. M. Halted at 3 P. M., two miles from Mount Sterling. Rumored now that we were sent here to intercept Federal General Morgan on his retreat from Cumberland Gap, but Morgan didn’t come this way.

September 2012

Camp near Sharpsburg, Md.,

Friday, September 26, 1862.

Dear Brother and Sister:—

Nothing of interest has occurred since I wrote. We are guarding this ford and “All is quiet along the Potomac” The impression prevails that the rebel army is not far off on the other side of the river, and some morning you may hear of another great battle.

I must answer some of your questions. On the march from the Rappahannock to Manassas, we were surrounded by the rebels most of the time. They got in Pope’s rear at Culpeper and then they kept there, going back between him and Washington as far as Centreville and Fairfax. They followed up in our rear and cut off our supply train, and were continually hovering round our left, waiting an opportunity to attack us. If a fire was kindled, the smoke in the day or the light at night would reveal our position and invite a shell, and we were not allowed to make any. Do you see? But I guess “nobody was hurt.”

You ask what good McClellan accomplished by his campaign on the Peninsula, and add that he has but few friends in your neighborhood. Now I might ask you, what has anyone done on our side towards crushing the rebellion? Is the end of the war apparently any nearer than it was last spring? Have not the rebels a larger army to-day than they had last spring? And are they any less determined to continue the war?

In its leading object, the capture of Richmond, the campaign was a failure. Such men as Greeley instantly pounce upon McClellan and blame him for the fact, when, in my humble judgment, the blame belongs on other shoulders. At Yorktown, he first met the enemy intrenched in one of the strongest positions in the country. When he arrived there, if he had had fresh men, artillery and ammunition, provisions, etc., he might have taken the works by assault, but he had not. His artillery and ammunition trains were stuck in the mud that was almost impassable, and by the time they could be got up, Yorktown was defended by twice our number of troops. Then Greeley and his party sneered because McClellan went to digging. He did dig, and compelled a superior force to evacuate their fortifications. Now, I say, he showed consummate skill in driving them from such a place with scarcely the loss of a single life. He followed the army to their new defenses on the Chickahominy. We all hoped he would take Richmond. We were disappointed, and Greeley sneered again. Of course he blamed McClellan, and thousands who swallow every word the Tribune utters as gospel truth believed him. Well, you ask, if he was not to blame, who was? I blame McDowell. I have hardly patience to call him a general. Great events sometimes spring from slight causes. If you have read the history of the war closely, you will remember the quarrel between McDowell and Sigel, when the latter asked permission to burn a certain bridge to cut off Jackson’s retreat up the Shenandoah, and the refusal of the former.

See the result—the bridge was left unburnt and Jackson crossed in safety and hurled his command of forty thousand on McClellan’s right wing. That sudden reinforcement of the enemy compelled McClellan to withdraw his right wing, leaving the White House unprotected, and consequently, to change his base of operations to the James. His success in doing this won for him the admiration of every military man in this country and Europe. Napoleon said that he who could whip the enemy while he himself retreated, was a better general than one who achieved a victory under the prestige of past success. McClellan retreated fifteen miles and fought the enemy every day for seven days, whipping superior forces every day, winding up with the victory at Malvern Hill. There we learned that he is a general. Those who have seen what he had to contend with have confidence in him, and although his campaign was a failure, we see that the blame rests not on him, but on those who failed him just on the eve of success. Had McDowell allowed Sigel to burn that bridge, Fremont could have come up with him, and uniting his forces with those of McDowell, Sigel and Banks, they could have annihilated Jackson’s army, or at least beaten it so it never could have troubled us, and then following up, united all their force with us and swept on into Richmond. When you wrote, you had not heard of McClellan’s victory at Antietam. If you had, I think you would not have asked the question. Public confidence, led by Greeley, and ever hasty to condemn, was severely shaken when he left the Peninsula. I think he has regained at least a part of it by that hard earned victory. If I were at home nothing would make me ready to fight sooner than to hear some home guard abuse McClellan. I am afraid I should lay myself liable to indictments for assault and battery pretty often, if public opinion is as you say. Don’t swallow every word old Greeley says as the pure truth. A man will do a great deal for party and call it country. McClellan is a Democrat, though not a politician. Fremont is a Republican. Now, see if Greeley don’t join in the popular outcry against McClellan and want Fremont to take his place. Compare what you know of the generalship of the two men, and ask yourself if Greeley’s spirit is party or country.

