JULY 2D.—More fighting to-day. The enemy, although their batteries were successfully defended last night at Malvern Hill, abandoned many guns after the charges ceased, and retreated hastily. The grand army of invasion is now some twenty-five miles from the city, and yet the Northern papers claim the victory. They say it was a masterly strategic movement of McClellan, and a premeditated change of base from the Pamunky to the James; and that he will certainly take Richmond in a week and end the rebellion.

Monday, July 2, 2012

Wednesday, 2d—I went out about a half mile from camp to pick blackberries, and I picked a gallon of them and sold them to the hospital steward for $1.25.

Camp Jones, July 2, 1862. Tuesday [Wednesday]. — Rained all night; weather cold. Water must again be abundant. Gradually cleared off about 3 or 4 P. M.

Dispatches state that McClellan has swung his right wing around and pushed his left towards James River, touching the river at Turkey Island, fifteen miles from Richmond. Is this a voluntary change of plan, or is it a movement forced by an attack? These questions find no satisfactory response in the dispatches. Some things look as if we had sustained a reverse. (1.) It is said the move was “necessitated by an attack in great force on Thursday.” (2.) All communication with Washington was cut off for two or three days. (3.) We have had repeated reports that the enemy had turned our right wing. (4.) The singular denial of rumors that our army had sustained a defeat, viz., that “no information received indicated a serious disaster.” (5.) The general mystery about the movement.

It may have been according to a change of plan. I like the new position. If we are there uninjured, with the aid of gunboats and transports on James River, we ought soon to cripple the enemy at Richmond.

2nd. Wednesday. In our saddles at 5 A. M. Marched 8 miles west, near where the Major and we boys captured the wagon. Nothing special occurred.

One of the hospital duties of all the nurses at the front was writing letters home for the sick and wounded men, and sometimes the sad work of telling the story of their last few hours of life. That such letters helped to comfort sorrowful hearts, the following answer to one shows. The soldier was mortally wounded in the seven days’ fight, and in E’s care on the hospital ship.

To Mrs. Joseph Howland.

July 2nd, 1862.

Madam: Your letter of the z6th ultimo, conveying the mournful intelligence of the death of R. P., was received on Monday, the 30th ult. . . .

Until I received your letter, I had indulged the hope he would survive the injury; and had —not ten minutes before it was delivered to me—been informed by a lady, whose son is in the same division, that he was wounded, and that the other members of the company were preparing to send him home. This information, with a knowledge that he was of a robust constitution, and perfectly healthy, induced the belief he would recover. . . .

Madam, that letter of yours, although it was a messenger of death, when it was received by those who were being tortured by alternating thoughts of hope and fear, was like the visit of an angel; for it relieved their minds of a torturing anxiety.

I am requested by R’s father to let you know that he is utterly unable to express his gratitude; that the only way he feels able to compensate you is by offering his heartfelt thanks.

Madam, the occupation which it appears you have chosen, that of alleviating the condition of those who are in affliction, is for its labor paid in a still secret way, which is not fully appreciated by any, except they be like you; for I doubt not, that on receipt of this, (when you will have known that you have been instrumental in conferring a lasting favor,) a lady of your nature will feel she is somewhat repaid.

Fort Barnard, Va., July 2, 1862.

Dear Mother, Sister and Brothers:

It is a cold chilly night and has been all day, for this date. I am crowding as close to the stove as I can sit, in order to keep up animal heat outwardly. I have got acquainted with a farmer’s son about a quarter of a mile from here. The Capt. is well acquainted with the man; he owns a large amount of property around here. The fort is built on his ground. They are a fine family. We go off together Sundays, he having to work other days. He has got two horses under his care; was cutting hay yesterday. As I was going to say, we went off Sunday and visited all the place; he knows all about here and of course knows the girls. I ate supper with them the other night, so you see I am all hunk. Going to get acquainted with some rich young lady, marry and settle down. I suppose you think I am going to work rather early. Well, count it we are Soldiers. Is n’t it a great thing to be a Soldier! We don’t get much war news; expect to hear soon that McClellan is in Richmond. I am going to try to go to a picnic 4th of July. I have finished the muster rolls which I have to make out every two months. Here I must close, or at least try to! Love to all.

Yours truly,

Leverett Bradley, Jr.

P. S. I don’t think much of this letter, but could not think of anything to write.

[On July 11 he had his sixteenth birthday.—Ed.]

