JULY 8TH.—Glorious Col. Morgan has dashed into Kentucky, whipped everything before him, and got off unharmed. He had but little over a thousand men, and captured that number of prisoners. Kentucky will rise in a few weeks.

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Tuesday, 8th—The rebels in this locality are not making much of an effort to retake Corinth. The report in camp is that they have sent the greater part of their forces east to reinforce their army in and around Richmond. News came this evening that General McClellan has been whipped and is now retreating from Richmond.

Camp Jones, July 8, 1862. Tuesday. — A fine breezy day on this mountain top. Bathed three miles from here in Glade Creek. I find this sitting still or advancing age (good joke!) is getting me into old gentlemen’s habits. My breath is shorter than it used to be; I get tired easier and the like.

Very little additional from Richmond, but that little is encouraging. Our forces have not, I think, been discouraged or in any degree lost confidence, by reason of anything that has occurred before Richmond. Our losses are not greater than the enemy’s — probably not so great. The Rebel reports here are that our loss is thirty-eight thousand killed and wounded and two thousand prisoners; that they left fourteen thousand dead on the field! This is all wild guessing; but it indicates dreadful and probably nearly equal losses on both sides.

8th. Reveille a little before two. Got coffee and meat for breakfast. Started on the march, in the rear, at daybreak. Like Capt. Smith some better but I long for Major Purington to come back again. Second Brigade in the rear of the first ones. Issued rations.

“Wilson Small,” July 8.

Dear Mother, — For the last two hours I have been watching President Lincoln and General McClellan as they sat together, in earnest conversation, on the deck of a steamer close to us. I am thankful, I am happy, that the President has come, — has sprung across that dreadful intervening Washington, and come to see and hear and judge for his own wise and noble self.

While we were at dinner some one said, chancing to look through a window: “Why, there’s the President!” and he proved to be just arriving on the “Ariel,” at the end of the wharf close to which we are anchored. I stationed myself at once to watch for the coming of McClellan. The President stood on deck with a glass, with which, after a time, he inspected our boat, waving his handkerchief to us. My eyes and soul were in the direction of general headquarters, over where the great balloon was slowly descending. Presently a line of horsemen came over the brow of the hill through the trees, and first emerged a firm-set figure on a brown horse, and after him the staff and body-guard. As soon as the General reached the head of the wharf he sprang from his horse, and in an instant every man was afoot and motionless. McClellan walked quickly along the thousand-foot pier, a major-general beside him, and six officers following. He was the shortest man, of course, by which I distinguished him as the little group stepped on to the pier. When he reached the “Ariel,” he ran quickly up to the after-deck, where the President met him and grasped his hand. I could not distinguish the play of his features, though my eyes still ache with the effort to do so. He is stouter than I expected, but quicker, and more leste. He wore the ordinary blue coat and shoulder-straps; the coat, fastened only at the throat, and blowing back as he walked, gave to sight a gray flannel shirt and a — suspender!

They sat down together, apparently with a map between them, to which McClellan pointed from time to time with the end of his cigar. We watched the earnest conversation which went on, and which lasted till 6 P. M.; then they rose and walked side by side ashore,— the President, in a shiny black coat and stovepipe hat, a whole head and shoulders taller, as it seemed to me, than the General. Mr. Lincoln mounted a led horse of the General’s, and together they rode off, the staff following, the dragoons presenting arms and then wheeling round to follow, their sabres gleaming in the sunlight. And so they have passed over the brow of the hill, and I have come to tell you about it. The cannon are firing salutes, — a sound of strange peacefulness to us, after the angry, irregular boomings and the sharp scream of the shells to which we are accustomed.

All day we have had the little “Monitor” and the ugly “Galena” (flag-ship) and the “Maritanza” beside us, a stone’s throw off. Last evening Commodore John Rodgers, at present commanding on the James, came to see us, and rowed us up the river and round the “Monitor” and his own vessel, the “Galena.” Ugly as she is, I must confess the latter has the most fighting look of anything that I have seen connected with war; she reminds me of Rab in a dog-fight. But they say she is a failure, and a downright fraud upon the Government. She looks something like a Chinese junk, broad at the water-line, and running in from that. She has two large lumps on one side, caused by shots that have passed through her and lodged in the iron casing on the other side.

There is a funny little Rebel gunboat close beside us, captured on Friday by the “Maritanza.” A shell exploded in her boiler, tearing out her intestines, as it were, and doubling her up into the drollest little object. The “Teaser” they call her. The prettiest sight I see is the signalling,—flags by day, and lamps by night; the most incomprehensible, graceful thing that can be seen. The “Galena,” the “Monitor,” and the “Maritanza,” which went off this morning to prevent General Longstreet with twenty thousand men from attempting to cross the river, are just coming in to their evening anchorage, and beginning the pretty signals, which are being answered from the roof of the Harrison House.

Things are not as gloomy here as you fear. The tone and temper of the army are magnificent. If reinforcements are sent, all will be well. Everything depends on the Administration at this moment, — not on the army; that is now made up of veterans, and knows and rejoices in its strength.