I got started so about McClellan that I almost forgot the one-fingered mittens and everything else in both letters. I will answer that by informing you that my whole wardrobe consists of what I wear at one time. I have not even one extra pair of socks or a shirt. When I get a chance to wash I hang my shirt up and go without till it gets dry. I should not wonder if another year’s soldiering would enable me to do without clothing altogether, and save my $42 for postage and tobacco money. I suppose Almon thinks his mittens and his oil-cloth fixings “big things,” but I wouldn’t give a snap of the finger for them now. They are very well in winter quarters, but I would not carry them ten miles on a march for them.

I suppose that two thousand soldiers looked as big to you as our regiment did to me when I first enlisted at Erie. I would not consider that much of a crowd now. I can see the camp of ten thousand from where I am writing. The greatest show of troops I have seen was at the review near Washington last fall. Old Abe and Little Mac had eighty thousand there on parade and that was a show. I have seen the most of McClellan’s, McDowell’s, Pope’s, Banks’, and Sigel’s armies, but I would rather see two or three pretty girls and a glee-book this afternoon than the whole of them. Write soon as you can.

From the Twelfth Regiment.

Rendezvous at Brattleboro—First Guard Duty.

In Camp, Brattleboro, Sept. 26, 1862.

Dear Free Press:

This correspondence must begin a little back of the natural starting point of our leaving Burlington. The uppermost thing in my mind, as I write, is a sense of the kindly interest in the Howard Guard,[1] on the part of the citizens of Burlington, shown by the concourse which crowded the Town Hall on Wednesday evening to give emphasis to our sword presentation to our worthy captain; by the kind sentiments expressed and the hearty God bless you’s uttered there and then; and by what seemed to us the turn out en masse of the town of Burlington to see us off the next morning. Those demonstrations touched every man in the Guard, and will not soon be forgotten by them. It was an unfortunate thing for us, that our departure was so hasty as to deprive most of us of the opportunity of giving the final hand-shake to our friends.

Our ride to Brattleboro was a pleasant one. “We were joined at Brandon by the Brandon company, at Rutland by the Rutland company, and at Bellows Falls by the long train with the remainder of the regiment. At every station, the people seemed to be out in multitudes, and from the doors and windows of every farm-house on the way the handkerchiefs were fluttering. These nine months regiments appear to be objects of especial interest on the part of the citizens of Vermont, and I trust they will fulfil the expectations of their friends. I am told that the arrival of a whole regiment, in camp, on the day set, is something unprecedented here.

We reached Brattleboro about half-past four o’clock. The regiment had a dusty march enough to camp, where, after considerable exertion on the part of Col. Blunt, it was finally formed into line, in front of the barracks. The companies are, most of them, deficient in drill, and the men have in fact, about everything to learn. They did, however, finally get into line parallel with the barracks without having the line of buildings moved to correspond with the line of men, which for a time appeared to be the only way in which any kind of parallelism could be established between the two. The companies are composed for the most part, however, of men who will learn quickly, and a few days of steady drill will tell another story. We broke ranks just at dark, received our blankets, woolen and india-rubber, selected our bunks, and marched off to supper, which was abundant and good enough for anybody, sauced as it was with a hearty appetite.

The barracks are houses of plain boards, ten in number, within which wooden bunks are ranged for the men, in double tiers. I cannot speak from experience ,as yet, as to their comfort, your humble servant having been among the fortunate individuals who, constituting the first eight (alphabetically) of the company, were the first detailed for guard duty. This I found to mean a couple of hours of such rest as could be extracted from the soft side of a hemlock plank in the guard house, with sergeants and corporals and “reliefs” coming in and going out, and always in interested conversation when not in active motion; then two hours (from 11 to 1) of pacing a sentry beat, musket on shoulder, over what by this time is a path, but then was an imaginary, and in the darkness, uncertain, line on the dew-soaked grass of the meadow; then about three hours more of that “rest” I have alluded to, but this time I found the plank decidedly softer, and slept in spite of the trifling drawbacks mentioned; then two hours more of sentry duty ; and then—volunteers having been called for for special guard duty—two hours more of the same. By this time it was well into the morning.