2d.—What relief it was, last night, at half-past 9, after the six day’s of excitement, fatigue, fighting and famine, to lie down once more, secure of a good long night’s rest! What a surprise, the whispered call, in just three hours, to rise quietly and resume the march! And what was our astonishment, when daylight revealed to us the fact that we were now retracing the very road by which we had been trying to escape. On discovering this the men began to waver in their confidence. But soon we left this road and bore off “down the river,” and of the scene which now followed, neither Hogarth’s pencil nor Hall’s pen could render the faintest idea. The rain was pouring in such torrents as I never saw the clouds give down. The men at every step, sank nearly to their knees in mud. The officers, either sulky or excited, were driving them to a double-quick, which it was impossible for them to maintain for more than a few rods. They began to fall out, and, in half an hour, every field, and all the open country, as far as the eye could reach, presented the appearance of a moving, hurrying mob. I was here strongly reminded of my school boy imaginations of the Gulf Stream. This swaying, surging mass presenting the idea of the ocean lashed into irregular fury by driving storms, whilst a part of General Smith’s division, moving in unbroken column through the mass, could not but recall the picture of that little stream as from the beginning of time it has preserved its quiet course, in despite of all the convulsions and conflicts of the warring elements. So great was the demoralization at this time, that I have not a doubt that an unexpected volley of either musketry or artillery would have produced a stampede which would have shamed Manassas. I saw no officer so calm, so collected, so perfectly himself as our Division Commander, General Smith. By the teachings which I had received at Camp Griffin, I had been made to believe that he could never be a man for an emergency. At the most trying moment of the day, I bore him a hurried message from two miles away. He saw me coming on the full run, through the heavy rain and mud, and as I rode up he received me with a quiet, pleasant bow of inquiry. I delivered my message, which was important, and involved the fate of his Division, without the least hurry or the slightest hesitation, and in the very fewest words which could make it forcible, as if he had known the object of my coming, and had his answer prepared, he gave me his orders, and calmly resumed his other duties. The prejudices planted and cultured at Camp Griffin were all dissipated.

2d.—What relief it was, last night, at half-past 9, after the six day’s of excitement, fatigue, fighting and famine, to lie down once more, secure of a good long night’s rest! What a surprise, the whispered call, in just three hours, to rise quietly and resume the march! And what was our astonishment, when daylight revealed to us the fact that we were now retracing the very road by which we had been trying to escape. On discovering this the men began to waver in their confidence. But soon we left this road and bore off “down the river,” and of the scene which now followed, neither Hogarth’s pencil nor Hall’s pen could render the faintest idea. The rain was pouring in such torrents as I never saw the clouds give down. The men at every step, sank nearly to their knees in mud. The officers, either sulky or excited, were driving them to a double-quick, which it was impossible for them to maintain for more than a few rods. They began to fall out, and, in half an hour, every field, and all the open country, as far as the eye could reach, presented the appearance of a moving, hurrying mob. I was here strongly reminded of my school boy imaginations of the Gulf Stream. This swaying, surging mass presenting the idea of the ocean lashed into irregular fury by driving storms, whilst a part of General Smith’s division, moving in unbroken column through the mass, could not but recall the picture of that little stream as from the beginning of time it has preserved its quiet course, in despite of all the convulsions and conflicts of the warring elements. So great was the demoralization at this time, that I have not a doubt that an unexpected volley of either musketry or artillery would have produced a stampede which would have shamed Manassas. I saw no officer so calm, so collected, so perfectly himself as our Division Commander, General Smith. By the teachings which I had received at Camp Griffin, I had been made to believe that he could never be a man for an emergency. At the most trying moment of the day, I bore him a hurried message from two miles away. He saw me coming on the full run, through the heavy rain and mud, and as I rode up he received me with a quiet, pleasant bow of inquiry. I delivered my message, which was important, and involved the fate of his Division, without the least hurry or the slightest hesitation, and in the very fewest words which could make it forcible, as if he had known the object of my coming, and had his answer prepared, he gave me his orders, and calmly resumed his other duties. The prejudices planted and cultured at Camp Griffin were all dissipated.

I did see him, however, once during the day, a little excited. We were hard pressed by the enemy on all sides of us. We had repulsed him in every fight, protecting our immense train of wagons, now seventy miles long. But so critical had become our situation that it was decided that to save the army it was necessary to abandon the transportation; Gen. Smith rode along the line of his own transportation, clearing the road of the wagons that the rear guard of infantry and artillery might pass. He once or twice ordered a teamster out of the road. The man did not obey. ‘Twas no time to arrest him; he grappled him by the neck, and for half a minute kept him in that peculiar state of gyration which a hungry soldier often communicates to the body of a rebel rooster about midnight. He had no more trouble with that teamster. But the confusion of those teams! I thought Mons. Violet in his stampede of buffaloes had got up a description of confusion which no reality could ever approach. I had formed vague ideas of Bedlam, of Pandemonium; but a million of buffaloes on a stampede, Bedlam turned loose, and Pandemonium “on a bust,” all mixed and mingled, could form no approximation to a train of teams, seventy miles long, on a “skedaddle.”