Commodore Rodgers has just been to invite us on board his ship. We have accepted for nine o’clock to-morrow morning, though it is a chance if she is not on duty at that and every other hour. He offered also to take us over the “Monitor.” After that — having seen the “Monitor ” and McClellan — I wish to go home. There is no more work for a woman here. The Government is doing well by the sick and wounded. The Sanitary Commission may justly claim that it has led the Government to this; and it can now return to its legitimate supplemental work, — inspecting the condition of the camps and regiments, and continuing on a large scale its supply business. But as for us, we ought to go; to stay here doing nothing, is a sarcasm on the work we have already done.

Sarah Woolsey to Eliza Woolsey Howland

New Haven, Tuesday Night.

I am just home from a very hot day at the New Haven Hospital, and so glad to find Jane’s note with the news of your arrival that I must write a line before going to bed to tell you of it. And thus our week of suspense ends, and while so many thousands are straining eyes and hearts towards the bloody Peninsula, we may draw a long breath and refresh our thoughts with a picture of our dear Joe safe and resting his “honorable scars” amid friends and comfort and home and peace. . . . Do you know that one of our hospital cases here, on seeing your carte de visite the other day, recognized you as the “lady who gave him some very nice wine as he lay on a stretcher at White House, and bowls full of bread and milk afterward “—upon which he quite took on over it. He is one of the “Ten thousand soldier hearts in Northern climes,”

. . . Dr. Frank Bacon is here, having come up on a twenty-day furlough to recruit himself. I have not seen him but hear that he looks wretchedly—utterly broken down by overwork.

The James Island fight occurred early in June, ’62, and in the official report of the general commanding, F. B.’s regiment is singled out for mention: ” The 7th Connecticut moved up in a beautiful and sustained line.” “The 7th Connecticut had been on very severe fatigue duty for three days and three nights.” “The 7th Connecticut advanced in the open field under continued shower of grape and canister.” “The medical officers were unwearied on the battlefield and in the hospital.”

After this service F. B. went home on sick leave. Later he resigned from the 7th Connecticut, passed the examination for the Corps of Surgeons of Volunteers, and was assigned to duty in charge of the Harper’s Ferry Hospital.

Here he found a large accumulation of army supplies and a hospital in what he considered an exposed position. On reporting this to Washington and recommending its breaking up, he received prompt orders to carry out his own views, and had the satisfaction of getting the patients and supplies safely off on the last train, before a rebel dash captured the place. He writes to J. S. W. that if he had continued the hospital at Harper’s Ferry he should have wanted a select party of ministering angels, and asks whether we write M.A. after our names now, ” after the manner of a mature female in the Harper’s Ferry laundry, who sent up a requisition with ‘D. R.’ after her signature, and on a demand for explanation said daughter of the regiment, sir, which I have been adopted by the 109th.’ ”

F. B. was then assigned to duty in Washington on General Casey’s staff, to examine outlying camp hospitals and break them up when expedient, and to overhaul new regiments and their doctors as they came in. Here, a little later, having got permission to join the troops at the front, he had the miserable experience of marching in from the second battle of Bull Run with the Army of the Potomac, defeated again on their old first field.

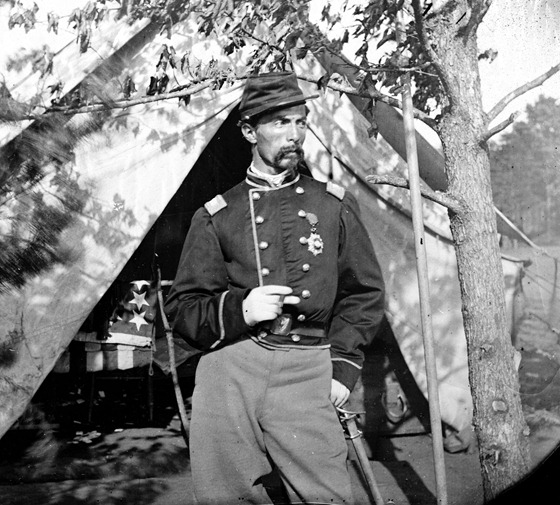

Photo taken by Timothy H. O’Sullivan in the vicinity of Bull Run, July 1862.

From Wikipedia:

Alfred Napoléon Alexander Duffié (May 18, 1833 – November 8, 1880) was a French-American soldier and diplomat who served in the Crimean War and the American Civil War.

When the American Civil War broke out, Duffié enlisted in the Union Army. He first joined the 2nd New York Cavalry (also known as the Harris Light Cavalry), on August 9, 1861, and was soon promoted to the rank of captain. The somewhat quarrelsome Duffié was placed under arrest several times for confrontations with other officers; in one incident, he challenged General Fitz John Porter to a duel. In July 1862 Duffié was appointed to command the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry, with the rank of colonel, by that state’s governor, William Sprague IV. Though the 1st Rhode Island’s officers initially refused to serve under a foreign-born leader, Duffié soon won them over and reorganized the 1st into a fine fighting unit. Assigned to the command of General William Averell, they saw action against Confederate troops under Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson in August 1862, in fighting near Cedar Mountain, Virginia.