On the whole it was quite a night, for the first one in camp. I rather liked it. To be sure, if the only proper business of the night be sleeping, it was not as successful a piece of business in that way as could be conceived of, but I natter myself that it was a successful effort at guard duty. Not a rebel broke in, nor a roving volunteer broke out, over my share of the line, and if there was no sleeping there was a good deal of other things. There was, for instance, a fine opportunity for the study of astronomy; ditto, for meditation. I read in the bright planets success for the good cause, and glory for the Twelfth Vermont, and mused—on what not. This was one of the finest opportunities to see the Connecticut valley mist rise from the river and steal over the meadows, giving a shadowy veil to the trees, a halo apiece to the stars, and adding to the stature of my comrade sentinels till they loomed like Goliaths of Gath through the fog-cloud. There was also the opportunity to see the morning break, not with the grand crash of bright sunrise, but cushioned and shaded by that same fog-bank, till the break was of the softest and most gradual. Who will say that these are not compensations, and who wouldn’t be a soldier?

To-day the regiment is doing nothing but settle itself in its quarters. If it does anything worth telling, I shall try to tell it to you.

B.

[1] The regiment consisted of ten companies of Vermont Militia, reorganized under Pres. Lincoln’s call of August 4, 1862, for 300.000 militia to serve for nine months. The Burlington Company had been known in the State Militia as the Howard Guard. The Company had in its ranks twelve men of collegiate education, and other substantial citizens who had not felt able to leave their business or professions for three years, but were glad to enlist for a shorter term; and the regiment as a whole was largely composed of such citizens.

“The war now swallows up the children and the elders.”–Adams Family Letters, Charles Francis Adams, U.S. Minister to the U.K., to his son, Charles.

London, September 26, 1862

Latterly indeed we have felt a painful anxiety for the safety of Washington itself. For it is very plain that the expedition of the rebels must have been long meditated, and that it embraced a plan of raising the standard of revolt in Maryland as well as Pennsylvania. It has been intimated to me that their emissaries here have given out significant hints of a design to bring in both those states to their combination, which was to be executed about the month of September. That such a scheme was imaginable I should have supposed, until the occurrence of General Pope’s campaign and the effects of it as described in your letter of the 29th ulto….

Thus far it has happened a little fortunately for our comfort here that most of our reverses have been reported during the most dead season of the year, when Parliament was not in session, the Queen and Court and ministry are all away indulging in their customary interval of vacation, and London is said to be wholly empty — the two millions and a half of souls who show themselves counting for nothing in comparison with the hundred thousand magnates that disappear. It is however a fact that the latter make opinion which emanates mainly from the clubhouses. Here the London Times is the great oracle, and through this channel its unworthy and degrading counsels towards America gain their general currency. I am sorry for the manliness of Great Britain when I observe the influence to which it has submitted itself. But there is no help for it now. The die is cast, and whether we gain or we lose our point, alienation for half a century is the inevitable effect between the two countries. The pressure of this conviction always becomes greatest in our moments of adversity. It is therefore lucky that it does not come when the force of the social combination is commonly the greatest also. We have thus been in a great degree free from the necessity of witnessing it in society in any perceptible form. Events are travelling at such a pace that it is scarcely conceivable to suppose some termination or other of this suspense is not approaching. The South cannot uphold its slave system much longer against the gradual and certain undermining of its slaveholding population. Its power of endurance thus far has been beyond all expectation, but there is a term for all things finite, and the evidences of suffering and of exhaustion thicken. The war now swallows up the children and the elders. And when they are drawn away, what becomes of the authority over the servants? It may last a little while from the force of habit, but in the end it cannot fail to be obliterated….