But all day the rain poured in torrents; men dropped by the wayside and were left. Some died from exposure; some dragged themselves into camp, and many were captured by the enemy. The night of the seventh day has come. The question of capitulation has been heard in whispers all day. But now that we are once more in camp, and in a position to offer or accept battle, most of the men scoff at the idea of capitulation, and say “fight it out.” Nearly all the men, in the retreat, have thrown away their knapsacks and blankets, and have thrown themselves down in their wet clothes, and in mud and water which nearly covers them, hoping to get a little rest after the incessant fatigues of the week. The wind blows damp and chilly, and I fear the poor fellows are to have a hard night of it.

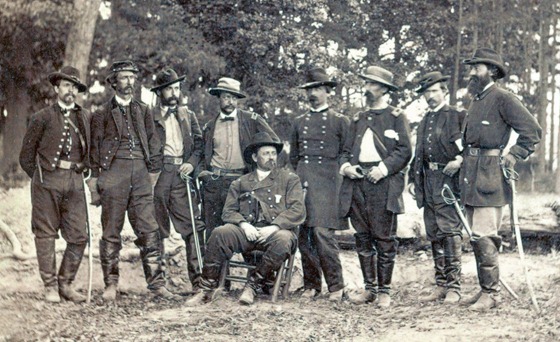

From Library of Congress:

Summary: Stereograph showing Major General William Farrar Smith seated in center of a group of Union officers near Malvern Hill, Virginia.

by a Mathew Brady photographer.

Part of Civil War Photograph Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Record page for this image: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011661059/

From midnight, until 4 A. M., the movement of troops continued; till at last we were the only brigade left on the field. General French finally concluded his brigade had been forgotten, through somebody’s negligence, and reluctantly gave the order to fall in and follow the crowd. We stepped out, and soon overtook the retiring column, which was spread out on either side of the road, marching without much order and apparently indifferent to discipline. It rained a little during the night, and about daylight poured down in torrents, turning the roads into streams, and fields into sticky mud, making the marching execrable. Many of the batteries were obliged to double their teams on the guns, at certain places on the road, and only succeeded in getting them along by the greatest exertion. In the course of the day we passed several guns deserted in the road, and later on a siege battery, which effectually blockaded the route. The ground was slippery, the men fatigued, and everybody disgusted, which must have accounted for the great disorder. It really began to look like another Bull Run, and when a detachment of pioneers came up the road, and began felling trees across it, directly in front of the moving train of wagons, and artillery, we concluded some one must have gone crazy, and in sheer despair gave up thinking at all. When the battery commanders expostulated with the pioneer officer, he said he had his orders from the chief of staff of the army, and must obey them. The result was all the wagons and guns in rear of the obstructions, had to be hauled up the side of the road, and move in the fields, which was an immense and unnecessary labor. Our brigade marched in the fields in good order, without instructions till 4 P. M., when one of Sumner’s staff came along, and was surprised to learn we had been forgotten. He told us we were bound for Harrison’s Landing, where the army would remain and entrench itself. That Turkey bend, the position about Malvern Hill, was considered too weak to hold. The river was too narrow for the operations of the gunboats, and there was no natural protection on our right flank. Consequently, Harrison’s Landing had been selected as an ideal position. It seems the general commanding never thought of following up his success, which is the most curious thing, as almost every one else belonging to the army thought it a matter of course. Very shortly after the interview with this staff officer, we were directed to file off into a piece of shrub oak, and there pitch our tents for the night, until the storm subsided. The men were covered from head to foot with mud and made a miserable appearance. The army of Flanders was noted for its swearing, but I should like to back this army, on this particular occasion, against it, and give odds to boot.

Everything was disagreeable; the ground low and almost covered with water, the bushy trees dripping from every leaf and branch and the men thoroughly soaked to their waist in water. It was nearly eight o’clock before the brigade was wholly under cover, and resting from its efforts of the past six days.

July 2.—The army of the Potomac, under the command of General McClellan, in their retreat from before Richmond, this day reached Harrison’s Bar, on the James River, Va.—President Lincoln approved and signed the Pacific Railroad and internal tax bills.

—A Scouting party of Union troops proceeded from Catlett’s Station to Warrenton, Va., and on reaching that place found it occupied by five hundred rebel cavalry.

—Governor Morgan, of New-York, issued a proclamation calling upon the citizens of the State for their quota of troops, to serve for three years or during the war, under the call of the President for three hundred thousand men.—At Clarendon, Ark., a party of Texas cavalry succeeded in capturing three men and six horses belonging to the National force near that place.