From Library of Congress:

One of two images of Duffié in the Library of Congress online catalog.

One of two images of Duffié in the Library of Congress online catalog.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Record pages for images: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003005510/PP/ and http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003005564/PP/

Tuesday, July 8, 1862.—We start to-morrow. Packing the trunks was a problem. Annie and I are allowed one large trunk apiece, the gentlemen a smaller one each, and we a light carpet-sack apiece for toilet articles. I arrived with six trunks and leave with one! We went over everything carefully twice, rejecting, trying to shake off the bonds of custom and get down to primitive needs. At last we made a judicious selection. Everything old or worn was left; everything merely ornamental, except good lace, which was light. Gossamer evening dresses were all left. I calculated on taking two or three books that would bear the most reading if we were again shut up where none could be had, and so, of course, took Shakspere first. Here I was interrupted to go and pay a farewell visit, and when we returned Max had packed and nailed the cases of books to be left. Chance thus limited my choice to those that happened to be in my room—”Paradise Lost,” the “Arabian Nights,” a volume of Macaulay’s History that I was reading, and my prayer-book. To-day the provisions for the trip were cooked: the last of the flour was made into large loaves of bread; a ham and several dozen eggs were boiled; the few chickens that have survived the overflow were fried; the last of the coffee was parched and ground; and the modicum of the tea was well corked up. Our friends across the lake added a jar of butter and two of preserves. H. rode off to X. after dinner to conclude some business there, and I sat down before a table to tie bundles of things to be left. The sunset glowed and faded and the quiet evening came on calm and starry. I sat by the window till evening deepened into night, and as the moon rose I still looked a reluctant farewell to the lovely lake and the grand woods, till the sound of H.’s horse at the gate broke the spell.

![]()

______

Note: To protect Mrs. Miller’s job as a teacher in New Orleans, the diary was published anonymously, edited by G. W. Cable, names were changed and initials were often used instead of full names — and even the initials differed from the real person’s initials.July 8th.—Gunboat captured on the Santee. So much the worse for us. We do not want any more prisoners, and next time they will send a fleet of boats, if one will not do. The Governor sent me Mr. Chesnut’s telegram with a note saying, “I regret the telegram does not come up to what we had hoped might be as to the entire destruction of McClellan’s army. I think, however, the strength of the war with its ferocity may now be considered as broken.”

Table-talk to-day: This war was undertaken by us to shake off the yoke of foreign invaders. So we consider our cause righteous. The Yankees, since the war has begun, have discovered it is to free the slaves that they are fighting. So their cause is noble. They also expect to make the war pay. Yankees do not undertake anything that does not pay. They think we belong to them. We have been good milk cows—milked by the tariff, or skimmed. We let them have all of our hard earnings. We bear the ban of slavery; they get the money. Cotton pays everybody who handles it, sells it, manufactures it, but rarely pays the man who grows it. Second hand the Yankees received the wages of slavery. They grew rich. We grew poor. The receiver is as bad as the thief. That applies to us, too, for we received the savages they stole from Africa and brought to us in their slave-ships. As with the Egyptians, so it shall be with us: if they let us go, it must be across a Red Sea—but one made red by blood.

July 8.—A large and enthusiastic meeting was held in New-Haven, Ct, in response to the call of President Lincoln for volunteers. Speeches were made by Senator Dixon, Governor Buckingham, Rev. Dr. Bacon, A. P. Hyde, T. H. Bond, Rev. Dr. Nadal, G. F. Trumbull, C. Chapman, Capt. Hunt, and others. Commodore Andrew H. Foote presided over the meeting.

—Gen. Shepley, Military Commandant of New Orleans, this day issued an order extending the time in which those who had been in the “military service of the confederate States” could take the parole to the tenth instant.—Gen. Butler issued an order authorizing several regiments of volunteers for the United States army to be recruited, and organized in the State of Louisiana.

—A reconnoissance by the First Maine cavalry was this day made as far as Waterloo, on the Rappahannock River, Va.—A band of rebel guerrillas visited the residence of a Unionist named Pratt, in Lewis County, Mo., and murdered him.

—John Ross, principal Chief of the Cherokee Indians, addressed a letter to Colonel Weer, commanding United States forces at Leavenworth, Kansas, informing him that on the seventh day of October, 1861, the Cherokee Nation had entered into a treaty with “the confederate States.” —(Doc. 147.)

—President Lincoln arrived at Harrison’s Landing, on the James River, Va., and, accompanied by Gen. McClellan, reviewed the army of the Potomac.—Governors Salomon of Wisconsin, and Olden of New-Jersey, issued proclamations calling upon the citizens of their States for their quota of troops, under the call of the President for three hundred thousand men.

—The letters from Gen. McClellan to the War Department, concerning the occupation of Gen. Lee’s residence at White House, Va., were this day laid before Congress.—The removal of Secretary Stanton from the War Department was suggested in various portions of the country.