SEPTEMBER 26TH.—The press here have no knowledge of the present locality of Gen. Lee and his army. But a letter was received from Gen. L. at the department yesterday, dated on this side of the Potomac, about eighteen miles above Harper’s Ferry.

It is stated that several hundred prisoners, taken at Sharpsburg, are paroled prisoners captured at Harper’s Ferry. If this be so (and it is said they will be here to-night), I think it probable an example will be made of them. This unpleasant duty may not be avoided by our government.

After losing in killed and wounded, in the battle of Sharpsburg, ten generals, and perhaps twenty thousand men, we hear no more of the advance of the enemy; and Lee seems to be lying perdue, giving them an opportunity to ruminate on the difficulties and dangers of “subjugation.”

I pray we may soon conquer a peace with the North; but then I fear we shall have trouble among ourselves. Certainly there is danger, after the war, that Virginia, and, perhaps, a sufficient number of the States to form a new constitution, will meet in convention and form a new government.

Gen. Stark, of Mississippi, who fell at Sharpsburg, was an acquaintance of mine. His daughters were educated with mine at St. Mary’s Hall, Burlington, N. J.—and were, indeed, under my care. Orphans now!

September 26.—The Fifth and Sixth regulars, with Capt. Robertson’s battery of horse-artillery, went out from Bolivar Heights, Md., on a reconnoissance, under command of Major Whiting of the Second cavalry. At Halltown, five miles off, they encountered the rebel pickets, and drove them in. Approaching within a mile and a half of Charlestown, they met the rebels in force, with infantry, cavalry, and one battery. There was considerable picket-firing, but no casualties on the National side. The expedition, ascertaining that the enemy occupied Charlestown in force, returned, bringing five or six prisoners. Several of them rode horses branded “U. S.,” which they said were captured at the first Bull Run battle.

—The rebel General Bragg issued a proclamation from Bardstown, Ky., addressed to the people of the North-Western States, announcing the motives and purpose of his presence with an army among them. He informed them that the free navigation of the Mississippi River was theirs, and always had been, without striking a blow.

—A skirmish took place near Warrenton Junction, Va., between a reconnoitring force of Union troops, under the command of Col. McLean, and a body of rebel cavalry, resulting in a rout of the latter, leaving in the hands of the Nationals a large quantity of commissary and quartermaster’s stores.

—The Twenty-sixth New-Jersey regiment, one thousand strong, left Newark, N. J., to-day, en route for the seat of war.—The Twenty-third regiment New-Jersey volunteers, Col. Cox, one thousand strong, fully equipped, left Camp Cadwalader this morning, in steamers, for Washington.

—In the rebel House of Representatives majority and minority reports were submitted by the Committee on Foreign Affairs, to whom had been referred certain resolutions relating to the policy of the war, and which recommended to Jeff Davis the issuing of a proclamation offering the free navigation of the Mississippi River and its tributaries, and the opening of the market of the South to the inhabitants of the North-Western States, upon certain terms and conditions.—An unsuccessful attempt to capture the steamer Forest Queen was made at Ashport, Tenn., by a band of rebel guerrillas under Capt Faulkner.— Louisville Journal, September 30.

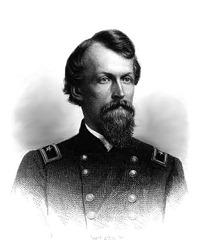

David Bell Birney (May 29, 1825 – October 18, 1864) was a businessman, lawyer, and a Union General in the American Civil War. Birney entered the Union army just after Fort Sumter as lieutenant colonel of the 23rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment, a unit he raised largely at his own expense. Just prior to the war he had been studying military texts in preparation for such a role. (Wikipedia)

25th.—The tables were turned on Saturday, as we succeeded in driving a good many of them into the Potomac. Ten thousand Yankees crossed at Shepherdstown, but unfortunately for them, they found the glorious Stonewall there. A fight ensued at Boteler’s Mill, in which General Jackson totally routed General Pleasanton and his command. The account of the Yankee slaughter is fearful. As they were recrossing the river our cannon was suddenly turned upon them. They were fording. The river is represented as being blocked up with the dead and dying, and crimsoned with blood. Horrible to think of! But why will they have it so? At any time they might stop fighting, and return to their own homes. We do not want their blood, but only to be separated from them as a people, eternally and everlastingly. Mr.—— , Mrs. D., and myself, went to church this evening, and after an address from Mr. K. we took a delightful ride.

A letter from B. H. M., the first she has been able to write for six months, except by “underground railroad,” with every danger of having them read, and perhaps published by the enemy. How, in the still beautiful but much injured Valley, they do rejoice in their freedom! Their captivity—for surrounded as they were by implacable enemies, it is captivity of the most trying kind—has been very oppressive to them. Their cattle, grain, and every thing else, have been taken from them. The gentlemen are actually keeping their horses in their cellars to protect them. Now they are rejoicing in having their own Southern soldiers around them; they are busily engaged nursing the wounded; hospitals are established in Winchester, Berryville, and other places.

Letters from my nephews, W. B. N. and W. N. The first describes the fights of Boonesborough, Sharpsburg, and Shepherdstown. He says the first of these was the severest hand-to-hand cavalry fight of the war. All were terrific. W. speaks of his feelings the day of the surrender of Harper’s Ferry. As they were about to charge the enemy’s intrenchments, he felt as if he were marching into the jaws of death, with, scarcely a hope of escape. The position was very strong, and the charge would be up a tremendous hill over felled timber, which lay thickly upon it—the enemy’s guns, supported by infantry in intrenchments, playing upon them all the while. What was their relief, therefore, to descry the white flag waving from the battlements! He thinks that, in the hands of resolute men, the position would have been impregnable. Thank God, the Yankees thought differently, and surrendered, thus saving many valuable lives, and giving us a grand success. May they ever be thus minded!

“In fact this whole subject of battle is misunderstood at home.”–Adams Family Letters, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., to his mother.

Sharpsburg, Md.

September 25, 1862

Next morning my only good horse was fairly done up and in the name of humanity I had to leave her at Frederick to take my chance of ever seeing her again, and with her, as I could not burden my other horse, I had to leave all my baggage and left everything including my last towel, my tooth-brush, my soap and every shirt and this, alas! was a fortnight ago! As soon as I left her I followed the regiment and had hardly left the town when the sound of artillery in the front admonished me that now we were practically in the advance. I pressed forward and rejoined the column some three miles from the town at a halt and with sharp artillery practice in front. Here we stood three hours resting by the side of the road and waiting for it to be opened for us. Now and then the shot and shell fluttered by us, reminding me of James Island. Some of them came disagreeably near and at last some infantry came up and for a moment sat down to rest with us. I told a Captain near me that the enemy had a perfect range of the road and he’d better be careful how he drew their fire and just as I uttered the words, r-r-r-h went a round shot through the bushes over my head, slid across Forbes and Caspar as they lay on the ground some thirty yards further on and took off the legs of three infantry men next to them. After that it did n’t take long for the infantry to deploy into the field and leave us in undisturbed possession of the road. Still the infantry did it and the enemy soon limbered up and were off, having delayed our pursuit some three hours. Then we followed and pushed over the hills wondering at the strength of the enemies’ position. As we got to the top we pushed on faster and faster until we went down the further side at a gallop. The enemy were close in front and now was the time. Soon we took to the fields and then, on the slope of a hill, with the enemy’s artillery beyond it, formed in column. More shelling, more artillery, and the bullets sung over our heads in lively style, and then “forward” as fast as we could go, over the hill, pulling down fences, floundering through ditches, struggling to outflank them. But the fences were too much for us and we had to return to the road, all losing our tempers and I all my writing materials, the one thing I had clung to. We made the road, however, in time to witness some of the humbug of the war. As we clattered into the town the Illinois cavalry, commanded by Colonel Farnsworth, not unknown to my father, were in front of us and, having hurried into the town were cracking away with their carbines and giving to me, at least, the idea of a sharp engagement in process. We followed them and got our arms all ready, but, as I rode through the single street of the pretty little town, a little excited and pistol in hand, I was somewhat surprised at the number of women who were waving their handkerchiefs, hailing us with delight as liberators and passing out water to our soldiers. For now we were in the truly loyal part of Maryland and everywhere were greeted with delight. It certainly did n’t look to me much like a battle, and yet there were those carbines snapping away like crackers on the 4th of July. In vain I looked for rebels, nary one could I see and at last it dawned on my mind that I was in the midst of a newspaper battle — “a cavalry charge,” “a sharp skirmish,” lots of glory, but n’ary reb.

Here we paused, while I thought we should have pressed forward, and our artillery battered away from the hill to see if any one was there. Meanwhile the rebels burned the bridge before us and made off for the range of hills on the other side of the valley. Presently we followed, forded the stream and followed them up the road, through the most beautiful valley I ever saw, all circled on three sides with lofty wooded ranges surrounding a beautiful rolling valley highly cultivated and blooming like a garden. A blazing bridge and barn in the middle of it suggested something unusual. We hurried through the valley and up the hills on the other side and there we made a pause, brought to a dead stand. It did n’t look like much, but we did n’t like to meddle with it. It was only a single man on horseback in the middle of the road some few hundred yards before us, but it stopped us like a brick wall. We stood on the brow of one hill, with a straight road running through the valley below and disappearing in a high wooded range on the other side. We did n’t know it then, but we were looking on what next day became the battle field of South Mountain. In the road below us were a few rebel videttes and on the hill beyond were posted, hardly to be distinguishable even with our glasses, a battery of artillery. We stood and looked and debated and at last our leaders concluded that it was n’t healthy to go forward, and so we went back. We went into camp on a hill-top and passed a tedious night. It was very cold, and we were hungry, but still we slept well and in the morning feasted on an ox we killed the night before.

At seven o’clock we moved forward to our position of the day before, struggling along to the front through a dense advancing army corps. We got there and took up our position in support of a battery and soon our artillery opened and after about an hour the enemy began to answer. Presently we were moved far to the front and of course a blunder was made, and we found ourselves drawn up in a cornfield in front of our most advanced battery and between it and the enemy, with the shells hurtling over us like mad, and now and then falling around us, but fortunately doing us no harm save ruffling our nerves. Here we sat on our horses for two hours, doing no good and unpleasantly exposed. At last we were moved from there and sent round to our left to support some infantry and there we passed the afternoon, listening to the crackle of musketry and the roar of artillery till night, when it ceased and the men lay down in ranks and slept, holding the bridles of the horses. This was all we saw of the battle of South Mountain, which at the time we supposed to be a heavy skirmish….

Here we lay all that day and I think the next, with a continual spattering of shells around, some of which injured other commands adjoining but all spared ours, and, at last, one day we were ordered early to the rear and we knew there was to be a big fight. Then came the battle of Antietam Creek and we saw about as much of it as of that at South Mountain. We were soon brought hurriedly to the extreme front and posted in support of a battery amid the heaviest shelling and cannonade I ever heard. It was a terrific artillery duel, which lasted where we were all day and injured almost no one. At first, as we took up position, we lost a horse or two, and the storm of artillery, the crashing of shells and the deep reverberations from the hills were confusing and terrifying, and yet, so well were we posted and so accustomed to it did we become, that ten minutes after the imminent danger was over and we were ordered to dismount, I fell sound asleep on the grass and my horse got away from me.

In fact this whole subject of battle is misunderstood at home. We hear of the night before battle. I have seen three of them and have thought I saw half a dozen when the battle did n’t come off, and I have never yet seen one when every officer whom I saw did not seem, not only undisturbed, but wholly to fail to realise that any thing unusual was about to occur. In battle men are always frightened on coming under fire, but they soon get accustomed to it, if it does little execution, however heavy it may be. If the execution is heavy they’re not nearly so apt to go to sleep, and I can’t say I have ever yet fallen in with that lust for danger of which I have read….

25th—Well, Gen. Lee is, safely to himself, out of Maryland, into which he came in the confident expectation of adding at least fifty thousand men to his army, but which he left with fifteen thousand less than he brought in.

My hand is excessively painful, though all constitutional symptoms have left. Suppuration has fairly set in, and I no longer feel any uneasiness as to results.